Mahajangasuchus is an extinct genus of crocodyliform which had blunt, conical teeth. The type species, M. insignis, lived during the Late Cretaceous; its fossils have been found in the Maevarano Formation in northern Madagascar. It was a fairly large predator, measuring up to 4 metres (13 ft) long.

Trematochampsa is a dubious extinct genus of crocodyliform from the Late Cretaceous In Beceten Formation of Niger.

Elosuchus is an extinct genus of neosuchian crocodyliform that lived during the Middle Cretaceous of what is now Africa.

Hyposaurus is a genus of extinct marine dyrosaurid crocodyliform. Fossils have been found in Paleocene aged rocks of the Iullemmeden Basin in West Africa, Campanian–Maastrichtian Shendi Formation of Sudan and Maastrichtian through Danian strata in New Jersey, Alabama and South Carolina. Isolated teeth comparable to Hyposaurus have also been found in Thanetian strata of Virginia. It was related to Dyrosaurus. The priority of the species H. rogersii has been debated, however there is no sound basis for the recognition of more than one species from North America. The other North American species are therefore considered nomina vanum.

Notosuchia is a suborder of primarily Gondwanan mesoeucrocodylian crocodylomorphs that lived during the Jurassic and Cretaceous. Some phylogenies recover Sebecosuchia as a clade within Notosuchia, others as a sister group ; if Sebecosuchia is included within Notosuchia its existence is pushed into the Middle Miocene, about 11 million years ago. Fossils have been found from South America, Africa, Asia, and Europe. Notosuchia was a clade of terrestrial crocodilians that evolved a range of feeding behaviours, including herbivory (Chimaerasuchus), omnivory (Simosuchus), and terrestrial hypercarnivory (Baurusuchus). It included many members with highly derived traits unusual for crocodylomorphs, including mammal-like teeth, flexible bands of shield-like body armor similar to those of armadillos (Armadillosuchus), and possibly fleshy cheeks and pig-like snouts (Notosuchus). The suborder was first named in 1971 by Zulma Gasparini and has since undergone many phylogenetic revisions.

Peirosauridae is a Gondwanan family of mesoeucrocodylians that lived during the Cretaceous period. It was a clade of terrestrial crocodyliforms that evolved a rather dog-like skull, and were terrestrial carnivores. It was phylogenetically defined in 2004 as the most recent common ancestor of Peirosaurus and Lomasuchinae and all of its descendants. Lomasuchinae is a subfamily of peirosaurids that includes the genus Lomasuchus.

Araripesuchus is a genus of extinct crocodyliform that existed during the Cretaceous period of the late Mesozoic era some 125 to 66 million years ago. Six species of Araripesuchus are currently known. They are generally considered to be notosuchians, characterized by their varied teeth types and distinct skull elements. This genus consists of six species: A. buitreraensis, discovered in Argentina, A. wegeneri, discovered in Cameroon and Niger, A. rattoides, discovered in Niger, A. tsangatsangana, discovered in Madagascar, A. gomesii, discovered in Brazil and another species discovered in Argentina, A. patagonicus. It has been argued that the phylogenetic position of this genus is uncertain, and that taxonomic revision is required.

Pabwehshi is an extinct genus of mesoeucrocodylian. It is based on GSP-UM 2000, a partial snout and corresponding lower jaw elements, with another snout assigned to it. These specimens were found in Maastrichtian-age Upper Cretaceous rocks of the Vitakri and Pab Formations in Balochistan, Pakistan, and represent the first diagnostic crocodyliform fossils from Cretaceous rocks of South Asia. Pabwehshi had serrated interlocking teeth in its snout that formed a "zig-zag" cutting edge. Pabwehshi was named in 2001 by Jeffrey A. Wilson and colleagues. The type species is P. pakistanensis, in reference to the nation where it was found. It was traditionally classified as a baurusuchid closely related to Cynodontosuchus and Baurusuchus. Larsson and Sues (2007) found close affinity between Pabwehshi and the Peirosauridae within Sebecia. Montefeltro et al.Pabwehshi has a sagittal torus on its maxillary palatal shelves – a character that is absent in baurusuchids – but they did not include Pabwehshi in their phylogenetic analysis.

Trematochampsidae is an extinct family of mesoeucrocodylian crocodyliforms. Fossils are present from Madagascar, Morocco, Niger, Argentina, and Brazil. Possible trematochampsids have been found from Spain and France, but classification past the family level is indeterminant. The trematochampsids first appeared during the Barremian stage of the Early Cretaceous and became extinct during the late Maastrichtian stage of the Late Cretaceous.

