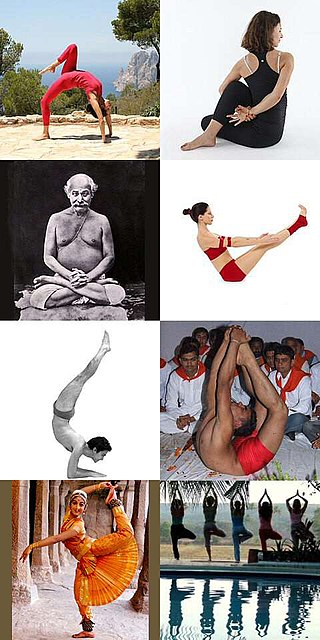

Yoga is a group of physical, mental, and spiritual practices or disciplines which originated in ancient India and aim to control (yoke) and still the mind, recognizing a detached witness-consciousness untouched by the mind (Chitta) and mundane suffering (Duḥkha). There is a wide variety of schools of yoga, practices, and goals in Hinduism, Buddhism, and Jainism, and traditional and modern yoga is practiced worldwide.

An āsana is a body posture, originally and still a general term for a sitting meditation pose, and later extended in hatha yoga and modern yoga as exercise, to any type of position, adding reclining, standing, inverted, twisting, and balancing poses. The Yoga Sutras of Patanjali define "asana" as "[a position that] is steady and comfortable". Patanjali mentions the ability to sit for extended periods as one of the eight limbs of his system. Asanas are also called yoga poses or yoga postures in English.

Pranayama is the yogic practice of focusing on breath. In yoga, breath is associated with prana, thus, pranayama is a means to elevate the prana-shakti, or life energies. Pranayama is described in Hindu texts such as the Bhagavad Gita and the Yoga Sutras of Patanjali. Later in Hatha yoga texts, it meant the complete suspension of breathing. The pranayama practices in modern yoga as exercise are unlike those of the Hatha yoga tradition.

The Complete Illustrated Book of Yoga is a bestselling 1960 book by Swami Vishnudevananda, the founder of the Sivananda Yoga Vedanta Centres. It is an introduction to Hatha yoga, describing the Yoga Sutras of Patanjali and the Hatha Yoga Pradipika. It contributed to the incorporation of Surya Namaskar into yoga as exercise. While some of its subject matter is the traditional philosophy of yoga, its detailed photographs of Vishnudevananda performing the asanas is modern, helping to market the Sivananda yoga brand to a global audience.

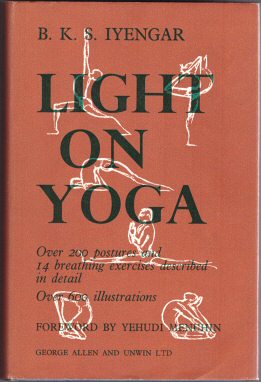

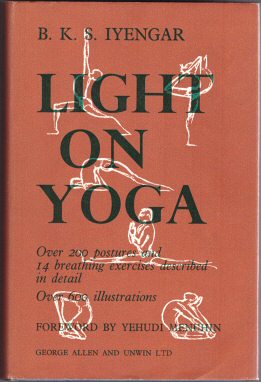

Light on Yoga: Yoga Dipika is a 1966 book on the Iyengar Yoga style of modern yoga as exercise by B. K. S. Iyengar, first published in English. It describes more than 200 yoga postures or asanas, and is illustrated with some 600 monochrome photographs of Iyengar demonstrating these.

Modern yoga is a wide range of yoga practices with differing purposes, encompassing in its various forms yoga philosophy derived from the Vedas, physical postures derived from Hatha yoga, devotional and tantra-based practices, and Hindu nation-building approaches.

Yoga as exercise is a physical activity consisting mainly of postures, often connected by flowing sequences, sometimes accompanied by breathing exercises, and frequently ending with relaxation lying down or meditation. Yoga in this form has become familiar across the world, especially in the US and Europe. It is derived from medieval Haṭha yoga, which made use of similar postures, but it is generally simply called "yoga". Academics have given yoga as exercise a variety of names, including modern postural yoga and transnational anglophone yoga.

Vajroli mudra, the Vajroli Seal, is a practice in Hatha yoga which requires the yogin to preserve his semen, either by learning not to release it, or if released by drawing it up through his urethra from the vagina of "a woman devoted to the practice of yoga".

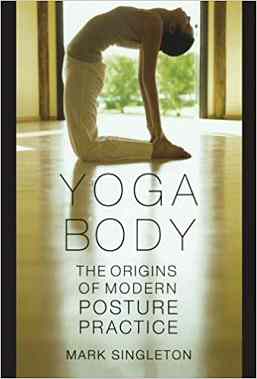

Mark Singleton is a scholar and practitioner of yoga. He studied yoga intensively in India, and became a qualified yoga teacher, until returning to England to study divinity and research the origins of modern postural yoga. His doctoral dissertation, which argued that posture-based forms of yoga represent a radical break from haṭha yoga tradition, with different goals, and an unprecedented emphasis on āsanas, was later published in book form as the widely-read Yoga Body.

