Related Research Articles

Cranial nerves are the nerves that emerge directly from the brain, of which there are conventionally considered twelve pairs. Cranial nerves relay information between the brain and parts of the body, primarily to and from regions of the head and neck, including the special senses of vision, taste, smell, and hearing.

The olfactory nerve, also known as the first cranial nerve, cranial nerve I, or simply CN I, is a cranial nerve that contains sensory nerve fibers relating to the sense of smell.

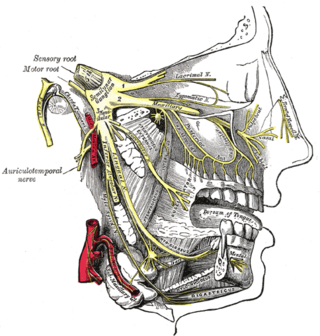

In neuroanatomy, the trigeminal nerve (lit. triplet nerve), also known as the fifth cranial nerve, cranial nerve V, or simply CN V, is a cranial nerve responsible for sensation in the face and motor functions such as biting and chewing; it is the most complex of the cranial nerves. Its name (trigeminal, from Latin tri- 'three', and -geminus 'twin') derives from each of the two nerves (one on each side of the pons) having three major branches: the ophthalmic nerve (V1), the maxillary nerve (V2), and the mandibular nerve (V3). The ophthalmic and maxillary nerves are purely sensory, whereas the mandibular nerve supplies motor as well as sensory (or "cutaneous") functions. Adding to the complexity of this nerve is that autonomic nerve fibers as well as special sensory fibers (taste) are contained within it.

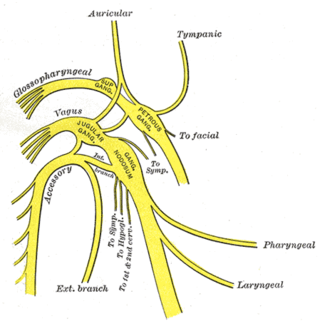

The glossopharyngeal nerve, also known as the ninth cranial nerve, cranial nerve IX, or simply CN IX, is a cranial nerve that exits the brainstem from the sides of the upper medulla, just anterior to the vagus nerve. Being a mixed nerve (sensorimotor), it carries afferent sensory and efferent motor information. The motor division of the glossopharyngeal nerve is derived from the basal plate of the embryonic medulla oblongata, whereas the sensory division originates from the cranial neural crest.

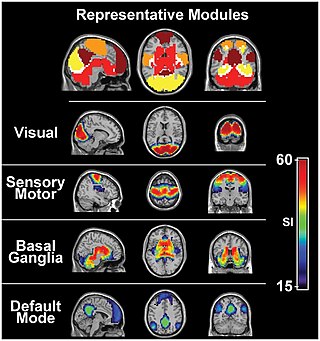

The sensory nervous system is a part of the nervous system responsible for processing sensory information. A sensory system consists of sensory neurons, neural pathways, and parts of the brain involved in sensory perception and interoception. Commonly recognized sensory systems are those for vision, hearing, touch, taste, smell, balance and visceral sensation. Sense organs are transducers that convert data from the outer physical world to the realm of the mind where people interpret the information, creating their perception of the world around them.

The somatic nervous system (SNS) is made up of nerves that link the brain and spinal cord to voluntary or skeletal muscles that are under conscious control as well as to skin sensory receptors. Specialized nerve fiber ends called sensory receptors are responsible for detecting information within and outside of the body.

Afferent nerve fibers are axons of sensory neurons that carry sensory information from sensory receptors to the central nervous system. Many afferent projections arrive at a particular brain region.

Stimulus modality, also called sensory modality, is one aspect of a stimulus or what is perceived after a stimulus. For example, the temperature modality is registered after heat or cold stimulate a receptor. Some sensory modalities include: light, sound, temperature, taste, pressure, and smell. The type and location of the sensory receptor activated by the stimulus plays the primary role in coding the sensation. All sensory modalities work together to heighten stimuli sensation when necessary.

The olfactory system or sense of smell is the sensory system used for smelling (olfaction). Olfaction is one of the special senses, that have directly associated specific organs. Most mammals and reptiles have a main olfactory system and an accessory olfactory system. The main olfactory system detects airborne substances, while the accessory system senses fluid-phase stimuli.

Sensory neurons, also known as afferent neurons, are neurons in the nervous system, that convert a specific type of stimulus, via their receptors, into action potentials or graded receptor potentials. This process is called sensory transduction. The cell bodies of the sensory neurons are located in the dorsal ganglia of the spinal cord.

Neuralgia is pain in the distribution of a nerve or nerves, as in intercostal neuralgia, trigeminal neuralgia, and glossopharyngeal neuralgia.

Ageusia is the loss of taste functions of the tongue, particularly the inability to detect sweetness, sourness, bitterness, saltiness, and umami. It is sometimes confused with anosmia – a loss of the sense of smell. Because the tongue can only indicate texture and differentiate between sweet, sour, bitter, salty, and umami, most of what is perceived as the sense of taste is actually derived from smell. True ageusia is relatively rare compared to hypogeusia – a partial loss of taste – and dysgeusia – a distortion or alteration of taste.

