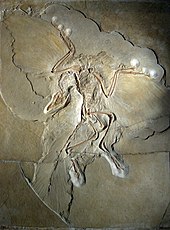

Archaeopteryx, sometimes referred to by its German name, "Urvogel" is a genus of bird-like dinosaurs. The name derives from the ancient Greek ἀρχαῖος (archaīos), meaning "ancient", and πτέρυξ (ptéryx), meaning "feather" or "wing". Between the late 19th century and the early 21st century, Archaeopteryx was generally accepted by palaeontologists and popular reference books as the oldest known bird. Older potential avialans have since been identified, including Anchiornis, Xiaotingia, and Aurornis.

Protoavis is a problematic taxon known from fragmentary remains from Late Triassic Norian stage deposits near Post, Texas. The animal's true classification has been the subject of much controversy, and there are many different interpretations of what the taxon actually is. When it was first described, the fossils were described as being from a primitive bird which, if the identification is valid, would push back avian origins some 60–75 million years.

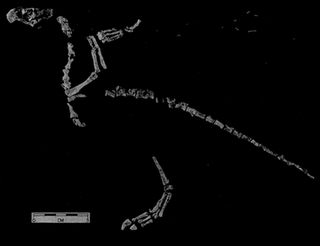

Alvarezsauridae is a family of small, long-legged dinosaurs. Although originally thought to represent the earliest known flightless birds, they are now thought to be an early diverging branch of maniraptoran theropods. Alvarezsaurids were highly specialized. They had tiny but stout forelimbs, with compact, bird-like hands. Their skeletons suggest that they had massive breast and arm muscles, possibly adapted for digging or tearing. They had long, tube-shaped snouts filled with tiny teeth. They have been interpreted as myrmecophagous, adapted to prey on colonial insects such as termites, with the short arms acting as effective digging instruments to break into nests.

Confuciusornis is a genus of basal crow-sized avialan from the Early Cretaceous Period of the Yixian and Jiufotang Formations of China, dating from 125 to 120 million years ago. Like modern birds, Confuciusornis had a toothless beak, but closer and later relatives of modern birds such as Hesperornis and Ichthyornis were toothed, indicating that the loss of teeth occurred convergently in Confuciusornis and living birds. It was thought to be the oldest known bird to have a beak, though this title now belongs to an earlier relative Eoconfuciusornis. It was named after the Chinese moral philosopher Confucius. Confuciusornis is one of the most abundant vertebrates found in the Yixian Formation, and several hundred complete specimens have been found.

The Enantiornithes, also known as enantiornithines or enantiornitheans in literature, are a group of extinct avialans, the most abundant and diverse group known from the Mesozoic era. Almost all retained teeth and clawed fingers on each wing, but otherwise looked much like modern birds externally. Over seventy species of Enantiornithes have been named, but some names represent only single bones, so it is likely that not all are valid. The Enantiornithes became extinct at the Cretaceous–Paleogene boundary, along with Hesperornithes and all other non-avian dinosaurs.

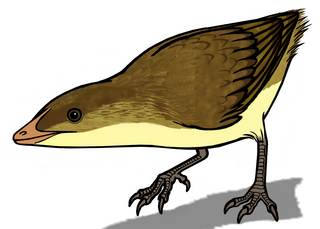

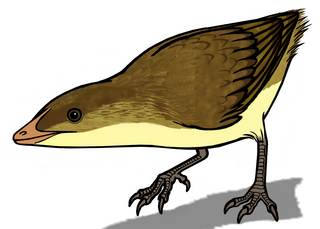

Iberomesornis is a monotypic genus of enantiornithine bird of the Cretaceous of Spain.

Jeholornis is a genus of avialan dinosaurs that lived between approximately 122 and 120 million years ago during the early Cretaceous Period in China. Fossil Jeholornis were first discovered in the Jiufotang Formation in Hebei Province, China and additional specimens have been found in the older Yixian Formation.

The scientific question of within which larger group of animals birds evolved has traditionally been called the "origin of birds". The present scientific consensus is that birds are a group of maniraptoran theropod dinosaurs that originated during the Mesozoic era.

Confuciusornithidae is an extinct family of pygostylian avialans known from the Early Cretaceous, found in northern China. They are commonly placed as a sister group to Ornithothoraces, a group that contains all extant birds along with their closest extinct relatives. Confuciusornithidae contains four genera, possessing both shafted and non-shafted (downy) feathers. Some specimens probably referable to this clade represents one of the earliest known fossil evidence of primary feather moulting. They are also noted for their distinctive pair of ribbon-like tail feathers of disputed function.

Eoalulavis is a monotypic genus of enantiornithean bird that lived during the Barremian, in the Lower Cretaceous around 125 million years ago. The only known species is Eoalulavis hoyasi.

Cathayornis is a genus of enantiornithean birds from the Jiufotang Formation of Liaoning, People's Republic of China. It is known definitively from only one species, Cathayornis yandica, one of the first Enantiornithes found in China. Several additional species were once incorrectly classified as Cathayornis, and have since been reclassified or regarded as nomina dubia.

