Periodontal disease, also known as gum disease, is a set of inflammatory conditions affecting the tissues surrounding the teeth. In its early stage, called gingivitis, the gums become swollen and red and may bleed. It is considered the main cause of tooth loss for adults worldwide. In its more serious form, called periodontitis, the gums can pull away from the tooth, bone can be lost, and the teeth may loosen or fall out. Bad breath may also occur.

In dentistry, calculus or tartar is a form of hardened dental plaque. It is caused by precipitation of minerals from saliva and gingival crevicular fluid (GCF) in plaque on the teeth. This process of precipitation kills the bacterial cells within dental plaque, but the rough and hardened surface that is formed provides an ideal surface for further plaque formation. This leads to calculus buildup, which compromises the health of the gingiva (gums). Calculus can form both along the gumline, where it is referred to as supragingival, and within the narrow sulcus that exists between the teeth and the gingiva, where it is referred to as subgingival.

Toothache, also known as dental pain, is pain in the teeth or their supporting structures, caused by dental diseases or pain referred to the teeth by non-dental diseases. When severe it may impact sleep, eating, and other daily activities.

A dental explorer or sickle probe is an instrument in dentistry commonly used in the dental armamentarium. A sharp point at the end of the explorer is used to enhance tactile sensation.

Periodontology or periodontics is the specialty of dentistry that studies supporting structures of teeth, as well as diseases and conditions that affect them. The supporting tissues are known as the periodontium, which includes the gingiva (gums), alveolar bone, cementum, and the periodontal ligament. A periodontist is a dentist that specializes in the prevention, diagnosis and treatment of periodontal disease and in the placement of dental implants.

Veterinary dentistry is the field of dentistry applied to the care of animals. It is the art and science of prevention, diagnosis, and treatment of conditions, diseases, and disorders of the oral cavity, the maxillofacial region, and its associated structures as it relates to animals.

Dental instruments are tools that dental professionals use to provide dental treatment. They include tools to examine, manipulate, treat, restore, and remove teeth and surrounding oral structures.

A dental auxiliary is any oral health practitioner other than a dentist & dental hygienist, including the supporting team assisting in dental treatment. They include dental assistants, dental therapists and oral health therapists, dental technologists, and orthodontic auxiliaries. The role of dental auxiliaries is usually set out in regional dental regulations, defining the treatment that can be performed.

The gingival sulcus is an area of potential space between a tooth and the surrounding gingival tissue and is lined by sulcular epithelium. The depth of the sulcus is bounded by two entities: apically by the gingival fibers of the connective tissue attachment and coronally by the free gingival margin. A healthy sulcular depth is three millimeters or less, which is readily self-cleansable with a properly used toothbrush or the supplemental use of other oral hygiene aids.

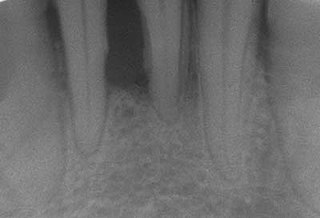

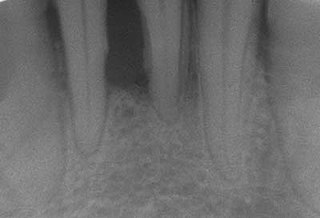

Dental radiographs, commonly known as X-rays, are radiographs used to diagnose hidden dental structures, malignant or benign masses, bone loss, and cavities.

Scaling and root planing, also known as conventional periodontal therapy, non-surgical periodontal therapy or deep cleaning, is a procedure involving removal of dental plaque and calculus and then smoothing, or planing, of the (exposed) surfaces of the roots, removing cementum or dentine that is impregnated with calculus, toxins, or microorganisms, the agents that cause inflammation. It is a part of non-surgical periodontal therapy. This helps to establish a periodontium that is in remission of periodontal disease. Periodontal scalers and periodontal curettes are some of the tools involved.

