Related Research Articles

An infection is the invasion of tissues by pathogens, their multiplication, and the reaction of host tissues to the infectious agent and the toxins they produce. An infectious disease, also known as a transmissible disease or communicable disease, is an illness resulting from an infection.

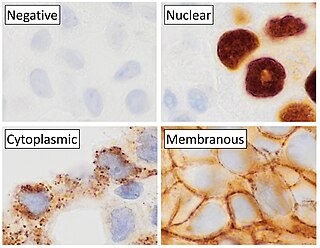

Immunoperoxidase is a type of immunostain used in molecular biology, medical research, and clinical diagnostics. In particular, immunoperoxidase reactions refer to a sub-class of immunohistochemical or immunocytochemical procedures in which the antibodies are visualized via a peroxidase-catalyzed reaction.

Plant pathology or phytopathology is the scientific study of plant diseases caused by pathogens and environmental conditions. Plant pathology involves the study of pathogen identification, disease etiology, disease cycles, economic impact, plant disease epidemiology, plant disease resistance, how plant diseases affect humans and animals, pathosystem genetics, and management of plant diseases.

Mycoplasma is a genus of bacteria that, like the other members of the class Mollicutes, lack a cell wall around their cell membranes. Peptidoglycan (murein) is absent. This characteristic makes them naturally resistant to antibiotics that target cell wall synthesis. They can be parasitic or saprotrophic. Several species are pathogenic in humans, including M. pneumoniae, which is an important cause of "walking" pneumonia and other respiratory disorders, and M. genitalium, which is believed to be involved in pelvic inflammatory diseases. Mycoplasma species are among the smallest organisms yet discovered, can survive without oxygen, and come in various shapes. For example, M. genitalium is flask-shaped, while M. pneumoniae is more elongated, many Mycoplasma species are coccoid. Hundreds of Mycoplasma species infect animals.

Humoral immunity is the aspect of immunity that is mediated by macromolecules – including secreted antibodies, complement proteins, and certain antimicrobial peptides – located in extracellular fluids. Humoral immunity is named so because it involves substances found in the humors, or body fluids. It contrasts with cell-mediated immunity. Humoral immunity is also referred to as antibody-mediated immunity.

An assay is an investigative (analytic) procedure in laboratory medicine, mining, pharmacology, environmental biology and molecular biology for qualitatively assessing or quantitatively measuring the presence, amount, or functional activity of a target entity. The measured entity is often called the analyte, the measurand, or the target of the assay. The analyte can be a drug, biochemical substance, chemical element or compound, or cell in an organism or organic sample. An assay usually aims to measure an analyte's intensive property and express it in the relevant measurement unit.

In biochemistry, immunostaining is any use of an antibody-based method to detect a specific protein in a sample. The term "immunostaining" was originally used to refer to the immunohistochemical staining of tissue sections, as first described by Albert Coons in 1941. However, immunostaining now encompasses a broad range of techniques used in histology, cell biology, and molecular biology that use antibody-based staining methods.

Immunofluorescence(IF) is a light microscopy-based technique that allows detection and localization of a wide variety of target biomolecules within a cell or tissue at a quantitative level. The technique utilizes the binding specificity of antibodies and antigens. The specific region an antibody recognizes on an antigen is called an epitope. Several antibodies can recognize the same epitope but differ in their binding affinity. The antibody with the higher affinity for a specific epitope will surpass antibodies with a lower affinity for the same epitope.

Immunohistochemistry (IHC) is a form of immunostaining. It involves the process of selectively identifying antigens (proteins) in cells and tissue, by exploiting the principle of antibodies binding specifically to antigens in biological tissues. Albert Hewett Coons, Ernest Berliner, Norman Jones and Hugh J Creech was the first to develop immunofluorescence in 1941. This led to the later development of immunohistochemistry.

Phytoplasmas are obligate intracellular parasites of plant phloem tissue and of the insect vectors that are involved in their plant-to-plant transmission. Phytoplasmas were discovered in 1967 by Japanese scientists who termed them mycoplasma-like organisms. Since their discovery, phytoplasmas have resisted all attempts at in vitro culture in any cell-free medium; routine cultivation in an artificial medium thus remains a major challenge. Phytoplasmas are characterized by the lack of a cell wall, a pleiomorphic or filamentous shape, a diameter normally less than 1 μm, and a very small genome.

Serology is the scientific study of serum and other body fluids. In practice, the term usually refers to the diagnostic identification of antibodies in the serum. Such antibodies are typically formed in response to an infection, against other foreign proteins, or to one's own proteins. In either case, the procedure is simple.

