Related Research Articles

A sarcoma is a malignant tumor, a type of cancer that arises from cells of mesenchymal origin. Connective tissue is a broad term that includes bone, cartilage, fat, vascular, or other structural tissues, and sarcomas can arise in any of these types of tissues. As a result, there are many subtypes of sarcoma, which are classified based on the specific tissue and type of cell from which the tumor originates. Sarcomas are primary connective tissue tumors, meaning that they arise in connective tissues. This is in contrast to secondary connective tissue tumors, which occur when a cancer from elsewhere in the body spreads to the connective tissue. Sarcomas are one of five different types of cancer, classified by the cell type from which they originate. The word sarcoma is derived from the Greek σάρκωμα sarkōma 'fleshy excrescence or substance', itself from σάρξsarx meaning 'flesh'.

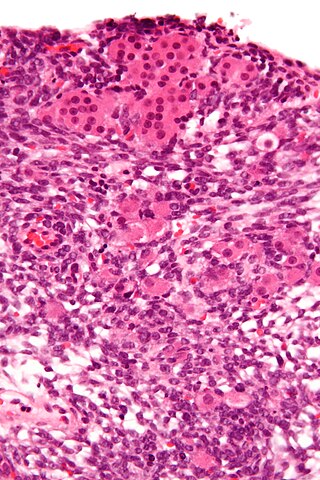

Rhabdomyosarcoma (RMS) is a highly aggressive form of cancer that develops from mesenchymal cells that have failed to fully differentiate into myocytes of skeletal muscle. Cells of the tumor are identified as rhabdomyoblasts.

Sertoli–Leydig cell tumour is a group of tumors composed of variable proportions of Sertoli cells, Leydig cells, and in the case of intermediate and poorly differentiated neoplasms, primitive gonadal stroma and sometimes heterologous elements.

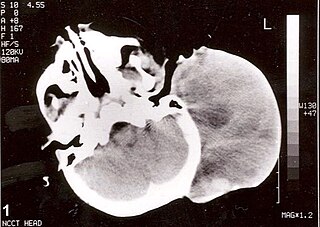

Desmoplastic small-round-cell tumor (DSRCT) is an aggressive and rare cancer that primarily occurs as masses in the abdomen. Other areas affected may include the lymph nodes, the lining of the abdomen, diaphragm, spleen, liver, chest wall, skull, spinal cord, large intestine, small intestine, bladder, brain, lungs, testicles, ovaries, and the pelvis. Reported sites of metastatic spread include the liver, lungs, lymph nodes, brain, skull, and bones. It is characterized by the EWS-WT1 fusion protein.

Pleuropulmonary blastoma (PPB) is a rare cancer originating in the lung or pleural cavity. It occurs most often in infants and young children but also has been reported in adults. In a retrospective review of 204 children with lung tumors, pleuropulmonary blastoma and carcinoid tumor were the most common primary tumors. Pleuropulmonary blastoma is regarded as malignant. The male:female ratio is approximately one.

A blastoma is a type of cancer, more common in children, that is caused by malignancies in precursor cells, often called blasts. Examples are nephroblastoma, medulloblastoma, and retinoblastoma. The suffix -blastoma is used to imply a tumor of primitive, incompletely differentiated cells, e.g., chondroblastoma is composed of cells resembling the precursor of chondrocytes.

In pathology, grading is a measure of the cell appearance in tumors and other neoplasms. Some pathology grading systems apply only to malignant neoplasms (cancer); others apply also to benign neoplasms. The neoplastic grading is a measure of cell anaplasia in the sampled tumor and is based on the resemblance of the tumor to the tissue of origin. Grading in cancer is distinguished from staging, which is a measure of the extent to which the cancer has spread.

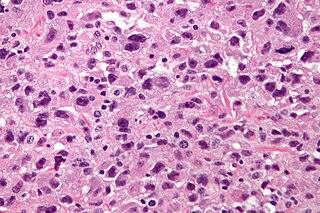

Undifferentiated pleomorphic sarcoma (UPS), also termed pleomorphic myofibrosarcoma, high-grade myofibroblastic sarcoma, and high-grade myofibrosarcoma, is characterized by the World Health Organization (WHO), 2020, as a rare, poorly differentiated neoplasm, i.e. an abnormal growth of cells that have an unclear identity and/or cell of origin. WHO classified it as one of the undifferentiated/unclassified sarcomas in the category of tumors of uncertain differentiation. Sarcomas are cancers known or thought to derive from mesenchymal stem cells that typically develop in bone, muscle, fat, blood vessels, lymphatic vessels, tendons, and ligaments. More than 70 sarcoma subtypes have been described. The UPS subtype of these sarcomas consists of tumor cells that are poorly differentiated and may appear as spindle-shaped cells, histiocytes, and giant cells. UPS is considered a diagnosis that defies formal sub-classification after thorough histologic, immunohistochemical, and ultrastructural examinations fail to identify the type of cells involved.

