The history of Spain dates to contact between the pre-Roman peoples of the Mediterranean coast of the Iberian Peninsula made with the Greeks and Phoenicians. During Classical Antiquity, the peninsula was the site of multiple successive colonizations of Greeks, Carthaginians, and Romans. Native peoples of the peninsula, such as the Tartessos people, intermingled with the colonizers to create a uniquely Iberian culture. The Romans referred to the entire peninsula as Hispania, from which the name "Spain" originates. As was the rest of the Western Roman Empire, Spain was subject to the numerous invasions of Germanic tribes during the 4th and 5th centuries AD, resulting in the end of Roman rule and the establishment of Germanic kingdoms, marking the beginning of the Middle Ages in Spain.

Philip II, also known as Philip the Prudent, was King of Spain from 1556, King of Portugal from 1580, and King of Naples and Sicily from 1554 until his death in 1598. He was also jure uxoris King of England and Ireland from his marriage to Queen Mary I in 1554 until her death in 1558. He was also Duke of Milan from 1540. From 1555, he was Lord of the Seventeen Provinces of the Netherlands.

Philip III was King of Spain. As Philip II, he was also King of Portugal, Naples, Sicily and Sardinia and Duke of Milan from 1598 until his death in 1621.

Philip IV, also called the Planet King, was King of Spain from 1621 to his death and King of Portugal from 1621 to 1640. Philip is remembered for his patronage of the arts, including such artists as Diego Velázquez, and his rule over Spain during the Thirty Years' War.

Joanna, historically known as Joanna the Mad, was the nominal queen of Castile from 1504 and queen of Aragon from 1516 to her death in 1555. She was the daughter of Queen Isabella I of Castile and King Ferdinand II of Aragon. Joanna was married by arrangement to the Austrian archduke Philip the Handsome on 20 October 1496. Following the deaths of her elder brother John, elder sister Isabella, and nephew Miguel between 1497 and 1500, Joanna became the heir presumptive to the crowns of Castile and Aragon. When her mother died in 1504, she became queen of Castile. Her father proclaimed himself governor and administrator of Castile.

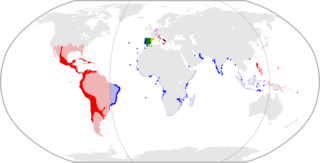

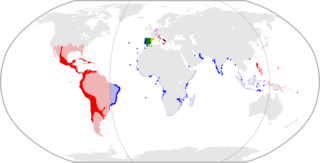

The Spanish Empire, sometimes referred to as the Hispanic Monarchy or the Catholic Monarchy, was a colonial empire that existed between 1492 and 1976. In conjunction with the Portuguese Empire, it ushered in the European Age of Discovery. It achieved a global scale, controlling vast portions of the Americas, Africa, various islands in Asia and Oceania, as well as territory in other parts of Europe. It was one of the most powerful empires of the early modern period, becoming known as "the empire on which the sun never sets". At its greatest extent in the late 1700s and early 1800s, the Spanish Empire covered over 13 million square kilometres, making it one of the largest empires in history.

The Catholic Monarchs were Queen Isabella I of Castile and King Ferdinand II of Aragon, whose marriage and joint rule marked the de facto unification of Spain. They were both from the House of Trastámara and were second cousins, being both descended from John I of Castile; to remove the obstacle that this consanguinity would otherwise have posed to their marriage under canon law, they were given a papal dispensation by Sixtus IV. They married on October 19, 1469, in the city of Valladolid; Isabella was 18 years old and Ferdinand a year younger. It is generally accepted by most scholars that the unification of Spain can essentially be traced back to the marriage of Ferdinand and Isabella. Their reign was called by W.H. Prescott "the most glorious epoch in the annals of Spain".

Habsburg Spain refers to Spain and the Spanish Empire, also known as the Catholic Monarchy, in the period from 1516 to 1700 when it was ruled by kings from the House of Habsburg. It had territories around the world, including modern-day Spain, a piece of south-eastern France, eventually Portugal and many other lands outside the Iberian Peninsula, like in the Americas. Habsburg Spain was a composite monarchy and a personal union. The Habsburg Spanish monarchs of this period are chiefly Charles I, Philip II, Philip III, Philip IV and Charles II. In this period the Spanish empire was at the zenith of its influence and power. Spain, or "the Spains", referring to Spanish territories across different continents in this period, initially covered the entire Iberian peninsula, including the crowns of Castile, Aragon and from 1580 Portugal. It then expanded to include territories over the five continents, consisting of much of the American continent and islands thereof, the West Indies in the Americas, the Low Countries, Belgium, Luxembourg, Italian territories and France in Europe, Portuguese possessions such as small enclaves like Ceuta and Oran in North Africa, and the Philippines and other possessions in Southeast Asia. The period of Spanish history has also been referred to as the "Age of Expansion".

The Iberian Union is a historiographical term used to describe the dynastic union of the Monarchy of Spain, which in turn was itself a dynastic union of the crowns of Castile and Aragon, and the Kingdom of Portugal, and of their respective colonial empires, that existed between 1580 and 1640 and brought the entire Iberian Peninsula except Andorra, as well as Portuguese and Spanish overseas possessions, under the Spanish Habsburg monarchs Philip II, Philip III, and Philip IV. The union began after the Portuguese crisis of succession and the ensuing War of the Portuguese Succession, and lasted until the Portuguese Restoration War, during which the House of Braganza was established as Portugal's new ruling dynasty with the acclamation of John IV as the new King of Portugal.

