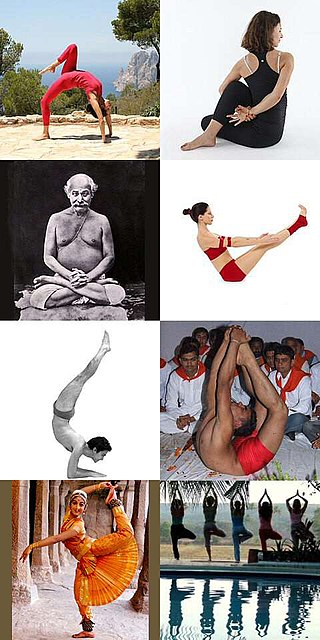

Yoga is a group of physical, mental, and spiritual practices or disciplines which originated in ancient India and aim to control (yoke) and still the mind, recognizing a detached witness-consciousness untouched by the mind (Chitta) and mundane suffering (Duḥkha). There is a wide variety of schools of yoga, practices, and goals in Hinduism, Buddhism, and Jainism, and traditional and modern yoga is practiced worldwide.

Nikolai Konstantinovich Rerikh, better known as Nicholas Roerich, was a Russian painter, writer, archaeologist, theosophist, philosopher, and public figure. In his youth he was influenced by Russian Symbolism, a movement in Russian society centered on the spiritual. He was interested in hypnosis and other spiritual practices and his paintings are said to have hypnotic expression.

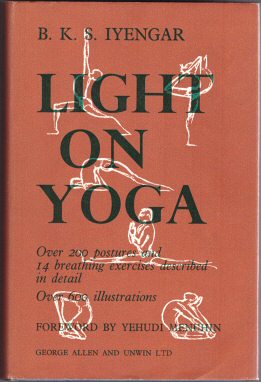

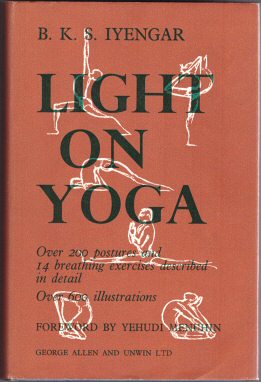

Bellur Krishnamachar Sundararaja Iyengar was an Indian teacher of yoga and author. He is the founder of the style of yoga as exercise, known as "Iyengar Yoga", and was considered one of the foremost yoga gurus in the world. He was the author of many books on yoga practice and philosophy including Light on Yoga, Light on Pranayama, Light on the Yoga Sutras of Patanjali, and Light on Life. Iyengar was one of the earliest students of Tirumalai Krishnamacharya, who is often referred to as "the father of modern yoga". He has been credited with popularizing yoga, first in India and then around the world.

An āsana is a body posture, originally and still a general term for a sitting meditation pose, and later extended in hatha yoga and modern yoga as exercise, to any type of position, adding reclining, standing, inverted, twisting, and balancing poses. The Yoga Sutras of Patanjali define "asana" as "[a position that] is steady and comfortable". Patanjali mentions the ability to sit for extended periods as one of the eight limbs of his system. Asanas are also called yoga poses or yoga postures in English.

The Yoga Sutras of Patañjali is a collection of Sanskrit sutras (aphorisms) on the theory and practice of yoga – 195 sutras and 196 sutras. The Yoga Sutras was compiled in the early centuries CE, by the sage Patanjali in India who synthesized and organized knowledge about yoga from much older traditions.

Pranayama is the yogic practice of focusing on breath. In yoga, breath is associated with prana, thus, pranayama is a means to elevate the prana-shakti, or life energies. Pranayama is described in Hindu texts such as the Bhagavad Gita and the Yoga Sutras of Patanjali. Later in Hatha yoga texts, it meant the complete suspension of breathing. The pranayama practices in modern yoga as exercise are unlike those of the Hatha yoga tradition.

Kriya Yoga is a yoga system which consists of a number of levels of pranayama, mantra, and mudra, intended to rapidly accelerate spiritual development and engender a profound state of tranquility and God-communion. It is described by its practitioners as an ancient yoga system revived in modern times by Lahiri Mahasaya, who claimed to be initiated by a guru, Mahavatar Babaji, circa 1861 in the Himalayas. Kriya Yoga was brought to international awareness by Paramahansa Yogananda's book Autobiography of a Yogi and through Yogananda's introductions of the practice to the West from 1920.

Prakriti is "the original or natural form or condition of anything, original or primary substance". It is a key concept in Hinduism, formulated by its Sāṅkhya school, where it does not refer to matter or nature, but "includes all the cognitive, moral, psychological, emotional, sensorial and physical aspects of reality", stressing "Prakṛti's cognitive, mental, psychological and sensorial activities". Prakriti has three different innate qualities (guṇas), whose equilibrium is the basis of all observed empirical reality as the five panchamahabhootas namely Akasha, Vayu, Agni, Jala, Pruthvi. Prakriti, in this school, contrasts with Puruṣa, which is pure awareness and metaphysical consciousness. The term is also found in the texts of other Indian religions such as Jainism and Buddhism.

