Bauxite is a sedimentary rock with a relatively high aluminium content. It is the world's main source of aluminium and gallium. Bauxite consists mostly of the aluminium minerals gibbsite (Al(OH)3), boehmite (γ-AlO(OH)) and diaspore (α-AlO(OH)), mixed with the two iron oxides goethite (FeO(OH)) and haematite (Fe2O3), the aluminium clay mineral kaolinite (Al2Si2O5(OH)4) and small amounts of anatase (TiO2) and ilmenite (FeTiO3 or FeO.TiO2). Bauxite appears dull in luster and is reddish-brown, white, or tan.

Karst is a topography formed from the dissolution of soluble carbonate rocks such as limestone, dolomite, and gypsum. It is characterized by features like poljes above and drainage systems with sinkholes and caves underground. More weathering-resistant rocks, such as quartzite, can also occur, given the right conditions.

A sinkhole is a depression or hole in the ground caused by some form of collapse of the surface layer. The term is sometimes used to refer to doline, enclosed depressions that are also known as shakeholes, and to openings where surface water enters into underground passages known as ponor, swallow hole or swallet. A cenote is a type of sinkhole that exposes groundwater underneath. Sink and stream sink are more general terms for sites that drain surface water, possibly by infiltration into sediment or crumbled rock.

The Dinaric Alps, also Dinarides, are a mountain range in Southern and Southcentral Europe, separating the continental Balkan Peninsula from the Adriatic Sea. They stretch from Italy in the northwest through Slovenia, Croatia, Bosnia and Herzegovina, Serbia, Montenegro, and Kosovo to Albania in the southeast.

The Coonawarra wine region is a wine region centred on the town of Coonawarra in the Limestone Coast zone of South Australia. It is known for the Cabernet Sauvignon wines produced on its "terra rossa" soil. The name has been said to have originated in Bindjali, an Aboriginal language, meaning "wild honeysuckle". It is about 380 kilometres (240 mi) south-east of Adelaide, close to the border with Victoria.

Dolomite (also known as dolomite rock, dolostone or dolomitic rock) is a sedimentary carbonate rock that contains a high percentage of the mineral dolomite, CaMg(CO3)2. It occurs widely, often in association with limestone and evaporites, though it is less abundant than limestone and rare in Cenozoic rock beds (beds less than about 66 million years in age). The first geologist to distinguish dolomite from limestone was Déodat Gratet de Dolomieu; a French mineralogist and geologist whom it is named after. He recognized and described the distinct characteristics of dolomite in the late 18th century, differentiating it from limestone.

Caliche is a sedimentary rock, a hardened natural cement of calcium carbonate that binds other materials—such as gravel, sand, clay, and silt. It occurs worldwide, in aridisol and mollisol soil orders—generally in arid or semiarid regions, including in central and western Australia, in the Kalahari Desert, in the High Plains of the western United States, in the Sonoran Desert, Chihuahuan Desert and Mojave Desert of North America, and in eastern Saudi Arabia at Al-Hasa. Caliche is also known as calcrete or kankar. It belongs to the duricrusts. The term caliche is borrowed from Spanish and is originally from the Latin word calx, meaning lime.

Rendzina is a soil type recognized in various soil classification systems, including those of Britain and Germany as well as some obsolete systems. They are humus-rich shallow soils that are usually formed from carbonate- or occasionally sulfate-rich parent material. Rendzina soils are often found in karst and mountainous regions.

Orjen is a transboundary Dinaric Mediterranean limestone mountain range, located between southernmost Bosnia and Herzegovina and southwestern Montenegro.

A polje, also called karst polje or karst field, is a large flat plain found in karstic geological regions of the world, with areas usually in the range of 5–400 km2 (2–154 sq mi). The name derives from the Slavic languages, where polje literally means 'field', whereas in English polje specifically refers to a karst plain or karst field.

A calanque is a narrow, steep-walled inlet that is developed in limestone, dolomite, or other carbonate strata and found along the Mediterranean coast. A calanque is a steep-sided valley formed within karstic regions either by fluvial erosion or the collapse of the roof of a cave that has been subsequently partially submerged by a rise in sea level.

Calcareous is an adjective meaning "mostly or partly composed of calcium carbonate", in other words, containing lime or being chalky. The term is used in a wide variety of scientific disciplines.

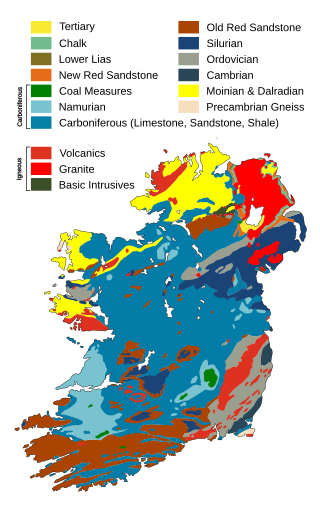

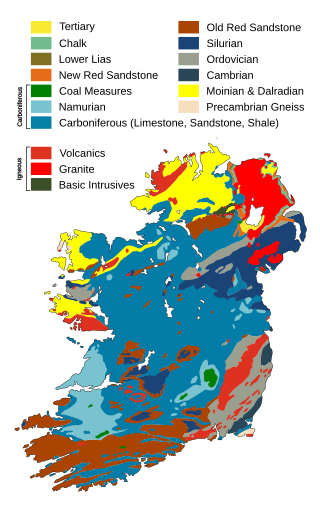

The geology of Ireland consists of the study of the rock formations on the island of Ireland. It includes rocks from every age from Proterozoic to Holocene and a large variety of different rock types is represented. The basalt columns of the Giant's Causeway together with geologically significant sections of the adjacent coast have been declared a World Heritage Site. The geological detail follows the major events in Ireland's past based on the geological timescale.

The Altopiano delle Murge is a karst topographic plateau of rectangular shape in southern Italy. Most of it lies within Puglia and corresponds with the sub-region known as Murgia or Le Murge. The plateau lies mainly in the Metropolitan City of Bari and the province of Barletta-Andria-Trani, but extends into the provinces of Brindisi and Taranto to the south, and into Matera in Basilicata to the west. The name is believed to originate from the Latin: murex, meaning 'sharp stone'.

Monte San Giorgio is a Swiss mountain and UNESCO World Heritage Site near the border between Switzerland and Italy. It is part of the Lugano Prealps, overlooking Lake Lugano in the Swiss Canton of Ticino.

Dan Hardy Yaalon was an Israeli pedologist and soil scientist, who contributed to the fields of arid and Mediterranean pedology and paleopedology, as well as the history, sociology, and philosophy of soil science. Through a research career spanning over six decades (1950–2014), Yaalon was an active member of the International Union for Quaternary Research (INQUA) and the International Soil Science Society. He was awarded the Sarton Medal for his contribution to the history of science, and the Dokuchaev Award.

The geology of Lebanon remains poorly studied prior to the Jurassic. The country is heavily dominated by limestone, sandstone, other sedimentary rocks, and basalt, defined by its tectonic history. In Lebanon, 70% of exposed rocks are limestone karst.

The geology of Croatia has some Precambrian rocks mostly covered by younger sedimentary rocks and deformed or superimposed by tectonic activity.

The geology of Saudi Arabia includes Precambrian igneous and metamorphic basement rocks, exposed across much of the country. Thick sedimentary sequences from the Phanerozoic dominate much of the country's surface and host oil.