Sarcoma botryoides or botryoid sarcoma is a subtype of embryonal rhabdomyosarcoma, that can be observed in the walls of hollow, mucosa lined structures such as the nasopharynx, common bile duct, urinary bladder of infants and young children or the vagina in females, typically younger than age 8. The name comes from the gross appearance of "grape bunches".

Alveolar rhabdomyosarcoma (ARMS) is a subtype of the rhabdomyosarcoma soft tissue cancer family whose lineage is from mesenchymal cells and are related to skeletal muscle cells. ARMS tumors resemble the alveolar tissue in the lungs. Tumor location varies from patient to patient, but is commonly found in the head and neck region, male and female urogenital tracts, the torso, and extremities. Two fusion proteins can be associated with ARMS, but are not necessary, PAX3-FKHR. and PAX7-FKHR. In children and adolescents ARMS accounts for about 1 percent of all malignancies, has an incidence rate of 1 per million, and most cases occur sporadically with no genetic predisposition. PAX3-FOXO1 is now known to drive cancer-promoting gene expression programs through creation of distant genetic elements called super enhancers.

Malignant ectomesenchymoma(MEM) is a rare, fast-growing tumor of the nervous system or soft tissue that occurs in children and young adults. MEM is part of a group of small round blue cell tumors which includes neuroblastoma, rhabdomyosarcoma, non-Hodgkin's lymphoma, and the Ewing's family of tumors.

Ectomesenchymoma is a rare, fast-growing tumor of the nervous system or soft tissue that occurs mainly in children, although cases have been reported in patients up to age 60. Ectomesenchymomas may form in the head and neck, abdomen, perineum, scrotum, or limbs. Also called malignant ectomesenchymoma.

Large cell lung carcinoma with rhabdoid phenotype (LCLC-RP) is a rare histological form of lung cancer, currently classified as a variant of large cell lung carcinoma (LCLC). In order for a LCLC to be subclassified as the rhabdoid phenotype variant, at least 10% of the malignant tumor cells must contain distinctive structures composed of tangled intermediate filaments that displace the cell nucleus outward toward the cell membrane. The whorled eosinophilic inclusions in LCLC-RP cells give it a microscopic resemblance to malignant cells found in rhabdomyosarcoma (RMS), a rare neoplasm arising from transformed skeletal muscle. Despite their microscopic similarities, LCLC-RP is not associated with rhabdomyosarcoma.

Sarcomatoid carcinoma, sometimes referred to as pleomorphic carcinoma, is a relatively uncommon form of cancer whose malignant cells have histological, cytological, or molecular properties of both epithelial tumors ("carcinoma") and mesenchymal tumors ("sarcoma"). It is believed that sarcomatoid carcinomas develop from more common forms of epithelial tumors.

Embryonal rhabdomyosarcoma (EMRS) is a rare histological form of cancer in the connective tissue wherein the mesenchymally-derived malignant cells resemble the primitive developing skeletal muscle of the embryo. It is the most common soft tissue sarcoma occurring in children. Embryonal rhabdomyosarcoma is also known as PAX-fusion negative or fusion-negative rhabdomyosarcoma, as tumors of this subtype are unified by their lack of a PAX3-FOXO1 fusion oncogene. Fusion status refers to the presence or absence of a fusion gene, which is a gene formed from joining two different genes together through DNA rearrangements. These types of tumors are classified as embryonal rhabdomyosarcoma "because of their remarkable resemblance to developing embryonic and fetal skeletal muscle."

Vulvar tumors are those neoplasms of the vulva. Vulvar and vaginal neoplasms make up a small percentage (3%) of female genital cancers. They can be benign or malignant. Vulvar neoplasms are divided into cystic or solid lesions and other mixed types. Vulvar cancers are those malignant neoplasms that originate from vulvar epithelium, while vulvar sarcomas develop from non-epithelial cells such as bone, cartilage, fat, muscle, blood vessels, or other connective or supportive tissue. Epithelial and mesenchymal tissue are the origin of vulvar tumors.

