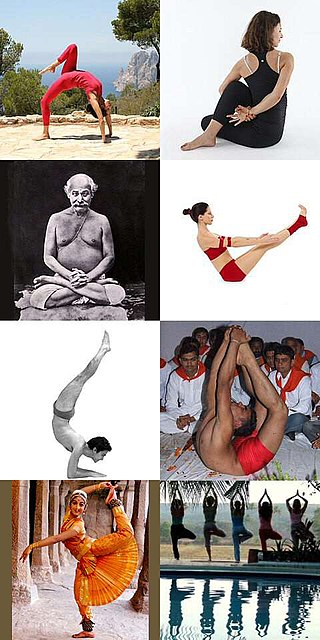

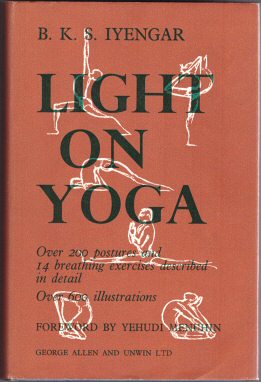

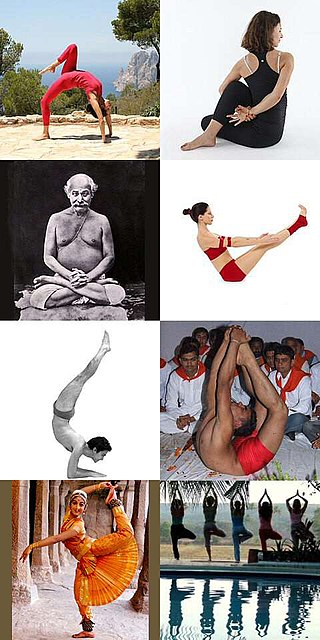

Iyengar Yoga, named after and developed by B. K. S. Iyengar, and described in his bestselling 1966 book Light on Yoga, is a form of yoga as exercise that has an emphasis on detail, precision and alignment in the performance of yoga postures (asanas).

Lotus position or Padmasana is a cross-legged sitting meditation pose from ancient India, in which each foot is placed on the opposite thigh. It is an ancient asana in yoga, predating hatha yoga, and is widely used for meditation in Hindu, Tantra, Jain, and Buddhist traditions.

An āsana is a body posture, originally and still a general term for a sitting meditation pose, and later extended in hatha yoga and modern yoga as exercise, to any type of position, adding reclining, standing, inverted, twisting, and balancing poses. The Yoga Sutras of Patanjali define "asana" as "[a position that] is steady and comfortable". Patanjali mentions the ability to sit for extended periods as one of the eight limbs of his system. Asanas are also called yoga poses or yoga postures in English.

Cosmetic advertising is the promotion of cosmetics and beauty products by the cosmetics industry through a variety of media. The advertising campaigns are usually aimed at women wishing to improve their appearance, commonly to increase physical attractiveness and reduce the signs of ageing.

Downward Dog Pose or Downward-facing Dog Pose, also called Adho Mukha Svanasana, is an inversion asana, often practised as part of a flowing sequence of poses, especially Surya Namaskar, the Salute to the Sun. The asana is commonly used in modern yoga as exercise. The asana does not have formally named variations, but several playful variants are used to assist beginning practitioners to become comfortable in the pose.

Lululemon athletica inc., commonly known as lululemon, is a Canadian-American multinational athletic apparel retailer headquartered in British Columbia and incorporated in Delaware, United States. It was founded in 1998 as a retailer of yoga pants and other yoga wear, and has expanded to also sell athletic wear, lifestyle apparel, accessories, and personal care products. The company has 574 stores internationally and sells online.

The Complete Illustrated Book of Yoga is a bestselling 1960 book by Swami Vishnudevananda, the founder of the Sivananda Yoga Vedanta Centres. It is an introduction to Hatha yoga, describing the Yoga Sutras of Patanjali and the Hatha Yoga Pradipika. It contributed to the incorporation of Surya Namaskar into yoga as exercise. While some of its subject matter is the traditional philosophy of yoga, its detailed photographs of Vishnudevananda performing the asanas is modern, helping to market the Sivananda yoga brand to a global audience.

John Friend, born Clifford Friend, is an American yoga guru and creator of Anusara Yoga.

Yoga pants are high-denier hosiery reaching from ankle to waist, originally designed for yoga as exercise and first sold in 1998 by Lululemon, a company founded for that purpose. They were initially made of a mix of nylon and Lycra; more specialised fabrics have been introduced to provide moisture-wicking, compression, and odour reduction.

