Renton is a city in King County, Washington, United States, and an inner-ring suburb of Seattle. Situated 11 miles (18 km) southeast of downtown Seattle, Renton straddles the southeast shore of Lake Washington, at the mouth of the Cedar River. As of the 2020 census, the population of Renton was 106,785, up from 90,927 at the 2010 census. The city is currently the 6th most populous municipality in greater Seattle and the 8th most populous city in Washington.

The Dormant Commerce Clause, or Negative Commerce Clause, in American constitutional law, is a legal doctrine that courts in the United States have inferred from the Commerce Clause in Article I of the US Constitution. The primary focus of the doctrine is barring state protectionism. The Dormant Commerce Clause is used to prohibit state legislation that discriminates against, or unduly burdens, interstate or international commerce. Courts first determine whether a state regulation discriminates on its face against interstate commerce or whether it has the purpose or effect of discriminating against interstate commerce. If the statute is discriminatory, the state has the burden to justify both the local benefits flowing from the statute and to show the state has no other means of advancing the legitimate local purpose.

R.A.V. v. City of St. Paul, 505 U.S. 377 (1992), is a case of the United States Supreme Court that unanimously struck down St. Paul's Bias-Motivated Crime Ordinance and reversed the conviction of a teenager, referred to in court documents only as R.A.V., for burning a cross on the lawn of an African-American family since the ordinance was held to violate the First Amendment's protection of freedom of speech. The Court reasoned that an ordinance like this constitutes "viewpoint discrimination" which may have the effect of driving certain ideas from the marketplace of ideas.

Reno v. American Civil Liberties Union, 521 U.S. 844 (1997), was a landmark decision of the Supreme Court of the United States, unanimously ruling that anti-indecency provisions of the 1996 Communications Decency Act violated the First Amendment's guarantee of freedom of speech. This was the first major Supreme Court ruling on the regulation of materials distributed via the Internet.

Hammer v. Dagenhart, 247 U.S. 251 (1918), was a United States Supreme Court decision in which the Court struck down a federal law regulating child labor. The decision was overruled by United States v. Darby Lumber Co. (1941).

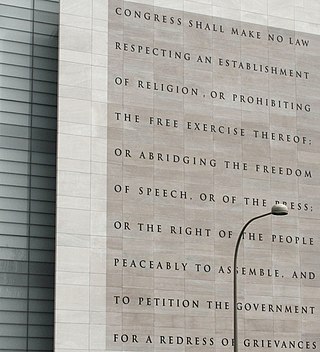

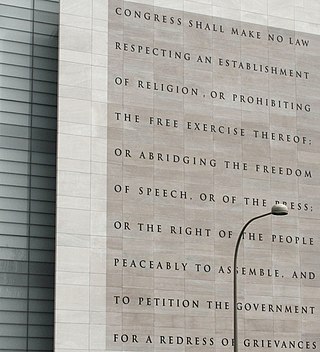

In the United States, freedom of speech and expression is strongly protected from government restrictions by the First Amendment to the U.S. Constitution, many state constitutions, and state and federal laws. Freedom of speech, also called free speech, means the free and public expression of opinions without censorship, interference and restraint by the government. The term "freedom of speech" embedded in the First Amendment encompasses the decision what to say as well as what not to say. The Supreme Court of the United States has recognized several categories of speech that are given lesser or no protection by the First Amendment and has recognized that governments may enact reasonable time, place, or manner restrictions on speech. The First Amendment's constitutional right of free speech, which is applicable to state and local governments under the incorporation doctrine, prevents only government restrictions on speech, not restrictions imposed by private individuals or businesses unless they are acting on behalf of the government. However, It can be restricted by time, place and manner in limited circumstances. Some laws may restrict the ability of private businesses and individuals from restricting the speech of others, such as employment laws that restrict employers' ability to prevent employees from disclosing their salary to coworkers or attempting to organize a labor union.

Rust v. Sullivan, 500 U.S. 173 (1991), was a case in the United States Supreme Court that upheld Department of Health and Human Services regulations prohibiting employees in federally funded family-planning facilities from counseling a patient on abortion. The department had removed all family planning programs that involving abortions. Physicians and clinics challenged this decision within the Supreme Court, arguing that the First Amendment was violated due to the implementation of this new policy. The Supreme Court, by a 5–4 verdict, allowed the regulation to go into effect, holding that the regulation was a reasonable interpretation of the Public Health Service Act, and that the First Amendment is not violated when the government merely chooses to "fund one activity to the exclusion of another."

Virginia v. Black, 538 U.S. 343 (2003), was a landmark decision of the Supreme Court of the United States in which the Court held, 5–4, that any state statute banning cross burning on the basis that it constitutes prima facie evidence of intent to intimidate is a violation of the First Amendment to the Constitution. Such a provision, the Court argued, blurs the distinction between proscribable "threats of intimidation" and the Ku Klux Klan's protected "messages of shared ideology". In the case, three defendants were convicted in two separate cases of violating a Virginia statute against cross burning. However, cross-burning can be a criminal offense if the intent to intimidate is proven. It was argued by former Solicitor General of Virginia, William Hurd and Rodney A. Smolla.

Intermediate scrutiny, in U.S. constitutional law, is the second level of deciding issues using judicial review. The other levels are typically referred to as rational basis review and strict scrutiny.

Central Hudson Gas & Electric Corp. v. Public Service Commission, 447 U.S. 557 (1980), was an important case decided by the United States Supreme Court that laid out a four-part test for determining when restrictions on commercial speech violated the First Amendment of the United States Constitution. Justice Powell wrote the opinion of the court. Central Hudson Gas & Electric Corp. had challenged a Public Service Commission regulation that prohibited promotional advertising by electric utilities. Justice Brennan, Justice Blackmun, and Justice Stevens wrote separate concurring opinions, and the latter two were both joined by Justice Brennan. Justice Rehnquist dissented.