Hybridoma technology is a method for producing large numbers of identical antibodies. This process starts by injecting a mouse with an antigen that provokes an immune response. A type of white blood cell, the B cell, produces antibodies that bind to the injected antigen. These antibody producing B-cells are then harvested from the mouse and, in turn, fused with immortal myeloma cancer cells, to produce a hybrid cell line called a hybridoma, which has both the antibody-producing ability of the B-cell and the longevity and reproductivity of the myeloma. The hybridomas can be grown in culture, each culture starting with one viable hybridoma cell, producing cultures each of which consists of genetically identical hybridomas which produce one antibody per culture (monoclonal) rather than mixtures of different antibodies (polyclonal). The myeloma cell line that is used in this process is selected for its ability to grow in tissue culture and for an absence of antibody synthesis. In contrast to polyclonal antibodies, which are mixtures of many different antibody molecules, the monoclonal antibodies produced by each hybridoma line are all chemically identical.

A fluorescence microscope is an optical microscope that uses fluorescence instead of, or in addition to, scattering, reflection, and attenuation or absorption, to study the properties of organic or inorganic substances. "Fluorescence microscope" refers to any microscope that uses fluorescence to generate an image, whether it is a simple set up like an epifluorescence microscope or a more complicated design such as a confocal microscope, which uses optical sectioning to get better resolution of the fluorescence image.

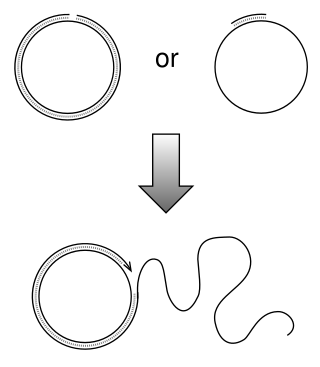

Rolling circle replication (RCR) is a process of unidirectional nucleic acid replication that can rapidly synthesize multiple copies of circular molecules of DNA or RNA, such as plasmids, the genomes of bacteriophages, and the circular RNA genome of viroids. Some eukaryotic viruses also replicate their DNA or RNA via the rolling circle mechanism.

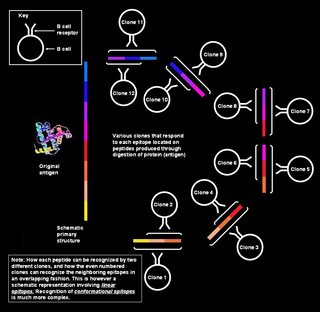

Polyclonal B cell response is a natural mode of immune response exhibited by the adaptive immune system of mammals. It ensures that a single antigen is recognized and attacked through its overlapping parts, called epitopes, by multiple clones of B cell.

Medical microbiology, the large subset of microbiology that is applied to medicine, is a branch of medical science concerned with the prevention, diagnosis and treatment of infectious diseases. In addition, this field of science studies various clinical applications of microbes for the improvement of health. There are four kinds of microorganisms that cause infectious disease: bacteria, fungi, parasites and viruses, and one type of infectious protein called prion.

Immunolabeling is a biochemical process that enables the detection and localization of an antigen to a particular site within a cell, tissue, or organ. Antigens are organic molecules, usually proteins, capable of binding to an antibody. These antigens can be visualized using a combination of antigen-specific antibody as well as a means of detection, called a tag, that is covalently linked to the antibody. If the immunolabeling process is meant to reveal information about a cell or its substructures, the process is called immunocytochemistry. Immunolabeling of larger structures is called immunohistochemistry.

Pathatrix is a high volume recirculating immuno magnetic-capture system developed by Thermo Fisher Scientific for the detection of pathogens in food and environmental samples.

Citrus psorosis ophiovirus is a plant pathogenic virus infecting citrus plants worldwide. It is considered the most serious and detrimental virus pathogen of these trees.

Sugarcane grassy shoot disease (SCGS), is associated with 'Candidatus Phytoplasma sacchari' which are small, pleomorphic, pathogenic mycoplasma that contribute to yield losses from 5% up to 20% in sugarcane. These losses are higher in the ratoon crop. A higher incidence of SCGS has been recorded in some parts of Southeast Asia and India, resulting in 100% loss in cane yield and sugar production.

References

- 1 2 3 Thomas, Sunil; Balasundaran, M (2001). "Purification of sandal spike phytoplasma for the production of polyclonal antibody". Current Science Online. 80 (12): 1489–94.

- ↑ Thomas, S.; Balasundaran, M. (1998). "In situ detection of phytoplasma in spike disease affected sandal using DAPI stain". Current Science. 74: 989–93.

- ↑ Thomas, Sunil; Balasundaran, M. (1999). "Detection of sandal spike phytoplasma by polymerase chain reaction". Current Science. 76 (12): 1574–6.

- ↑ Sunil, T.; Balasundaran, M. (2001). "Detection of sandal spike phytoplasma by immunomicroscopy". Plant Cell Biotechnology and Molecular Biology. 2: 41–8.