Fibroblastic and myofibroblastic tumors (FMTs) develop from the mesenchymal stem cells which differentiate into fibroblasts and/or the myocytes/myoblasts that differentiate into muscle cells. FMTs are a heterogeneous group of soft tissue neoplasms. The World Health Organization (2020) defined tumors as being FMTs based on their morphology and, more importantly, newly discovered abnormalities in the expression levels of key gene products made by these tumors' neoplastic cells. Histopathologically, FMTs consist of neoplastic connective tissue cells which have differented into cells that have microscopic appearances resembling fibroblasts and/or myofibroblasts. The fibroblastic cells are characterized as spindle-shaped cells with inconspicuous nucleoli that express vimentin, an intracellular protein typically found in mesenchymal cells, and CD34, a cell surface membrane glycoprotein. Myofibroblastic cells are plumper with more abundant cytoplasm and more prominent nucleoli; they express smooth muscle marker proteins such as smooth muscle actins, desmin, and caldesmon. The World Health Organization further classified FMTs into four tumor forms based on their varying levels of aggressiveness: benign, intermediate, intermediate, and malignant.

Low-grade myofibroblastic sarcoma (LGMS) is a subtype of the malignant sarcomas. As it is currently recognized, LGMS was first described as a rare, atypical myofibroblastic tumor by Mentzel et al. in 1998. Myofibroblastic sarcomas had been divided into low-grade myofibroblastic sarcomas, intermediate‐grade myofibroblasic sarcomas, i.e. IGMS, and high‐grade myofibroblasic sarcomas, i.e. HGMS based on their microscopic morphological, immunophenotypic, and malignancy features. LGMS and IGMS are now classified together by the World Health Organization (WHO), 2020, in the category of intermediate fibroblastic and myofibroblastic tumors. WHO, 2020, classifies HGMS as a soft tissue tumor in the category of tumors of uncertain differentiation. This article follows the WHO classification: here, LGMS includes IGMS but not HGMS which is a more aggressive and metastasizing tumor than LGMS and consists of cells of uncertain origin.

References

- ↑ Holland-Frei Cancer Medicine (6th ed.). BC Decker. 2003. ISBN 978-1-55009-213-4.

- ↑ Rosenberg AE (2010). "Bones, Joints, and Soft Tissue Tumors". In Robbins SL, Kumar V, Cotran RS (eds.). Robbins and Cotran pathologic basis of disease (8th ed.). Philadelphia, PA: Saunders/Elsevier. p. 1253. ISBN 978-1-4160-3121-5. OCLC 212375916.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 Leiner J, Le Loarer F (January 2020). "The current landscape of rhabdomyosarcomas: an update". Virchows Archiv. 476 (1): 97–108. doi:10.1007/s00428-019-02676-9. PMID 31696361. S2CID 207911529.

- ↑ Merrow Jr AC (2017). Diagnostic imaging. Pediatrics (3rd ed.). Philadelphia, PA. ISBN 978-0-323-44321-0. OCLC 964919393.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 31 32 33 Angelico G, Piombino E, Broggi G, Motta F, Spadola S (2017). "Rhabdomyoblasts in Pediatric Tumors: A Review with Emphasis on their Diagnostic Utility". Journal of Stem Cell Therapy and Transplantation. 1 (1): 008–016. doi: 10.29328/journal.jsctt.1001002 .

- ↑ Robertus JL, Harms G, Blokzijl T, Booman M, de Jong D, van Imhoff G, et al. (April 2009). "Specific expression of miR-17-5p and miR-127 in testicular and central nervous system diffuse large B-cell lymphoma". Modern Pathology. 22 (4): 547–555. doi:10.1038/modpathol.2009.10. PMID 19287466. S2CID 12768829.

- ↑ Sweeney HL, Hammers DW (February 2018). "Muscle Contraction". Cold Spring Harbor Perspectives in Biology. 10 (2): a023200. doi:10.1101/cshperspect.a023200. PMC 5793755 . PMID 29419405.

- ↑ "What Is Cancer? - National Cancer Institute". www.cancer.gov. 2007-09-17. Retrieved 2022-04-14.

- ↑ "Causes". stanfordhealthcare.org. Retrieved 2022-04-14.

- ↑ Marcus PM (November 2019). Population measures: cancer screening's impact. National Cancer Institute (US).