Yoga Body: The Origins of Modern Posture Practice is a 2010 book on yoga as exercise by the yoga scholar Mark Singleton. It is based on his PhD thesis, and argues that the yoga known worldwide is, in large part, a radical break from hatha yoga tradition, with different goals, and an unprecedented emphasis on asanas, many of them acquired in the 20th century. By the 19th century, the book explains, asanas and their ascetic practitioners were despised, and the yoga that Vivekananda brought to the West in the 1890s was asana-free. Yet, from the 1920s, an asana-based yoga emerged, with an emphasis on its health benefits, and flowing sequences (vinyasas) adapted from the gymnastics of the physical culture movement. This was encouraged by Indian nationalism, with the desire to present an image of health and strength.

Selling Yoga : from Counterculture to Pop culture is a 2015 book on the modern practice of yoga as exercise by the scholar of religion, Andrea R. Jain.

The Path of Modern Yoga: The History of an Embodied Spiritual Practice is a 2016 history of the modern practice of postural yoga by the yoga scholar Elliott Goldberg. It focuses in detail on eleven pioneering figures of the transformation of yoga in the 20th century, including Yogendra, Kuvalayananda, Pant Pratinidhi, Krishnamacharya, B. K. S. Iyengar and Indra Devi.

Sexual abuse by yoga gurus is the exploitation of the position of trust occupied by a master of any branch of yoga for personal sexual pleasure. Allegations of such abuse have been made against modern yoga gurus such as Bikram Choudhury, Kausthub Desikachar, Yogi Bhajan, Amrit Desai, and K. Pattabhi Jois. There have been some criminal convictions and lawsuits for civil damages.

Early modern yoga was the form of yoga created and presented to the Western world by Madame Blavatsky, Swami Vivekananda and others in the late 19th century. It embodied the period's distaste for yoga postures (asanas) as practised by Nath yogins by not mentioning them. As such it differed markedly from the prevailing yoga as exercise developed in the 20th century by Yogendra, Kuvalayananda, and Krishnamacharya, which was predominantly physical, consisting mainly or entirely of asanas.

The history of yoga in the United States begins in the 19th century, with the philosophers Ralph Waldo Emerson and Henry David Thoreau; Emerson's poem "Brahma" states the Hindu philosophy behind yoga. More widespread interest in yoga can be dated to the Hindu leader Vivekananda's visit from India in 1893; he presented yoga as a spiritual path without postures (asanas), very different from modern yoga as exercise. Two other early figures, however, the women's rights advocate Ida C. Craddock and the businessman and occultist Pierre Bernard, created their own interpretations of yoga, based on tantra and oriented to physical pleasure.

Postural yoga began in India as a variant of traditional yoga, which was a mainly meditational practice; it has spread across the world and returned to the Indian subcontinent in different forms. The ancient Yoga Sutras of Patanjali mention yoga postures, asanas, only briefly, as meditation seats. Medieval Haṭha yoga made use of a small number of asanas alongside other techniques such as pranayama, shatkarmas, and mudras, but it was despised and almost extinct by the start of the 20th century. At that time, the revival of postural yoga was at first driven by Indian nationalism. Advocates such as Yogendra and Kuvalayananda made yoga acceptable in the 1920s, treating it as a medical subject. From the 1930s, the "father of modern yoga" Krishnamacharya developed a vigorous postural yoga, influenced by gymnastics, with transitions (vinyasas) that allowed one pose to flow into the next.

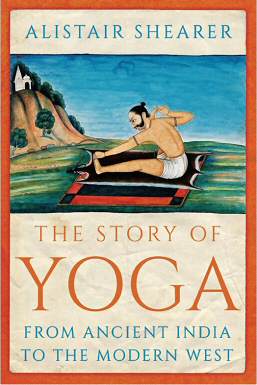

The Story of Yoga: From Ancient India to the Modern West is a cultural history of yoga by Alistair Shearer, published by Hurst in 2020. It narrates how an ancient spiritual practice in India became a global method of exercise, often with no spiritual content, by way of diverse movements including Indian nationalism, the Theosophical Society, Swami Vivekananda's coming to the west, self-publicising western yogis, Indian muscle builders, Krishnamacharya's practice in Mysore, and pioneering teachers like B. K. S. Iyengar.

Yoga in Britain: stretching spirituality and educating Yogis is a 2019 book by Suzanne Newcombe on the history of modern yoga as exercise in Britain in the second half of the 20th century, especially in the period between 1945 and 1980. The book has been warmly received by scholars for its depth of study of the history and sociology of yoga in Britain, and its careful placing of its descriptions in specific contexts of time and place.

Modern yoga gurus are people widely acknowledged to be gurus of modern yoga in any of its forms, whether religious or not. The role implies being well-known and having a large following; in contrast to the old guru-shishya tradition, the modern guru-follower relationship is not secretive, not exclusive, and does not necessarily involve a tradition. Many such gurus, but not all, teach a form of yoga as exercise; others teach forms which are more devotional or meditational; many teach a combination. Some have been affected by scandals of various kinds.

Yoga in advertising is the use of images of modern yoga as exercise to market products of any kind, whether related to yoga or not. Goods sold in this way have included canned beer, fast food and computers.