Helena Ivanovna Roerich was a Russian theosophist, writer, and public figure. In the early 20th century, she created, in cooperation with the Teachers of the East, a philosophic teaching of Living Ethics. She was an organizer and participant of cultural activity in the U.S., conducted under the guidance of her husband, Nicholas Roerich. Along with her husband, she took part in expeditions of hard-to-reach and little-investigated regions of Central Asia. She was an Honorary President-Founder of the Institute of Himalayan Studies "Urusvati" in India and co-author of the idea of the International Treaty for Protection of Artistic and Scientific Institutions and Historical Monuments. She translated two volumes of the Secret Doctrine of H. P. Blavatsky, and selected Mahatma's Letters, from English to Russian.

Russian cosmism, also cosmism, is a later term for philosophical and cultural movement that emerged in Russia at the turn of the 19th century, and again, at the beginning of the 20th century. At the beginning of the 20th century, there was a burst of scientific investigation into interplanetary travel, largely driven by fiction writers such as Jules Verne and H. G. Wells as well as philosophical movements like the Russian cosmism.

Abhyāsa, in Hinduism, is a spiritual practice which is regularly and constantly practised over a long period of time. It has been prescribed by the great sage Patanjali in his Yoga Sutras, and by Krishna in the Bhagavad Gita as an essential means to control the mind, together with Vairāgya.

Kumbhaka is the retention of the breath in the yoga practice of pranayama. It has two types, accompanied whether after inhalation or after exhalation, and, the ultimate aim, unaccompanied. That state is kevala kumbhaka, the complete suspension of the breath for as long as the practitioner wishes.

George Nicolas de Roerich was a prominent 20th-century Tibetologist. His name at birth was YuriNikolaevich Rerikh. George's work encompassed many areas of Tibetan studies, but in particular he is known for his contributions to Tibetan dialectology, his monumental translation of the Blue Annals, and his 11-volume Tibetan-Russian-English dictionary.

Agni Yoga or the Living Ethics, or the Teaching of Life, is a Neo-Theosophical religious doctrine transmitted by Helena Roerich and Nicholas Roerich from 1920. The term Agni Yoga means "Mergence with Divine Fire" or "Path to Mergence with Divine Fire". This term was introduced by the Roerichs. The followers of Agni Yoga believe that the teaching was given to the Roerich family and their associates by Master Morya, the guru of the Roerichs and of Helena Blavatsky, one of the founders of the modern Theosophical movement and of the Theosophical Society.

Viktor Sergeyevich Boyko (Russian: Виктор Серге́евич Бойко; is a Russian yoga researcher and therapist. He uses the traditional Yoga Sutras of Patanjali within his own business, the Yoga School of Viktor Boyko, which was the first school of yoga in Russia and has branches across the country. He is the author of several books on yoga.

Roerichism or Rerikhism is a spiritual, cultural and social movement that emerged in the United States in the first half of the twentieth century, though it has been described as a "thoroughly Russian new religious movement", due to its close connection with Russia.

Victor Andreevich Skumin is a Russian and Soviet scientist, psychiatrist, philosopher and writer.

Light on Yoga: Yoga Dipika is a 1966 book on the Iyengar Yoga style of modern yoga as exercise by B. K. S. Iyengar, first published in English. It describes more than 200 yoga postures or asanas, and is illustrated with some 600 monochrome photographs of Iyengar demonstrating these.

Richard Rudzitis was a Latvian and Soviet poet, writer, translator and philosopher. He was chairman of the Latvian Roerich Cultural Relations Association from 1936 to 1940.

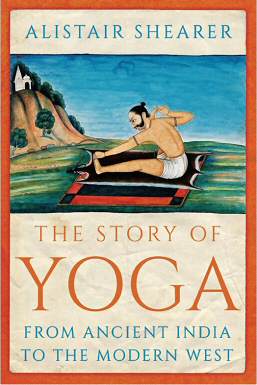

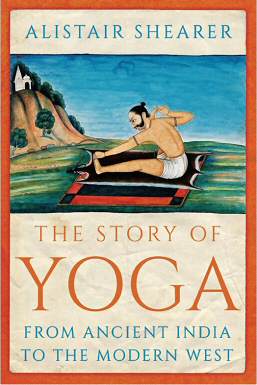

The Story of Yoga: From Ancient India to the Modern West is a cultural history of yoga by Alistair Shearer, published by Hurst in 2020. It narrates how an ancient spiritual practice in India became a global method of exercise, often with no spiritual content, by way of diverse movements including Indian nationalism, the Theosophical Society, Swami Vivekananda's coming to the west, self-publicising western yogis, Indian muscle builders, Krishnamacharya's practice in Mysore, and pioneering teachers like B. K. S. Iyengar.