- 1 2 Mukherjee S (2012). The emperor of all maladies : a biography of cancer. Gale, Cengage Learning. ISBN 978-1-4104-4715-9. OCLC 865341800.

- ↑ "Treatment for Cancer - National Cancer Institute". www.cancer.gov. 2015-04-29. Retrieved 2022-04-14.

- 1 2 Clevenger JA, Foster RS, Ulbright TM (October 2009). "Differentiated rhabdomyomatous tumors after chemotherapy for metastatic testicular germ-cell tumors: a clinicopathological study of seven cases mandating separation from rhabdomyosarcoma". Modern Pathology. 22 (10): 1361–1366. doi: 10.1038/modpathol.2009.108 . PMID 19633644. S2CID 205199458.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Jeyaraju M, Macatangay RA, Munchel AT, York TA, Montgomery EA, Kallen ME (2021-11-08). Ahmed AA (ed.). "Embryonal Rhabdomyosarcoma with Posttherapy Cytodifferentiation and Aggressive Clinical Course". Case Reports in Pathology. 2021: 1800854. doi: 10.1155/2021/1800854 . PMC 8592761 . PMID 34790419.

- ↑ Balitzer D, McCalmont TH, Horvai AE (2015-12-10). "Adipocyte-Like Differentiation in a Posttreatment Embryonal Rhabdomyosarcoma". Case Reports in Pathology. 2015: 406739. doi: 10.1155/2015/406739 . PMC 4689918 . PMID 26783483.

- ↑ Qualman SJ, Coffin CM, Newton WA, Hojo H, Triche TJ, Parham DM, Crist WM (Nov 1998). "Intergroup Rhabdomyosarcoma Study: update for pathologists". Pediatric and Developmental Pathology. 1 (6): 550–561. doi:10.1007/s100249900076. PMID 9724344. S2CID 25785779.

- 1 2 3 4 Chaudhary N, Shet T, Borker A (January 2013). "Infantile rhabdomyofibrosarcoma: A potentially underdiagnosed aggressive tumor". International Journal of Applied & Basic Medical Research. 3 (1): 66–68. doi: 10.4103/2229-516X.112244 . PMC 3678685 . PMID 23776843.

- ↑ Farid M, Demicco EG, Garcia R, Ahn L, Merola PR, Cioffi A, Maki RG (February 2014). "Malignant peripheral nerve sheath tumors". The Oncologist. 19 (2): 193–201. doi:10.1634/theoncologist.2013-0328. PMC 3926794 . PMID 24470531.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Bishop JA, Thompson LD, Cardesa A, Barnes L, Lewis JS, Triantafyllou A, et al. (December 2015). "Rhabdomyoblastic Differentiation in Head and Neck Malignancies Other Than Rhabdomyosarcoma". Head and Neck Pathology. 9 (4): 507–518. doi:10.1007/s12105-015-0624-2. PMC 4651923 . PMID 25757816.

- ↑ Nael A, Siaghani P, Wu WW, Nael K, Shane L, Romansky SG (2014). "Metastatic malignant ectomesenchymoma initially presenting as a pelvic mass: report of a case and review of literature". Case Reports in Pediatrics. 2014: 792925. doi: 10.1155/2014/792925 . PMC 4227373 . PMID 25405050.

- ↑ Huang SC, Alaggio R, Sung YS, Chen CL, Zhang L, Kao YC, et al. (July 2016). "Frequent HRAS Mutations in Malignant Ectomesenchymoma: Overlapping Genetic Abnormalities With Embryonal Rhabdomyosarcoma". The American Journal of Surgical Pathology. 40 (7): 876–885. doi:10.1097/PAS.0000000000000612. PMC 4905780 . PMID 26872011.

- 1 2 3 Maes P, Delemarre J, de Kraker J, Ninane J (September 1999). "Fetal rhabdomyomatous nephroblastoma: a tumour of good prognosis but resistant to chemotherapy". European Journal of Cancer. 35 (9): 1356–1360. doi:10.1016/s0959-8049(99)00128-8. PMID 10658527.

- ↑ Yousem SA, Wick MR, Randhawa P, Manivel JC (February 1990). "Pulmonary blastoma. An immunohistochemical analysis with comparison with fetal lung in its pseudoglandular stage". American Journal of Clinical Pathology. 93 (2): 167–175. doi:10.1093/ajcp/93.2.167. PMID 2301281.