| Yo Soy 132 | |

|---|---|

| Part of the 2012 Mexican general election, Impact of the Arab Spring | |

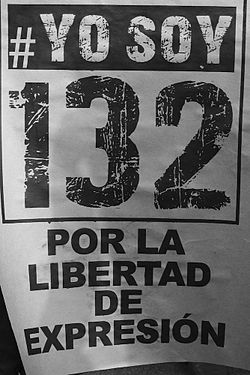

Poster stating #YoSoy132 against EPN: it's not hate nor intolerance against his name, but rather being full of indignation as to what he represents | |

| Date | 15 May 2012 –2013 [1] |

| Location | Mexico |

| Caused by | |

| Goals |

|

| Methods | |

| Resulted in |

|

| www www @Soy132mx @global132 | |

Yo Soy 132, commonly stylized as #YoSoy132, was a protest movement composed of Mexican university students from both private and public universities, residents of Mexico, claiming supporters from about 50 cities around the world. [2] It began as opposition to the Institutional Revolutionary Party (PRI) candidate Enrique Peña Nieto and the Mexican media's allegedly biased coverage of the 2012 general election. [3] The name Yo Soy 132, Spanish for "I Am 132", originated in an expression of solidarity with the original 131 protest's initiators. The phrase drew inspiration from the Occupy movement and the Spanish 15-M movement. [4] [5] [6] The protest movement was known worldwide as the "Mexican spring" [7] [8] (an allusion to the Arab Spring) after claims made by its first spokespersons, [9] and called the "Mexican occupy movement" in the international press. [10]