An adult movie theater is a euphemistic term for a movie theater dedicated to the exhibition of pornographic films.

Erznoznik v. City of Jacksonville, 422 U.S. 205 (1975), is a United States Supreme Court case concerning a city ordinance prohibiting the showing of films containing nudity by a drive-in theater located in Jacksonville, Florida.

Spectator Magazine was an American weekly newsmagazine published and distributed in the San Francisco Bay Area from 1978 until October 2005. The magazine had its historical roots in the ‘60s underground weekly, The Berkeley Barb, first published on August 13, 1965. In addition to political free speech issues, the libertarian values of Barb founder Max Scherr and staff included sexual freedom, which led to the acceptance of adult ads into the pages of the newspaper. In 1978, The Barb management decided to discontinue adult ads in order to try to get mainstream ads, such as liquor, and cigarette ads. The staff of the Adult Ads Center Section decided to continue on as a new and separate publication, and thus Spectator Magazine was born. The last Berkeley Barb was published July 3, 1980 when the publication went under due to a lack of ads revenues.

Barnes v. Glen Theatre, Inc., 501 U.S. 560 (1991), was a landmark decision of the U.S. Supreme Court concerning the First Amendment and the ability of the government to outlaw certain forms of expressive conduct. It ruled that the state has the constitutional authority to ban public nudity, even as part of expressive conduct such as dancing, because it furthers a substantial government interest in protecting the morality and order of society. This case is perhaps best summarized by a sentence in Justice Souter's concurring opinion, which is often paraphrased as "Nudity itself is not inherently expressive conduct."

Posadas de Puerto Rico Associates v. Tourism Co. of Puerto Rico, 478 U.S. 328 (1986), was a 1986 appeal to the Supreme Court of the United States to determine whether Puerto Rico's Games of Chance Act of 1948 is in legal compliance with the United States Constitution, specifically as regards freedom of speech, equal protection and due process. In a 5–4 decision, the Supreme Court held that the Puerto Rico government (law) could restrict advertisement for casino gambling from being targeted to residents, even if the activity itself was legal and advertisement to tourists was permitted. The U.S. Supreme Court affirmed the Puerto Rico Supreme Court conclusion, as construed by the Puerto Rico Superior Court, that the Act and regulations do not facially violate the First Amendment, nor did it violate the due process or Equal Protection Clauses of the Fourteenth Amendment.

Los Angeles v. Alameda Books, Inc., 535 U.S. 425 (2002), was a United States Supreme Court case on the controversial issue of adult bookstore zoning in the city of Los Angeles. Zoning laws dictated that no adult bookstores could be within five hundred feet of a public park, or religious establishment, or within 1000 feet of another adult establishment. However, Alameda Books, Inc. and Highland Books, Inc. were two adult stores that operated under one roof. They sued Los Angeles, stating the ordinance violated the First Amendment. The district court concurred with the stores, stating that the 1977 study stating there was a higher crime rate in areas with adult stores, which the law was based upon, did not support a reasonable belief that multiple-use adult establishments produce the secondary effects the city asserted as content-neutral justifications for its restrictions on adult stores. The Court of Appeals upheld this verdict, and found that even if the ordinance were content neutral, the city failed to present evidence upon which it could reasonably rely to demonstrate that its regulation of multiple-use establishments was designed to serve its substantial interest in reducing crime. However, the Supreme Court ruled in favor of the city. This reversed the decision of the lower court. This case was argued on December 4, 2001; certiorari was granted on March 5, 2001. "City of Los Angeles v. Alameda Books, 00-799, didn't involve the kind of adult material that can be regulated by the government, but rather the extent to which cities can ban "one-stop shopping" sex-related businesses."

United States obscenity law deals with the regulation or suppression of what is considered obscenity and therefore not protected speech under the First Amendment to the United States Constitution. In the United States, discussion of obscenity typically relates to defining what pornography is obscene, as well as to issues of freedom of speech and of the press, otherwise protected by the First Amendment to the Constitution of the United States. Issues of obscenity arise at federal and state levels. State laws operate only within the jurisdiction of each state, and there are differences among such laws. Federal statutes ban obscenity and child pornography produced with real children. Federal law also bans broadcasting of "indecent" material during specified hours.

Voyeur Dorm, L.C. v. City of Tampa, 265 F.3d 1232, was a case decided by the 11th Circuit Court of Appeals, in which the court decided whether an adult-oriented website called Voyeur Dorm could be defined as "adult entertainment establishment" under the city's zoning codes. The circuit court was unanimous in its decision that the zoning codes did not apply to an online-only business.

Chamber of Commerce v. Brown, 554 U.S. 60 (2008), is a United States labor law case, concerning the scope of federal preemption against state law for labor rights.

Heller v. New York, 413 U.S. 483 (1973), was a United States Supreme Court decision which upheld that states could make laws limiting the distribution of obscene material, provided that these laws were consistent with the Miller test for obscene material established by the Supreme Court in Miller v. California, 413 U.S. 15 (1973). Heller was initially convicted for showing a sexually explicit film in the movie theater which he owned, under New York Penal Law § 235.0 which stated that and individual “is guilty of obscenity when, knowing its content and character, he 1. Promotes, or possesses with intent to promote, any obscene material; or 2. Produces, presents or directs an obscene performance or participates in a portion thereof which is obscene or which contributes to its obscenity."