Notes and references

Notes

- ↑ According to Fullerton et al. 2012 , pp. 281–292: "...sporadic cases do not necessarily share a single specific common contaminated source..."

Related Research Articles

Dengue fever is a mosquito-borne tropical disease caused by dengue virus. It is frequently asymptomatic; if symptoms appear they typically begin 3 to 14 days after infection. These may include a high fever, headache, vomiting, muscle and joint pains, and a characteristic skin itching and skin rash. Recovery generally takes two to seven days. In a small proportion of cases, the disease develops into severe dengue with bleeding, low levels of blood platelets, blood plasma leakage, and dangerously low blood pressure.

Dysentery, historically known as the bloody flux, is a type of gastroenteritis that results in bloody diarrhea. Other symptoms may include fever, abdominal pain, and a feeling of incomplete defecation. Complications may include dehydration.

An epidemic is the rapid spread of disease to a large number of hosts in a given population within a short period of time. For example, in meningococcal infections, an attack rate in excess of 15 cases per 100,000 people for two consecutive weeks is considered an epidemic.

Epidemiology is the study and analysis of the distribution, patterns and determinants of health and disease conditions in a defined population.

Shigellosis is an infection of the intestines caused by Shigella bacteria. Symptoms generally start one to two days after exposure and include diarrhea, fever, abdominal pain, and feeling the need to pass stools even when the bowels are empty. The diarrhea may be bloody. Symptoms typically last five to seven days and it may take several months before bowel habits return entirely to normal. Complications can include reactive arthritis, sepsis, seizures, and hemolytic uremic syndrome.

Shigella is a genus of bacteria that is Gram-negative, facultatively anaerobic, non–spore-forming, nonmotile, rod-shaped, and is genetically closely related to Escherichia. The genus is named after Kiyoshi Shiga, who discovered it in 1897.

In epidemiology, an outbreak is a sudden increase in occurrences of a disease when cases are in excess of normal expectancy for the location or season. It may affect a small and localized group or impact upon thousands of people across an entire continent. The number of cases varies according to the disease-causing agent, and the size and type of previous and existing exposure to the agent. Outbreaks include many epidemics, which term is normally only for infectious diseases, as well as diseases with an environmental origin, such as a water or foodborne disease. They may affect a region in a country or a group of countries. Pandemics are near-global disease outbreaks when multiple and various countries around the Earth are soon infected.

In epidemiology, an infection is said to be endemic in a specific population or populated place when that infection is constantly present, or maintained at a baseline level, without extra infections being brought into the group as a result of travel or similar means. The term describes the distribution (spread) of an infectious disease among a group of people or within a populated area. An endemic disease always has a steady, predictable number of people getting sick, but that number can be high (hyperendemic) or low (hypoendemic), and the disease can be severe or mild. Also, a disease that is usually endemic can become epidemic.

Bacillary dysentery is a type of dysentery, and is a severe form of shigellosis. It is associated with species of bacteria from the family Enterobacteriaceae. The term is usually restricted to Shigella infections.

Disease surveillance is an epidemiological practice by which the spread of disease is monitored in order to establish patterns of progression. The main role of disease surveillance is to predict, observe, and minimize the harm caused by outbreak, epidemic, and pandemic situations, as well as increase knowledge about which factors contribute to such circumstances. A key part of modern disease surveillance is the practice of disease case reporting.

Bangladesh is one of the most populous countries in the world, as well as having one of the fastest growing economies in the world. Consequently, Bangladesh faces challenges and opportunities in regards to public health. A remarkable metamorphosis has unfolded in Bangladesh, encompassing the demographic, health, and nutritional dimensions of its populace.

The International Vaccine Institute (IVI) is an independent, nonprofit, international organization founded on the belief that the health of children in developing countries can be dramatically improved by the use of new and improved vaccines. Working in collaboration with the international scientific community, public health organizations, governments, and industry, IVI is involved in all areas of the vaccine spectrum – from new vaccine design in the laboratory to vaccine development and evaluation in the field to facilitating sustainable introduction of vaccines in countries where they are most needed.

As of 2010, dengue fever is believed to infect 50 to 100 million people worldwide a year with 1/2 million life-threatening infections. It dramatically increased in frequency between 1960 and 2010, by 30 fold. This increase is believed to be due to a combination of urbanization, population growth, increased international travel, and global warming. The geographical distribution is around the equator with 70% of the total 2.5 billion people living in endemic areas from Asia and the Pacific. Many of the infected people during outbreaks are not virally tested, therefore their infections may also be due to chikungunya, a coinfection of both, or even other similar viruses.

In the 2015 dengue outbreak in Taiwan, a significant rise in the number of dengue fever cases was reported in Tainan City, Kaohsiung City, and Pingtung City. As of the end of 2015, official data showed that more than 40,000 people, mostly in these three cities, were infected in 2015. This epidemic began in the summer of 2015, with the first reported occurrence in the North District, Tainan. There were several documented cases in other cities and counties but none resulted in death or were of such large scale.

