In linguistics, declension is the changing of the form of a word, generally to express its syntactic function in the sentence, by way of some inflection. Declensions may apply to nouns, pronouns, adjectives, adverbs, and determiners to indicate number, case, gender, and a number of other grammatical categories. Meanwhile, the inflectional change of verbs is called conjugation.

Novial is a constructed international auxiliary language (IAL) for universal human communication between speakers of different native languages. It was devised by Otto Jespersen, a Danish linguist who had been involved in the Ido movement that evolved from Esperanto at the beginning of the 20th century, and participated later in the development of Interlingua. The name means 'new' + 'international auxiliary language'.

Morphological derivation, in linguistics, is the process of forming a new word from an existing word, often by adding a prefix or suffix, such as un- or -ness. For example, unhappy and happiness derive from the root word happy.

Russian grammar employs an Indo-European inflexional structure, with considerable adaptation.

Spanish verbs form one of the more complex areas of Spanish grammar. Spanish is a relatively synthetic language with a moderate to high degree of inflection, which shows up mostly in Spanish conjugation.

Chavacano or Chabacano is a group of Spanish-based creole language varieties spoken in the Philippines. The variety spoken in Zamboanga City, located in the southern Philippine island group of Mindanao, has the highest concentration of speakers. Other currently existing varieties are found in Cavite City and Ternate, located in the Cavite province on the island of Luzon. Chavacano is the only Spanish-based creole in Asia. The 2020 Census of Population and Housing counted 106,000 households generally speaking Chavacano.

Spanish is a grammatically inflected language, which means that many words are modified ("marked") in small ways, usually at the end, according to their changing functions. Verbs are marked for tense, aspect, mood, person, and number. Nouns follow a two-gender system and are marked for number. Personal pronouns are inflected for person, number, gender, and a very reduced case system; the Spanish pronominal system represents a simplification of the ancestral Latin system.

In some of the Romance languages the copula, the equivalent of the verb to be in English, is relatively complex compared to its counterparts in other languages. A copula is a word that links the subject of a sentence with a predicate. Whereas English has one main copula verb some Romance languages have more complex forms.

In linguistics, a word stem is a part of a word responsible for its lexical meaning. Typically, a stem remains unmodified during inflection with few exceptions due to apophony

Swedish is descended from Old Norse. Compared to its progenitor, Swedish grammar is much less characterized by inflection. Modern Swedish has two genders and no longer conjugates verbs based on person or number. Its nouns have lost the morphological distinction between nominative and accusative cases that denoted grammatical subject and object in Old Norse in favor of marking by word order. Swedish uses some inflection with nouns, adjectives, and verbs. It is generally a subject–verb–object (SVO) language with V2 word order.

Dominican Spanish is Spanish as spoken in the Dominican Republic; and also among the Dominican diaspora, most of whom live in the United States, chiefly in New York City, New Jersey, Connecticut, Rhode Island, Massachusetts, Pennsylvania, and Florida.

In linguistics, a suffix is an affix which is placed after the stem of a word. Common examples are case endings, which indicate the grammatical case of nouns and adjectives, and verb endings, which form the conjugation of verbs. Suffixes can carry grammatical information or lexical information . Inflection changes the grammatical properties of a word within its syntactic category. Derivational suffixes fall into two categories: class-changing derivation and class-maintaining derivation.

Eastern Lombard grammar reflects the main features of Romance languages: the word order of Eastern Lombard is usually SVO, nouns are inflected in number, adjectives agree in number and gender with the nouns, verbs are conjugated in tenses, aspects and moods and agree with the subject in number and person. The case system is present only for the weak form of the pronoun.

Ixcatec is a language spoken by the people of the Mexican village of Santa María Ixcatlan, in the northern part of the state of Oaxaca. The Ixcatec language belongs to the Popolocan branch of the Oto-manguean language family. It is believed to have been the second language to branch off from the others within the Popolocan subgroup, though there is a small debate over the relation it has to them.

In linguistic morphology, inflection is a process of word formation in which a word is modified to express different grammatical categories such as tense, case, voice, aspect, person, number, gender, mood, animacy, and definiteness. The inflection of verbs is called conjugation, and one can refer to the inflection of nouns, adjectives, adverbs, pronouns, determiners, participles, prepositions and postpositions, numerals, articles, etc., as declension.

In Spanish, grammatical gender is a linguistic feature that affects different types of words and how they agree with each other. It applies to nouns, adjectives, determiners, and pronouns. Every Spanish noun has a specific gender, either masculine or feminine, in the context of a sentence. Generally, nouns referring to males or male animals are masculine, while those referring to females are feminine. In terms of importance, the masculine gender is the default or unmarked, while the feminine gender is marked or distinct.

Portuguese verbs display a high degree of inflection. A typical regular verb has over fifty different forms, expressing up to six different grammatical tenses and three moods. Two forms are peculiar to Portuguese within the Romance languages:

Historical linguistics has made tentative postulations about and multiple varyingly different reconstructions of Proto-Germanic grammar, as inherited from Proto-Indo-European grammar. All reconstructed forms are marked with an asterisk (*).

Pidgin Delaware was a pidgin language that developed between speakers of Unami Delaware and Dutch traders and settlers on the Delaware River in the 1620s. The fur trade in the Middle Atlantic region led Europeans to interact with local native groups, and hence provided an impetus for the development of Pidgin Delaware. The Dutch were active in the fur trade beginning early in the seventeenth century, establishing trading posts in New Netherland, the name for the Dutch territory of the Middle Atlantic and exchanging trade goods for furs.

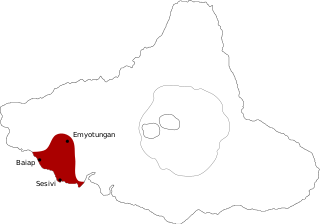

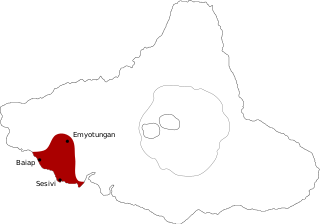

Daakaka is a native language of Ambrym, Vanuatu. It is spoken by about one thousand speakers in the south-western corner of the island.