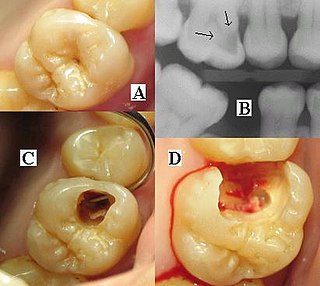

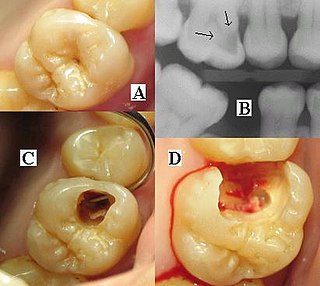

Root canal treatment is a treatment sequence for the infected pulp of a tooth which is intended to result in the elimination of infection and the protection of the decontaminated tooth from future microbial invasion. Root canals, and their associated pulp chamber, are the physical hollows within a tooth that are naturally inhabited by nerve tissue, blood vessels and other cellular entities. Together, these items constitute the dental pulp.

The periodontal curette is a type of hand-activated instrument used in dentistry and dental hygiene for the purpose of scaling and root planing. The periodontal curette is considered a treatment instrument and is classified into two main categories: universal curettes and Gracey curettes. Periodontal curettes have one face, one or two cutting edges and a rounded back and rounded toe. They are typically the instrument of choice for subgingival calculus removal.

Tooth polishing is done to smooth the surfaces of teeth and restorations. The purpose of polishing is to remove extrinsic stains, remove dental plaque accumulation, increase aesthetics and to reduce corrosion of metallic restorations. Tooth polishing has little therapeutic value and is usually done as a cosmetic procedure after debridement and before fluoride application. Common practice is to use a prophy cup—a small motorized rubber cup—along with an abrasive polishing compound.

In dentistry, debridement refers to the removal by dental cleaning of accumulations of plaque and calculus (tartar) in order to maintain dental health. Debridement may be performed using ultrasonic instruments, which fracture the calculus, thereby facilitating its removal, as well as hand tools, including periodontal scaler and curettes, or through the use of chemicals such as hydrogen peroxide.

A periodontal abscess, is a localized collection of pus within the tissues of the periodontium. It is a type of dental abscess. A periodontal abscess occurs alongside a tooth, and is different from the more common periapical abscess, which represents the spread of infection from a dead tooth. To reflect this, sometimes the term "lateral (periodontal) abscess" is used. In contrast to a periapical abscess, periodontal abscesses are usually associated with a vital (living) tooth. Abscesses of the periodontium are acute bacterial infections classified primarily by location.

A phoenix abscess is an acute exacerbation of a chronic periapical lesion. It is a dental abscess that can occur immediately following root canal treatment. Another cause is due to untreated necrotic pulp. It is also the result of inadequate debridement during the endodontic procedure. Risk of occurrence of a phoenix abscess is minimised by correct identification and instrumentation of the entire root canal, ensuring no missed anatomy.

Chronic periodontitis is one of the seven categories of periodontitis as defined by the American Academy of Periodontology 1999 classification system. Chronic periodontitis is a common disease of the oral cavity consisting of chronic inflammation of the periodontal tissues that is caused by the accumulation of profuse amounts of dental plaque. Periodontitis initially begins as gingivitis and can progress onto chronic and subsequent aggressive periodontitis according to the 1999 classification.

Peri-implant mucositis is defined as an inflammatory lesion of the peri-implant mucosa in the absence of continuing marginal bone loss.

Periodontal surgery is a form of dental surgery that prevents or corrects anatomical, traumatic, developmental, or plaque-induced defects in the bone, gingiva, or alveolar mucosa. The objectives of this surgery include accessibility of instruments to root surface, elimination of inflammation, creation of an oral environment for plaque control, periodontal diseases control, oral hygiene maintenance, maintain proper embrasure space, address gingiva-alveolar mucosa problems, and esthetic improvement. The surgical procedures include crown lengthening, frenectomy, and mucogingival flap surgery.