In medicine and anatomy, the special senses are the senses that have specialized organs devoted to them:

The lingual nerve carries sensory innervation from the anterior two-thirds of the tongue. It contains fibres from both the mandibular division of the trigeminal nerve (CN V3) and from the facial nerve (CN VII). The fibres from the trigeminal nerve are for touch, pain and temperature (general sensation), and the ones from the facial nerve are for taste (special sensation).

The cranial nerve exam is a type of neurological examination. It is used to identify problems with the cranial nerves by physical examination. It has nine components. Each test is designed to assess the status of one or more of the twelve cranial nerves (I-XII). These components correspond to testing the sense of smell (I), visual fields and acuity (II), eye movements and pupils, sensory function of face (V), strength of facial (VII) and shoulder girdle muscles (XI), hearing and balance, taste, pharyngeal movement and reflex, tongue movements (XII).

Dysosmia is a disorder described as any qualitative alteration or distortion of the perception of smell. Qualitative alterations differ from quantitative alterations, which include anosmia and hyposmia. Dysosmia can be classified as either parosmia or phantosmia. Parosmia is a distortion in the perception of an odorant. Odorants smell different from what one remembers. Phantosmia is the perception of an odor when no odorant is present. The cause of dysosmia still remains a theory. It is typically considered a neurological disorder and clinical associations with the disorder have been made. Most cases are described as idiopathic and the main antecedents related to parosmia are URTIs, head trauma, and nasal and paranasal sinus disease. Dysosmia tends to go away on its own but there are options for treatment for patients that want immediate relief.

The gustatory nucleus is the rostral part of the solitary nucleus located in the medulla. The gustatory nucleus is associated with the sense of taste and has two sections, the rostral and lateral regions. A close association between the gustatory nucleus and visceral information exists for this function in the gustatory system, assisting in homeostasis - via the identification of food that might be possibly poisonous or harmful for the body. There are many gustatory nuclei in the brain stem. Each of these nuclei corresponds to three cranial nerves, the facial nerve (VII), the glossopharyngeal nerve (IX), and the vagus nerve (X) and GABA is the primary inhibitory neurotransmitter involved in its functionality. All visceral afferents in the vagus and glossopharyngeal nerves first arrive in the nucleus of the solitary tract and information from the gustatory system can then be relayed to the thalamus and cortex.

Hereditary sensory and autonomic neuropathy (HSAN) or hereditary sensory neuropathy (HSN) is a condition used to describe any of the types of this disease which inhibit sensation.

A sense is a biological system used by an organism for sensation, the process of gathering information about the surroundings through the detection of stimuli. Although, in some cultures, five human senses were traditionally identified as such, many more are now recognized. Senses used by non-human organisms are even greater in variety and number. During sensation, sense organs collect various stimuli for transduction, meaning transformation into a form that can be understood by the brain. Sensation and perception are fundamental to nearly every aspect of an organism's cognition, behavior and thought.

The following outline is provided as an overview of and topical guide to the human brain:

References

- ↑ Hawkins, S. (2010). "Phonological features, auditory objects, and illusions". Journal of Phonetics. 38 (1): 60–89. doi:10.1016/j.wocn.2009.02.001.

- ↑ Bizley, J. K.; Walker, K. M. M. (2010). "Sensitivity and Selectivity of Neurons in Auditory Cortex to the Pitch, Timbre, and Location of Sounds". Neuroscientist. 16 (4): 453–469. doi:10.1177/1073858410371009. PMID 20530254. S2CID 5931412.

- ↑ Craig JC (1999). "Grating orientation as a measure of tactile spatial acuity". Somatosensory & Motor Research . 16 (3): 197–206. doi:10.1080/08990229970456. PMID 10527368.

- ↑ Stevens, Joseph C.; Alvarez-Reeves, Marty; Dipietro, Loretta; Mack, Gary W.; Green, Barry G. (September 2003). "Decline of tactile acuity in aging: a study of body site, blood flow, and lifetime habits of smoking and physical activity". Somatosensory & Motor Research. 20 (3–4): 271–279. doi:10.1080/08990220310001622997. PMID 14675966. S2CID 19729552.

- ↑ Li, X. (1976). "Acute Central Cord Syndrome Injury Mechanisms and Stress Features". Spine. 35 (19): E955–E964. doi:10.1097/brs.0b013e3181c94cb8. PMID 20543769. S2CID 36635584.

- ↑ Macaluso, E. (2010). "Orienting of spatial attention and the interplay between the senses. [Review]". Cortex. 46 (3): 282–297. doi:10.1016/j.cortex.2009.05.010. PMID 19540475. S2CID 2762445.

- 1 2 Heine, C.; Browning, C. J. (2002-01-01). "Communication and psychosocial consequences of sensory loss in older adults: overview and rehabilitation directions". Disability and Rehabilitation. 24 (15): 763–773. doi:10.1080/09638280210129162. ISSN 0963-8288. PMID 12437862. S2CID 32915734.