The Norwegian Institute of Public Health is responsible for maintaining and revising the list of notifiable diseases in Norway and participates in the European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control (ECDC) and the World Health Organization's surveillance of infectious diseases. The notifiable diseases are classified into Group A, Group B and Group C diseases, depending on the procedure for reporting the disease.

Neil Morris Ferguson is a British epidemiologist and professor of mathematical biology, who specialises in the patterns of spread of infectious disease in humans and animals. He is the director of the Jameel Institute, and of the MRC Centre for Global Infectious Disease Analysis, and head of the Department of Infectious Disease Epidemiology in the School of Public Health and Vice-Dean for Academic Development in the Faculty of Medicine, all at Imperial College London.

In epidemiology, particularly in the discussion of infectious disease dynamics (modeling), the latent period is the time interval between when an individual or host is infected by a pathogen and when that individual becomes infectious, i.e. capable of transmitting pathogens to other susceptible individuals.

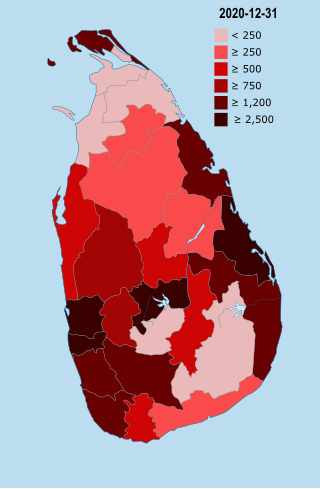

The dengue pandemic in Sri Lanka is part of the tropical disease dengue fever pandemic. Dengue fever is caused by Dengue virus, first recorded in the 1960s. It is not a native disease in this island. Present-day dengue has become a major public health problem. Aedes aegypti and Aedes albopictus are both mosquito species native to Sri Lanka. However, the disease did not emerge until the early 1960s. Dengue was first serologically confirmed in the country in 1962. A Chikungunya outbreak followed in 1965. In the early 1970s two type of dengue dominated in Sri Lanka: DENV-1 type1 and DENV-2 type 2. A total of 51 cases and 15 deaths were reported in 1965–1968. From 1989 onward, dengue fever has become endemic in Sri Lanka.

In epidemiology, the term hyperendemic disease is used to refer to a disease which is constantly and persistently present in a population at a high rate of incidence and/or prevalence (occurrence) and which equally affects all age groups of that population. It is one of the various degrees of endemicity.

COVID-19 is predicted to become an endemic disease by many experts. The observed behavior of SARS-CoV-2, the virus that causes COVID-19, suggests it is unlikely it will die out, and the lack of a COVID-19 vaccine that provides long-lasting immunity against infection means it cannot immediately be eradicated; thus, a future transition to an endemic phase appears probable. In an endemic phase, people would continue to become infected and ill, but in relatively stable numbers. Such a transition may take years or decades. Precisely what would constitute an endemic phase is contested.

References

- ↑ Miller-Keane Encyclopedia and Dictionary of Medicine, Nursing, and Allied Health (7th ed.), Saunders, 2003

- ↑ Principles of Epidemiology in Public Health Practice (3rd ed.), U.S. Department of Health and Human Services and Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), 2006, p. 72

- ↑ Miquel Porta; John M. Last, eds. (2018), A Dictionary of Public Health (2nd ed.), Oxford University Press

- ↑ Miquel Porta, ed. (2016), A Dictionary of Epidemiology (6th ed.), Oxford University Press, pp. 46–47

- ↑ "Definition of sporadic cancer". cancer.gov. National Cancer Institute. Retrieved 25 March 2024.

- ↑ "Disease and Epidemiology", Microbiology by OpenStax, XanEdu Publishing Inc, 2016, p. 699

- ↑ WHO Malaria Terminology, World Health Organization, 2019, p. 30

- ↑ Hyunjoo Pai (March 2020), "History and Epidemiology of Bacillary Dysentery in Korea: from Korean War to 2017", Infection and Chemotherapy, 52 (1): 123–131, doi: 10.3947/ic.2020.52.1.123 , PMC 7113447 , PMID 32239814, S2CID 214772371

- 1 2 Sifat Sharmin, Elvina Viennet, Kathryn Glass and David Harley (September 2015), "The emergence of dengue in Bangladesh: Epidemiology, challenges and future disease risk", Transactions of the Royal Society of Tropical Medicine and Hygiene

{{citation}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ↑ Mohammed A. Mamun; Jannatul Mawa Misti; Mark D. Griffiths; David Gozal (December 14, 2019), "The dengue epidemic in Bangladesh: risk factors and actionable items", The Lancet, 394 (10215): 2149–2150, doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(19)32524-3 , PMID 31839186, S2CID 209333186

- ↑ Lee W Riley (July 2019), "Differentiating Epidemic from Endemic or Sporadic Infectious Disease Occurrence", Microbiology Specrum, 7 (4)