Armadillosuchus is an extinct genus of sphagesaurid crocodylomorph. It was described in February 2009 from the late Campanian to early Maastrichtian Adamantina Formation of the Bauru Basin in Brazil, dating to approximately 70 Ma. Armadillosuchus was among the larger and more robust sphagesaurids, with a total length of approximately 2 metres (6.6 ft).

Stolokrosuchus is an extinct genus of crocodyliforms that lived during the Early Cretaceous. Its fossils, including a skull with a long thin snout and bony knobs on the prefrontal, have been found in Niger. Stolokrosuchus was described in 2000 by Hans Larsson and Boubacar Gado. The type species is S. lapparenti. They initially described it as related to Peirosauridae, if not a member of that family. One study has shown it to be related to Elosuchus. However, more recent works usually find Stolokrosuchus to be one of the basalmost neosuchian, only distantly related to the elosuchid or pholidosaurid, Elosuchus. It was a semiaquatic crocodylomorph.

Kaprosuchus is an extinct genus of mahajangasuchid crocodyliform. It is known from a single nearly complete skull collected from the Upper Cretaceous Echkar Formation of Niger. The name means "boar crocodile" from the Greek κάπρος, kapros ("boar") and σοῦχος, soukhos ("crocodile") in reference to its unusually large caniniform teeth which resemble those of a boar. It has been nicknamed "BoarCroc" by Paul Sereno and Hans Larsson, who first described the genus in a monograph published in ZooKeys in 2009 along with other Saharan crocodyliformes such as Anatosuchus and Laganosuchus. The type species is K. saharicus.

Sebecus is an extinct genus of sebecid crocodylomorph from Eocene of South America. Like other sebecosuchians, it was entirely terrestrial and carnivorous. The genus is currently represented by two species, the type S. icaeorhinus and S. ayrampu. Several other species have been referred to Sebecus, but were later reclassified as their own genera.

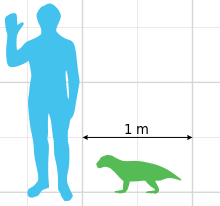

Pakasuchus is a genus of notosuchian crocodyliform distinguished by its unusual mammal-like appearance, including mammal-like teeth that would have given the animal the ability to chew. It also had long, slender legs and a doglike nose. Fossils have been found in the Galula Formation of Rukwa Rift Basin of southwestern Tanzania, and were described in 2010 in the journal Nature. Pakasuchus is originally considered to lived approximately 105 million years ago, in the mid-Cretaceous, but later age of site is reconsidered to the late Cretaceous, Cenomanian to Campanian instead. The type species is P. kapilimai. Pakasuchus means "cat crocodile" in reference to its catlike skull.

Sebecosuchia is an extinct group of mesoeucrocodylian crocodyliforms that includes the families Sebecidae and Baurusuchidae. The group was long thought to have first appeared in the Late Cretaceous with the baurusuchids and become extinct in the Miocene with the last sebecids, but Razanandrongobe pushes the origin of Sebecosuchia to the Middle Jurassic. Fossils have been found primarily from South America but have also been found in Europe, North Africa, Madagascar, and the Indian subcontinent.

Pissarrachampsa is an extinct genus of baurusuchid mesoeucrocodylian from the Late Cretaceous of Brazil. It is based on a nearly complete skull and a referred partial skull and lower jaw from the ?Campanian - ?Maastrichtian-age Vale do Rio do Peixe Formation of the Bauru Group, found in the vicinity of Gurinhatã, Brazil.

Gasparinisuchus is an extinct genus of peirosaurid notosuchian known from the Late Cretaceous of Neuquén and Mendoza Provinces, western central Argentina. It contains a single species, Gasparinisuchus peirosauroides.

Rukwasuchus is an extinct genus of peirosaurid crocodyliforms known from the middle Cretaceous Galula Formation of southwestern Tanzania. It contains a single species, Rukwasuchus yajabalijekundu.

Anthracosuchus is an extinct genus of dyrosaurid crocodyliform from the Paleocene of Colombia. Remains of Anthracosuchus balrogus, the only known species, come from the Cerrejón Formation in the Cerrejón mine, and include four fossil specimens with partial skulls. Anthracosuchus differs from other dyrosaurids in having an extremely short (brevirostrine) snout, widely spaced eye sockets with bony protuberances around them, and osteoderms that are smooth and thick. It is one of the most basal dyrosaurids along with Chenanisuchus and Cerrejonisuchus.

Barrosasuchus is a genus of peirosaurid notosuchian from the Santonian of Argentina and part of the extensive peirosaurid record of Late Cretaceous Patagonia. It contains one species, Barrosasuchus neuquenianus. B. neuquenianus is known from an almost complete skull and the majority of the articulated postcranial skeleton, making it the best preserved Patagonian peirosaurid.