Chaldea was a small country that existed between the late 10th or early 9th and mid-6th centuries BC, after which the country and its people were absorbed and assimilated into the indigenous population of Babylonia. Semitic-speaking, it was located in the marshy land of the far southeastern corner of Mesopotamia and briefly came to rule Babylon. The Hebrew Bible uses the term כשדים (Kaśdim) and this is translated as Chaldaeans in the Greek Old Testament, although there is some dispute as to whether Kasdim in fact means Chaldean or refers to the south Mesopotamian Kaldu.

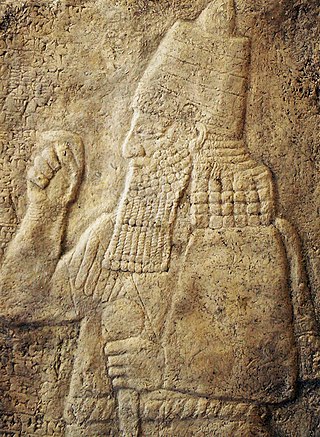

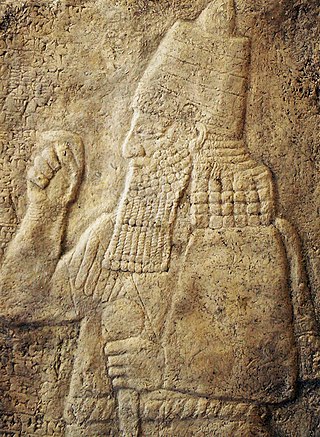

Sennacherib was the king of the Neo-Assyrian Empire from the death of his father Sargon II in 705 BC to his own death in 681 BC. The second king of the Sargonid dynasty, Sennacherib is one of the most famous Assyrian kings for the role he plays in the Hebrew Bible, which describes his campaign in the Levant. Other events of his reign include his destruction of the city of Babylon in 689 BC and his renovation and expansion of the last great Assyrian capital, Nineveh.

Babylonia was an ancient Akkadian-speaking state and cultural area based in the city of Babylon in central-southern Mesopotamia. It emerged as an Akkadian populated but Amorite-ruled state c. 1894 BC. During the reign of Hammurabi and afterwards, Babylonia was retrospectively called "the country of Akkad", a deliberate archaism in reference to the previous glory of the Akkadian Empire. It was often involved in rivalry with the older ethno-linguistically related state of Assyria in the north of Mesopotamia and Elam to the east in Ancient Iran. Babylonia briefly became the major power in the region after Hammurabi created a short-lived empire, succeeding the earlier Akkadian Empire, Third Dynasty of Ur, and Old Assyrian Empire. The Babylonian Empire rapidly fell apart after the death of Hammurabi and reverted to a small kingdom centered around the city of Babylon.

Tiglath-Pileser III, was the king of the Neo-Assyrian Empire from 745 BC to his death in 727. One of the most prominent and historically significant Assyrian kings, Tiglath-Pileser ended a period of Assyrian stagnation, introduced numerous political and military reforms and more than doubled the lands under Assyrian control. Because of the massive expansion and centralization of Assyrian territory and establishment of a standing army, some researchers consider Tiglath-Pileser's reign to mark the true transition of Assyria into an empire. The reforms and methods of control introduced under Tiglath-Pileser laid the groundwork for policies enacted not only by later Assyrian kings but also by later empires for millennia after his death.

Nabopolassar was the founder and first king of the Neo-Babylonian Empire, ruling from his coronation as king of Babylon in 626 BC to his death in 605 BC. Though initially only aimed at restoring and securing the independence of Babylonia, Nabopolassar's uprising against the Neo-Assyrian Empire, which had ruled Babylonia for more than a century, eventually led to the complete destruction of the Assyrian Empire and the rise of the Neo-Babylonian Empire in its place.

Sîn-šar-iškun was the penultimate king of Assyria, reigning from the death of his brother and predecessor Aššur-etil-ilāni in 627 BC to his own death at the Fall of Nineveh in 612 BC.

The Arameans, or Aramaeans, were an ancient Semitic-speaking people in the Near East that was first recorded in historical sources from the late 12th century BC. The Aramean homeland, sometimes known as the land of Aram, encompassed central regions of modern Syria.

Aram was a historical region mentioned in early cuneiforms and in the Bible, populated by Arameans. The area did not develop into a larger empire but consisted of a number of small states in present-day Syria and northern Israel. Some of the states are mentioned in the Old Testament, Damascus being the most outstanding one, which came to encompass most of Syria. Furthermore, Aram-Damascus is commonly referred to as simply Aram in the Old Testament.

The Neo-Babylonian Empire or Second Babylonian Empire, historically known as the Chaldean Empire, was the last polity ruled by monarchs native to Mesopotamia. Beginning with the coronation of Nabopolassar as the King of Babylon in 626 BC and being firmly established through the fall of the Neo-Assyrian Empire in 612 BC, the Neo-Babylonian Empire was conquered by the Achaemenid Persian Empire in 539 BC, marking the collapse of the Chaldean dynasty less than a century after its founding.

The Chaldean dynasty, also known as the Neo-Babylonian dynasty and enumerated as Dynasty X of Babylon, was the ruling dynasty of the Neo-Babylonian Empire, ruling as kings of Babylon from the ascent of Nabopolassar in 626 BC to the fall of Babylon in 539 BC. The dynasty, as connected to Nabopolassar through descent, was deposed in 560 BC by the Aramean official Neriglissar, though he was connected to the Chaldean kings through marriage and his son and successor, Labashi-Marduk, might have reintroduced the bloodline to the throne. The final Neo-Babylonian king, Nabonidus, was genealogically unconnected to the previous kings, but might, like Neriglissar, also have been connected to the dynasty through marriage.