The Principality of Catalonia was a medieval and early modern state in the northeastern Iberian Peninsula. During most of its history it was in dynastic union with the Kingdom of Aragon, constituting together the Crown of Aragon. Between the 13th and the 18th centuries, it was bordered by the Kingdom of Aragon to the west, the Kingdom of Valencia to the south, the Kingdom of France and the feudal lordship of Andorra to the north and by the Mediterranean Sea to the east. The term Principality of Catalonia was official until the 1830s, when the Spanish government implemented the centralized provincial division, but remained in popular and informal contexts. Today, the term Principat (Principality) is used primarily to refer to the autonomous community of Catalonia in Spain, as distinct from the other Catalan Countries, and usually including the historical region of Roussillon in Southern France.

The Reapers' War, also known as the Catalan Revolt, was a conflict that affected the Principality of Catalonia between the years of 1640 and 1659. It had an enduring effect in the Treaty of the Pyrenees (1659), which ceded the County of Roussillon and the northern half of the County of Cerdanya to France, splitting these northern Catalan territories off from the Principality of Catalonia and the Crown of Aragon, and thereby receding the borders of Spain to the Pyrenees.

The Crown of Castile was a medieval polity in the Iberian Peninsula that formed in 1230 as a result of the third and definitive union of the crowns and, some decades later, the parliaments of the kingdoms of Castile and León upon the accession of the then Castilian king, Ferdinand III, to the vacant Leonese throne. It continued to exist as a separate entity after the personal union in 1469 of the crowns of Castile and Aragon with the marriage of the Catholic Monarchs up to the promulgation of the Nueva Planta decrees by Philip V in 1715.

The Franco-Spanish War was fought from 1635 to 1659 between France and Spain, each supported by various allies at different points. The first phase, beginning in May 1635 and ending with the 1648 Peace of Westphalia, is considered a related conflict of the Thirty Years' War. The second phase continued until 1659, when France and Spain agreed to peace terms in the Treaty of the Pyrenees.

The early modern period in Catalan literature and historiography, while extremely productive for Castilian writers of the Siglo de Oro, has been termed La Decadència, an era of decadence in Catalan literature and history, generally thought to be caused by a general falling into disuse of the vernacular language in cultural contexts and lack of patronage among the nobility, even in lands of the Crown of Aragon. This decadence is thought to accompany the general Castilianization of Spain and overall neglect of the Crown of Aragon's institutions after the dynastic union of the crowns of Castile and Aragon that resulted from the marriage of Ferdinand II of Aragon and Isabella I of Castile, a union finalized in 1474.

Roberto de Zúñiga y Velasco was a Spanish royal favourite of Philip III, his son Philip IV and a key minister in two Spanish governments. In control of foreign policy from 1618 to 1622, he was responsible for Spain's initially successful entry into the Thirty Years War (1618–1648) and for the appointment of his nephew, the Count-Duke of Olivares to the position of prime minister for much of the reign of Philip IV. De Zúñiga was also notable as being one of the very few Spanish royal favourites of the period to die whilst still in favour.

Gaspar de Guzmán y Pimentel, 1st Duke of Sanlúcar, 3rd Count of Olivares,, known as the Count-Duke of Olivares, was a Spanish royal favourite of Philip IV and minister. Appointed as Grandee on 10 April 1621, a day after the ending of the Twelve Years' Truce to January 1643, he over-exerted Spain in foreign affairs and unsuccessfully attempted domestic reform. His policy of committing Spain to recapture Holland led to a renewal of the Eighty Years' War while Spain was also embroiled in the Thirty Years' War (1618–1648). In addition, his attempts to centralise power and increase wartime taxation led to revolts in Catalonia and in Portugal, which brought about his downfall.

The Council of Aragon, officially, the Royal and Supreme Council of Aragon, was a ruling body and key part of the domestic government of the Spanish Empire in Europe, second only to the monarch himself. It administered the Crown of Aragon, which was composed of the Kingdom of Aragon, Principality of Catalonia, Kingdom of Valencia, Kingdom of Mallorca, and finally the Kingdom of Sardinia. The Aragonese possessions in Southern Italy were later incorporated into the Council of Italy, together with the Duchy of Milan, in 1556. The Council of Aragon ruled these territories as a part of Spain, and later the Iberian Union.

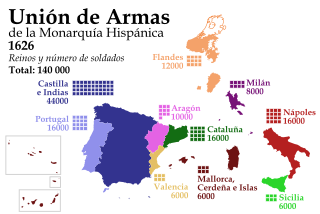

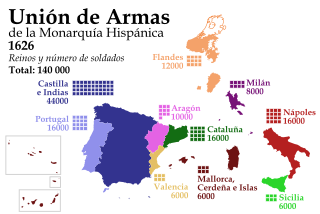

The Union of Arms was a political proposal, put forward by Gaspar de Guzmán, Count-Duke of Olivares for greater military co-operation between the constituent parts of the composite monarchy ruled by Philip IV of Spain.

The Kingdom of Spain entered a new era with the death of Charles II, the last Spanish Habsburg monarch, who died childless in 1700. The War of the Spanish Succession was fought between proponents of a Bourbon prince, Philip of Anjou, and the Austrian Habsburg claimant, Archduke Charles. After the wars were ended with the Peace of Utrecht, Philip V's rule began in 1715, although he had to renounce his place in the succession of the French throne.

The Spanish Decadence was the gradual process of exhaustion and attrition suffered by the Spanish Monarchy throughout the 17th century, during the reigns of the so-called minor Habsburgs ; a historical process simultaneous to the so-called general crisis of the 17th century, but which was especially serious for Spain, to such an extent that it went from being the hegemonic power in Europe and the largest economy in the world in the 17th century to becoming an impoverished and semi-peripheral country.