Tzeltal or Tseltal is a Mayan language spoken in the Mexican state of Chiapas, mostly in the municipalities of Ocosingo, Altamirano, Huixtán, Tenejapa, Yajalón, Chanal, Sitalá, Amatenango del Valle, Socoltenango, Las Rosas, Chilón, San Juan Cancuc, San Cristóbal de las Casas and Oxchuc. Tzeltal is one of many Mayan languages spoken near this eastern region of Chiapas, including Tzotzil, Chʼol, and Tojolabʼal, among others. There is also a small Tzeltal diaspora in other parts of Mexico and the United States, primarily as a result of unfavorable economic conditions in Chiapas.

Goemai is an Afro-Asiatic language spoken in the Great Muri Plains region of Plateau State in central Nigeria, between the Jos Plateau and Benue River. Goemai is also the name of the ethnic group of speakers of the Goemai language. The name 'Ankwe' has been used to refer to the people, especially in older literature and to outsiders. As of 2020, it is estimated that there are around 380,000 Goemai speakers.

Araki is a nearly extinct language spoken in the small island of Araki, south of Espiritu Santo Island in Vanuatu. Araki is gradually being replaced by Tangoa, a language from a neighbouring island.

Southern Oromo, or Borana, is a variety of Oromo spoken in southern Ethiopia and northern Kenya by the Borana people. Günther Schlee also notes that it is the native language of a number of related peoples, such as the Sakuye.

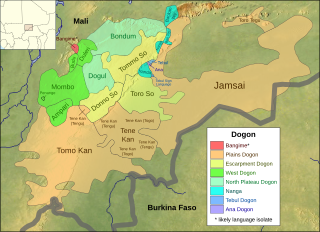

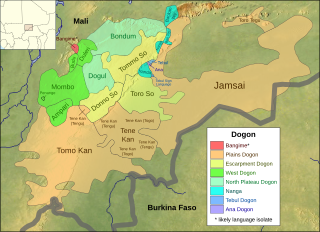

Bangime is a language isolate spoken by 3,500 ethnic Dogon in seven villages in southern Mali, who call themselves the bàŋɡá–ndɛ̀. Bangande is the name of the ethnicity of this community and their population grows at a rate of 2.5% per year. The Bangande consider themselves to be Dogon, but other Dogon people insist they are not. Bangime is an endangered language classified as 6a - Vigorous by Ethnologue. Long known to be highly divergent from the (other) Dogon languages, it was first proposed as a possible isolate by Blench (2005). Heath and Hantgan have hypothesized that the cliffs surrounding the Bangande valley provided isolation of the language as well as safety for Bangande people. Even though Bangime is not closely related to Dogon languages, the Bangande still consider their language to be Dogon. Hantgan and List report that Bangime speakers seem unaware that it is not mutually intelligible with any Dogon language.

Baiso or Bayso is a Lowland East Cushitic language belonging to the Omo–Tana subgroup, and is spoken in Ethiopia, in the region around Lake Abaya.

Paamese, or Paama, is the language of the island of Paama in Northern Vanuatu. There is no indigenous term for the language; however linguists have adopted the term Paamese to refer to it. Both a grammar and a dictionary of Paamese have been produced by Terry Crowley.

Yolmo (Hyolmo) or Helambu Sherpa, is a Tibeto-Burman language of the Hyolmo people of Nepal. Yolmo is spoken predominantly in the Helambu and Melamchi valleys in northern Nuwakot District and northwestern Sindhupalchowk District. Dialects are also spoken by smaller populations in Lamjung District and Ilam District and also in Ramecchap District. It is very similar to Kyirong Tibetan and less similar to Standard Tibetan and Sherpa. There are approximately 10,000 Yolmo speakers, although some dialects have larger populations than others.

Pech or Pesh is a Chibchan language spoken in Honduras. It was formerly known as Paya, and continues to be referred to in this manner by several sources, though there are negative connotations associated with this term. It has also been referred to as Seco. There are 300 speakers according to Yasugi (2007). It is spoken near the north-central coast of Honduras, in the Dulce Nombre de Culmí municipality of Olancho Department.

Ramarama, also known as Karo, is a Tupian language of Brazil.

Daga is a non-Austronesian language of Papua New Guinea. Daga is spoken by about 9,000 people as of 2007. The peoples that speak Daga are located in the Rabaraba subdistrict of Milne Bay district, and in the Abau subdistrict of the Central district of Papua New Guinea.

Maia is a Papuan language spoken in the Madang Province of Papua New Guinea, and is a member of the Trans-New Guinea language family. It has a language endangerment status of 6a, which means that it is a vigorous and sustainable language spoken by all generations. According to a 2000 census, there are approximately 4,500 living speakers of the language, who are split between twenty-two villages in the Almani district of the Bogia sub-district.

Wandala, also known as Mandara or Mura', is a language in the Chadic branch of the Afro-Asiatic language family, spoken in Cameroon and Nigeria.

Mungbam is a Southern Bantoid language of the Lower Fungom region of Cameroon. It is traditionally classified as a Western Beboid language, but the language family is disputed. Good et al. uses a more accurate name, the 'Yemne-Kimbi group,' but proposes the term 'Beboid.'

Mekéns (Mekem), or Amniapé, is a nearly extinct Tupian language of the state of Rondônia, in the Amazon region of Brazil.

Avá-Canoeiro, known as Avá or Canoe, is a minor Tupi–Guaraní language of the state of Goiás, in Brazil. It can be further divided into two dialects: Tocantins Avá-Canoeiro and Araguaia Avá-Canoeiro. All speakers of the language are monolingual.

Tamashek or Tamasheq is a variety of Tuareg, a Berber macro-language widely spoken by nomadic tribes across North Africa in Algeria, Mali, Niger, and Burkina Faso. Tamasheq is one of the three main varieties of Tuareg, the others being Tamajaq and Tamahaq.

Neveʻei, also known as Vinmavis, is an Oceanic language of central Malekula, Vanuatu. There are around 500 primary speakers of Neveʻei and about 750 speakers in total.

Pendau, or Umalasa, is a Celebic language of Sulawesi in Indonesia spoken by the approximately 4000 Pendau people who live in Central Sulawesi. Classified as an endangered language, Pendau is primarily spoken inside of Pendau villages whereas Indonesian is used to speak with neighboring communities and is the language of children's education and outside officials. The highest concentration of speakers is in and around Kecamatan Balaesang. There are no known dialects within the Pendau region, although speakers from the mainland can identify whether a speaker is from the Balaesang peninsula through their 'rhythm' or intonation pattern. In recent years, some Pendau leaders have worked with local government to preserve their language alongside Indonesian.

Zoogocho Zapotec, or Diža'xon, is a Zapotec language of Oaxaca, Mexico.