The history of the Assyrians encompasses nearly five millennia, covering the history of the ancient Mesopotamian civilization of Assyria, including its territory, culture and people, as well as the later history of the Assyrian people after the fall of the Neo-Assyrian Empire in 609 BC. For purposes of historiography, ancient Assyrian history is often divided by modern researchers, based on political events and gradual changes in language, into the Early Assyrian, Old Assyrian, Middle Assyrian, Neo-Assyrian and post-imperial periods., Sassanid era Asoristan from 240 AD until 637 AD and the post Islamic Conquest period until the present day.

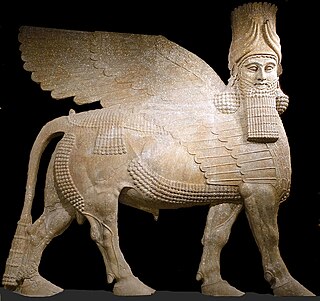

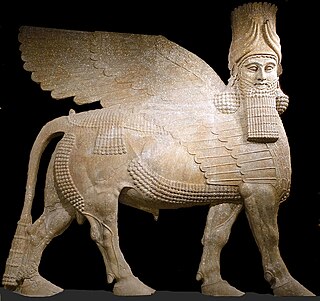

The Neo-Assyrian Empire was the fourth and penultimate stage of ancient Assyrian history. Beginning with the accession of Adad-nirari II in 911 BC, the Neo-Assyrian Empire grew to dominate the ancient Near East throughout much of the 8th and 7th centuries BC, becoming the largest empire in history up to that point. Because of its geopolitical dominance and ideology based in world domination, the Neo-Assyrian Empire is by many researchers regarded to have been the first world empire in history. It influenced other empires of the ancient world culturally, governmentally, and militarily, including the Babylonians, the Achaemenids, and the Seleucids. At its height, the empire was the strongest military power in the world and ruled over all of Mesopotamia, the Levant and Egypt, as well as parts of Anatolia, Arabia and modern-day Iran and Armenia.

The Assyrian conquest of Aram concerns the series of conquests of largely Aramean, Phoenician, Sutean and Neo-Hittite states in the Levant by the Neo-Assyrian Empire. This region was known as Eber-Nari and Aram during the Middle Assyrian Empire and the Neo-Assyrian Empire.

Assyrian continuity is the study of continuity between the modern Assyrian people, a Semitic indigenous ethnic, religious and linguistic minority in the Middle East, and the people of ancient Assyria and Mesopotamia generally. Assyrian continuity is a key part of the identity of the modern Assyrian people. No archaeological, genetic, linguistic or written historical evidence exists of the original Assyrian and Mesopotamian population being exterminated, removed, bred out or replaced in the aftermath of the fall of the Assyrian Empire, modern contemporary scholarship "almost unilaterally" supports Assyrian continuity, recognizing the modern Assyrians as the ethnic, linguistic and genetic descendants of the East Assyrian-speaking population of Bronze Age and Iron Age Assyria, and Mesopotamia in general, which were composed of both the old native Assyrian population and of neighbouring settlers in the Assyrian heartland.

Larak was a city in Sumer that appears in some versions of the Sumerian King List as the third of five cities to exercise kingship in the antediluvian era. Its patron deity was Pabilsag, a Ninurta-like warrior god additionally associated with judgment, medicine and the underworld, usually portrayed as the husband of Ninisina. Gasan-aste, a version of the healing goddess Ninisina was worshiped at Larak.

The timeline of ancient Assyria can be broken down into three main eras: the Old Assyrian period, Middle Assyrian Empire, and Neo-Assyrian Empire. Modern scholars typically also recognize an Early period preceding the Old Assyrian period and a post-imperial period succeeding the Neo-Assyrian period.

The Sargonid dynasty was the final ruling dynasty of Assyria, ruling as kings of Assyria during the Neo-Assyrian Empire for just over a century from the ascent of Sargon II in 722 BC to the fall of Assyria in 609 BC. Although Assyria would ultimately fall during their rule, the Sargonid dynasty ruled the country during the apex of its power and Sargon II's three immediate successors Sennacherib, Esarhaddon and Ashurbanipal are generally regarded as three of the greatest Assyrian monarchs. Though the dynasty encompasses seven Assyrian kings, two vassal kings in Babylonia and numerous princes and princesses, the term Sargonids is sometimes used solely for Sennacherib, Esarhaddon and Ashurbanipal.

The Gambulu, Gambulai, or Gambuli were a tribe of Arameans in ancient Babylonia. They were the most powerful tribe along the eastern border of Babylonia, or in the south toward the border with Elam. It is difficult to pinpoint their exact location. H. W. F. Saggs places them "south of the Diyala river toward the Elamite border."

Dur-Athara or Dur-Atkhara, more properly known as Dur-abi-hara, was an ancient city in Southern Babylonia. Babylonian king Marduk-apla-iddina II fortified the city as part of his war against Sargon II (722-705), moving "the entire Gambulu tribe" into it. He dug a canal from the nearby Surappu river, causing the entire area to flood, leaving the city in the position of an "artificial island". Sargon's attack of Dur-Athara came in 710, and according to Assyrian annals was completed in a single day. Sargon plundered the city and deported 18,400 people from it, after which Gambulu leaders offered tribute. Sargon gave the city a new name, Dur-Nabu, and made it the capital of the province of Gambulu.

Bit-Amukani was a tribe, proto-state founded by Chaldeans in southern Mesopotamia which stretched from southeast of Nippur to the area of Uruk. It is considered as one of the most powerful Chaldean tribes, next to Bīt-Iakin and Bīt-Dakkūri.