Glow & Lovely is a skin-lightening cosmetic product of Hindustan Unilever introduced to the market in India in 1975. Glow & Lovely is available in India, Bangladesh, Malaysia, Indonesia, Singapore, Brunei, Thailand, Sri Lanka, Pakistan, Mauritius and other parts of Asia and is also exported to other parts of the world, such as the West, where it is sold in Asian supermarkets.

Tirumalai Krishnamacharya Venkata Desikachar, better known as T. K. V. Desikachar, was a yoga teacher, son of the pioneer of modern yoga as exercise, Tirumalai Krishnamacharya. The style that he taught was initially called Viniyoga although he later abandoned that name and asked for the methods he taught to be called "yoga" without special qualification.

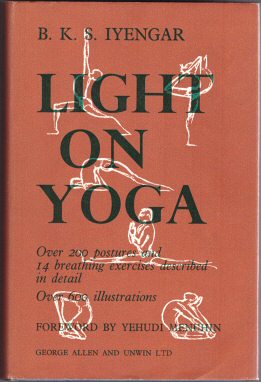

Light on Yoga: Yoga Dipika is a 1966 book on the Iyengar Yoga style of modern yoga as exercise by B. K. S. Iyengar, first published in English. It describes more than 200 yoga postures or asanas, and is illustrated with some 600 monochrome photographs of Iyengar demonstrating these.

Yoga as exercise is a physical activity consisting mainly of postures, often connected by flowing sequences, sometimes accompanied by breathing exercises, and frequently ending with relaxation lying down or meditation. Yoga in this form has become familiar across the world, especially in the US and Europe. It is derived from medieval Haṭha yoga, which made use of similar postures, but it is generally simply called "yoga". Academics have given yoga as exercise a variety of names, including modern postural yoga and transnational anglophone yoga.

Selling Yoga : from Counterculture to Pop culture is a 2015 book on the modern practice of yoga as exercise by the scholar of religion, Andrea R. Jain.

The Path of Modern Yoga: The History of an Embodied Spiritual Practice is a 2016 history of the modern practice of postural yoga by the yoga scholar Elliott Goldberg. It focuses in detail on eleven pioneering figures of the transformation of yoga in the 20th century, including Yogendra, Kuvalayananda, Pant Pratinidhi, Krishnamacharya, B. K. S. Iyengar and Indra Devi.

Modern yoga as exercise has often been taught by women to classes consisting mainly of women. This continued a tradition of gendered physical activity dating back to the early 20th century, with the Harmonic Gymnastics of Genevieve Stebbins in the US and Mary Bagot Stack in Britain. One of the pioneers of modern yoga, Indra Devi, a pupil of Krishnamacharya, popularised yoga among American women using her celebrity Hollywood clients as a lever.

A yoga brick or yoga block is a smooth block of wood or of firm but comfortable material, such as hard foam rubber or cork, used as a prop in yoga as exercise.

Postural yoga began in India as a variant of traditional yoga, which was a mainly meditational practice; it has spread across the world and returned to the Indian subcontinent in different forms. The ancient Yoga Sutras of Patanjali mention yoga postures, asanas, only briefly, as meditation seats. Medieval Haṭha yoga made use of a small number of asanas alongside other techniques such as pranayama, shatkarmas, and mudras, but it was despised and almost extinct by the start of the 20th century. At that time, the revival of postural yoga was at first driven by Indian nationalism. Advocates such as Yogendra and Kuvalayananda made yoga acceptable in the 1920s, treating it as a medical subject. From the 1930s, the "father of modern yoga" Krishnamacharya developed a vigorous postural yoga, influenced by gymnastics, with transitions (vinyasas) that allowed one pose to flow into the next.

Props used in yoga include chairs, blocks, belts, mats, blankets, bolsters, and straps. They are used in postural yoga to assist with correct alignment in an asana, for ease in mindful yoga practice, to enable poses to be held for longer periods in Yin Yoga, where support may allow muscles to relax, and to enable people with movement restricted for any reason, such as stiffness, injury, or arthritis, to continue with their practice.

Yoga is by origin an ancient spiritual practice from India. In the form of yoga as exercise, using postures (asanas) derived from medieval Haṭha yoga, it has become a widespread fitness practice across the western world. Yoga as exercise, along with the use that some make of symbols such as Om ॐ, has been described as cultural appropriation.