Neuquenornis volans is a species of enantiornithean birds which lived during the late Cretaceous period in today's Patagonia, Argentina. It is the only known species of the genus Neuquenornis. Its fossils were found in the Santonian Bajo de la Carpa Formation, dating from about 85-83 million years ago. This was a sizeable bird for its time, with a tarsometatarsus 46.8mm long. Informal estimates suggest that it measured nearly 30 cm (12 in) in length excluding the tail.

Ornithothoraces is a group of avialan dinosaurs that includes all enantiornithes and the euornithes, which includes modern birds and their closest ancestors. The name Ornithothoraces means "bird thoraxes". This refers to the modern, highly advanced anatomy of the thorax that gave the ornithothoracines superior flight capability compared with more primitive avialans. This anatomy includes a large, keeled breastbone, elongated coracoids and a modified glenoid joint in the shoulder, and a semi-rigid rib cage. In spite of this at least the sternum seems to have developed convergently rather than being a true homology.

The proximodorsal process is a feature of the skeleton of archosaurs. It may be a pair of tabs or blade - shaped flanges on the pelvis, and serves as an anchor point for the attachment of leg muscles. This process is of particular importance in the anatomy and comparative morphology of Mesozoic birds and advanced maniraptoran dinosaurs. The pelvis is made up of three paired bones and a sacrum. The three paired bones are called the ilium, the ischium, and the pubis. On the ischium there may be an obturator process and/or a proximodorsal process. The more primitive condition is for there to be no proximodorsal process, but a large obturator process. In primitive birds the ischia are complex, usually with a small or even absent obturator process and a large, rectangular, proximodorsal process extending up toward the ilium. This is the condition in Archaeopteryx, Confuciusornis, and enantiornithines. The South American dromaeosaurs called the unenlagiinae have an intermediate condition between the two, with both a large obturator process and a proximodorsal process.

Avisauridae is a family of extinct enantiornithine dinosaurs from the Cretaceous period, distinguished by several features of their ankle bones. Depending on the definition used, Avisauridae is either a broad and widespread group of advanced enantiornithines, or a small family within that group, restricted to species from the Late Cretaceous of North and South America.

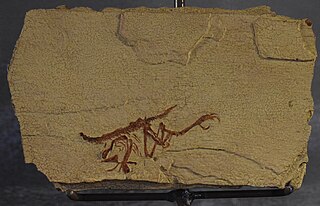

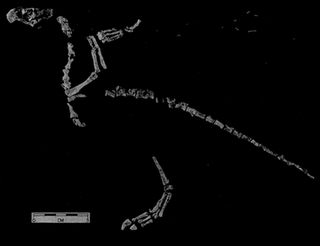

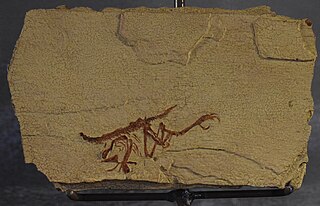

Shanweiniao is a genus of long-snouted enantiornithean birds from Early Cretaceous China. One species is known, Shanweiniao cooperorum. There is one known fossil, a slab and counterslab. The fossil is in the collection of the Dalian Natural History Museum, and has accession number DNHM D1878/1 and DNHM1878/2. It was collected from the Lower Cretaceous Dawangzhengzi Beds, middle Yixian Formation, from Lingyuan in the Liaoning Province, China.

Longipterygidae is a family of early enantiornithean avialans from the Early Cretaceous epoch of China. All known specimens come from the Jiufotang Formation and Yixian Formation, dating to the early Aptian age, 125-120 million years ago.

Aurornis is an extinct genus of anchiornithid theropod dinosaurs from the Jurassic period of China. The genus Aurornis contains a single known species, Aurornis xui. Aurornis xui may be the most basal ("primitive") avialan dinosaur known to date, and it is one of the earliest avialans found to date. The fossil evidence for the animal pre-dates that of Archaeopteryx lithographica, often considered the earliest bird species, by about 10 million years.

Houornis is a genus of enantiornithean birds from the Jiufotang Formation of Liaoning, People's Republic of China. It is known from a single species, Houornis caudatus, which had been once been classified as a species of Cathayornis, and has also been regarded as a nomen dubium.

Jianianhualong is a genus of troodontid theropod dinosaur from the Early Cretaceous of China. It contains a single species, Jianianhualong tengi, named in 2017 by Xu Xing and colleagues based on an articulated skeleton preserving feathers. The feathers at the middle of the tail of Jianianhualong are asymmetric, being the first record of asymmetrical feathers among the troodontids. Despite aerodynamic differences from the flight feathers of modern birds, the feathers in the tail vane of Jianianhualong could have functioned in drag reduction whilst the animal was moving. The discovery of Jianianhualong supports the notion that asymmetrical feathers appeared early in the evolutionary history of the Paraves.