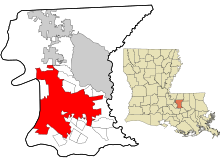

Baton Rouge is the capital city of the U.S. state of Louisiana. Located on the eastern bank of the Mississippi River, it had a population of 227,470 as of 2020; it is the seat of Louisiana's most populous parish (county-equivalent), East Baton Rouge Parish, and the center of Louisiana's second-largest metropolitan area and city, Greater Baton Rouge.

West Baton Rouge Parish is one of the sixty-four parishes in the U.S. state of Louisiana. Established in 1807, its parish seat is Port Allen. With a 2020 census population of 27,199 residents, West Baton Rouge Parish is part of the Baton Rouge metropolitan statistical area.

East Baton Rouge Parish is the most populous parish in the U.S. state of Louisiana. Its population was 456,781 at the 2020 census. The parish seat is Baton Rouge, Louisiana's state capital. East Baton Rouge Parish is located within the Greater Baton Rouge area.

Ascension Parish is a parish located in the U.S. state of Louisiana. As of the 2020 census, the population was 126,500. Its parish seat is Donaldsonville. The parish was created in 1807. Ascension Parish is part of the Baton Rouge metropolitan statistical area.

St. Gabriel is a city in Iberville Parish, Louisiana, United States. The city of St. Gabriel includes the Carville neighborhood and portions of Sunchine. Part of the Baton Rouge metropolitan statistical area, it had a population of 6,677 at the 2010 U.S. census, and 6,433 at the 2020 census.

Denham Springs is a city in Livingston Parish, Louisiana, United States. The 2010 U.S. census placed the population at 10,215, up from 8,757 at the 2000 U. S. census. At the 2020 United States census, 9,286 people lived in the city. The city is the largest area of commercial and residential development in Livingston Parish. Denham Springs and Walker are the only parish municipalities classified as cities. The area has been known as Amite Springs, Hill's Springs, and Denham Springs.

Springfield is a town in Livingston Parish, Louisiana, United States. The population was 487 at the 2010 census. It is part of the Baton Rouge metropolitan statistical area.

The Diocese of Baton Rouge, is a Latin Church ecclesiastical territory or diocese in the Florida Parishes region of the U.S. state of Louisiana. It is a suffragan in the ecclesiastical province of the Metropolitan Archdiocese of New Orleans. The current bishop is Michael Duca.

The Republic of West Florida, officially the State of Florida, was a short-lived republic in the western region of Spanish West Florida for just over 2+1⁄2 months during 1810. It was annexed and occupied by the United States later in 1810; it subsequently became part of Eastern Louisiana.

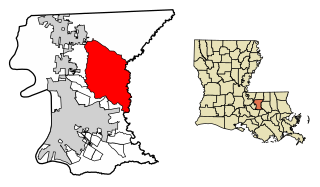

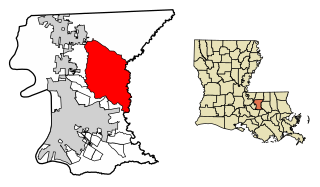

Central is a city in the U.S. state of Louisiana, third largest city in East Baton Rouge Parish, and part of the Baton Rouge metropolitan statistical area. Central had a 2020 census population of 29,565.

Louisiana Highway 22 (LA 22) is a state highway located in southeastern Louisiana. It runs 71.15 miles (114.50 km) in a general east–west direction from the junction of LA 75 and LA 942 in Darrow to U.S. Highway 190 (US 190) in Mandeville.

Interstate 55 (I-55) is a part of the Interstate Highway System that spans 964.25 miles (1,551.81 km) from LaPlace, Louisiana, to Chicago, Illinois. Within the state of Louisiana, the highway travels 66 miles (106 km) from the national southern terminus at I-10 in LaPlace to the Mississippi state line north of Kentwood.

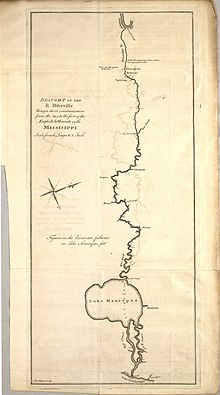

Bayou Manchac is an 18-mile-long (29 km) bayou in southeast Louisiana, USA. First called the Iberville River by its French discoverers, the bayou was once a very important waterway linking the Mississippi River to the Amite River. East Baton Rouge Parish lies on its northern side, while its southern side is divided between Ascension Parish and Iberville Parish. The large unincorporated community of Prairieville and the city of St. Gabriel both lie on its southern side.

Louisiana Highway 73 is a state highway in Louisiana stretching from Geismar to Baton Rouge. LA 73 was built as a bypass to the backbends of River Road. It was soon after bypassed itself in a more complete way with U.S. Route 61.

U.S. Highway 51 (US 51) is a part of the United States Numbered Highway System that spans 1,277 miles (2,055 km) from LaPlace, Louisiana to a point north of Hurley, Wisconsin. Within the state of Louisiana, the highway travels 69.12 miles (111.24 km) from the national southern terminus at US 61 in LaPlace to the Mississippi state line north of Kentwood.

Carlos Louis Boucher De Grand Pré was Spanish governor of the Baton Rouge district (1799–1808) and of Spanish West Florida (1805), as well as brevet colonel in the Spanish Army. He also served as lieutenant governor of Red River District and of the Natchez District.

Highland Road Community Park or Highland Road Park, is a 144.4-acre (0.584 km2) public park in Baton Rouge, Louisiana. The Recreation and Park Commission for the Parish of East Baton Rouge (BREC) owns and operates the park.

Galveztown, or Villa de Gálvez, is a ghost town located at the confluence of Bayou Manchac and the Amite River in Ascension Parish, Louisiana. Galveztown was established in 1778 with the settlement of Canary Islanders colonists and Anglo-Americans fleeing the American Revolutionary War. Due to deplorable conditions and disease, the settlement was eventually abandoned and many residents fled to Spanish Town in 1806. Some former residents remained in the area and established the community of Gálvez, Louisiana during the first half of the nineteenth century.