History

Medieval & Early Modern Shanghai

Shanghai began as a fishing village at the confluence of the Wusong and Huangpu Rivers during the early medieval period. Under the Yuan, the Songjiang native Huang Daopo introduced new strains of cotton and improved techniques for working and dyeing it, improving the area's economic conditions just as the upper reaches of the Wusong River were thoroughly silting up, creating the modern Suzhou Creek and shifting commerce to the Huangpu. Under the Ming, Shanghai was raised in status from a town to a new county seat. A massive city wall was erected and the city's many canals were used to create a wide moat around it. [1]

Even after the city's promotion in status and the establishment of one of the country's few official international ports, however, it was allowed to develop fairly organically. Streets generally ran north to south and east to west, but the city's canals were far more important as means of transport. No effort was made to bring the town into compatibility with traditional Chinese urban planning as codified in the Rites of Zhou 's Kaogongji .

Colonial Shanghai

The United Kingdom took and plundered Shanghai in 1842 during the last phase of the First Opium War. Under the terms of the Treaty of Nanjing, the city was reopened to foreign trade as one of the first five treaty ports. An area of farmland around the city was yielded to foreign settlement in the form of a permanent lease. Consul Balfour laid out the initial plan of the British Concession along the west bank of the Huangpu from Yangjing Creek near the northern gate of the Chinese city to the south bank of Suzhou Creek. [2] The commercial establishments along the river bank were the beginning of the city's Bund. The French soon followed, taking the southern Bund, a strip of land between the British lease and the Chinese city, and a wider area northwest of the city.

Beginning in 1853, refugees from cities destroyed by the Taiping Rebellion and from the Chinese city after its conquest by the Small Sword Society quickly ballooned the population of the foreign territories from having no official Chinese residents to somewhere between 300,000 and 500,000. The territories expanded and developed, with the colonial administrators attempting to create a "model settlement" along the lines of 19th-century London and Paris with paved streets, a tram system, a pure and continuous water supply, and sewage treatment adequate to minimize outbreaks of cholera. [3] The British and French administrators had continual difficulty in coordinated planning but generally the British area around Nanjing Road developed into the city's dense commercial center while the French Concession was more open and residential. After the provision of an American concession, it merged with the British area as the Shanghai International Settlement while the French area remained separately administered.

Republican Shanghai

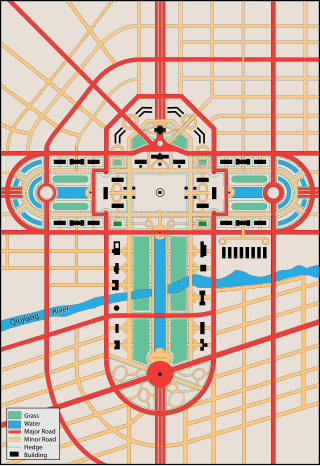

Having established a Greater Shanghai in 1927 that combined the administration of the old city (Nanshi) and the Chinese suburbs north of the international settlements (Zhabei), the Nationalist Government of the Republic of China in Nanjing formed an urban planning commission of both Chinese experts and foreign consultants. Their "Greater Shanghai Plan" ( t 民國 大 上海 計劃 , s 民国 大 上海 计划 ,Mínguó Dà Shànghǎi Jìhuà) published in July 1929 aimed to create greater autonomy for the Chinese by creating a new planned city at Jiangwan, shifting the Chinese government offices and center of population northeast between the international settlement and the expanding international port along the Yangtze River. The plan included rail and port expansions and a system of broad rectilinear streets to alleviate traffic congestion. The plan also designated around 15% of the area for parks and open spaces, with the most ambitious element being a civic center, occupying 333 acres (1,350,000 m2) and including a 50 m (160 ft) high pagoda and Washington-style reflecting pool. [4] The plan was rendered moot by the Japanese conquest and occupation of Shanghai between 1937 and 1945. The Japanese destroyed surviving public works created under the plan's guidance and eliminated the city's foreign enclaves. Upon their surrender, the Republic of China refused to restore the privileged foreign territories and the relocation of government offices and population was unneeded.

A second master plan was instead drafted by a city planning board established in 1946. This plan placed a great deal of emphasis on its relationship with broader regional planning. In particular, it proposed the development of Pudong on the east bank of the Huangpu and the establishment of bridge and tunnel connections between it and central Shanghai. [5] This plan was still in the process of enactment when the Nationalist defeat in the Chinese Civil War led to its annulment, the People's Liberation Army entering the city in 1949.

Maoist Shanghai

Following two decades of war, the first priority of the People's Republic of China with regards to Shanghai's urban planning was the restoration of all impaired utilities, communication, transportation, and other basic infrastructure. This was carried out from 1949 to 1956. From 1956, a massive urban renewal project was undertaken for Zhabei District. Further, forced relocation spread the population and industry through seven satellite towns within Shanghai Municipality but outside the urban core itself. [6] Hundreds of thousands of students or recent graduates also became sent-down youth, removed to Anhui or other provinces.

A series of political movements including the Great Leap Forward and the Cultural Revolution further impacted the city's economic development in the name of various social goals. This ended with the death of Mao Zedong, the fall of the Gang of Four that initially succeeded him, and the establishment of the Opening Up Policy under Deng Xiaoping in the late 1970s and early 1980s.

Modern Shanghai

Pudong New Area and several neighborhoods in Shanghai currently operate under special administration to facilitate business, particularly with regard to finance, high technology, exports, and entertainment. The city has also refurbished its religious and historical sites with an eye to promoting tourism. The current urban plan, however, aims to commit all levels of the city government to restricting the municipality's population to 25,000,000 permanent residents and 3,200 km2 (1,200 sq mi) of developed land. This is partially intended to improve provision of public services to city residents until nearly all basic needs can be addressed within a 15 minute radius and partially to encourage more widespread development in other areas of China.