K2, at 8,611 metres (28,251 ft) above sea level, is the second-highest mountain on Earth, after Mount Everest at 8,849 metres (29,032 ft). It lies in the Karakoram range, partially in the Gilgit-Baltistan region of Pakistan-administered Kashmir and partially in the China-administered Trans-Karakoram Tract in the Taxkorgan Tajik Autonomous County of Xinjiang.

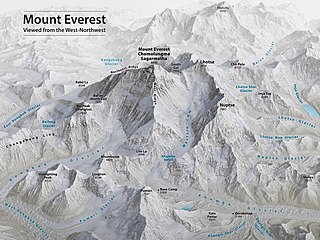

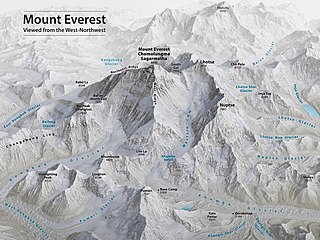

Mount Everest is Earth's highest mountain above sea level, located in the Mahalangur Himal sub-range of the Himalayas. The China–Nepal border runs across its summit point. Its elevation of 8,848.86 m was most recently established in 2020 by the Chinese and Nepali authorities.

Lhotse is the fourth highest mountain in the world at 8,516 metres (27,940 ft), after Mount Everest, K2, and Kangchenjunga. The main summit is on the border between Tibet Autonomous Region of China and the Khumbu region of Nepal.

Makalu is the fifth highest mountain in the world at 8,485 metres (27,838 ft). It is located in the Mahalangur Himalayas 19 km (12 mi) southeast of Mount Everest, on the China–Nepal border. One of the eight-thousanders, Makalu is an isolated peak in the shape of a four-sided pyramid.

Cho Oyu is the sixth-highest mountain in the world at 8,188 metres (26,864 ft) above sea level. Cho Oyu means "Turquoise Goddess" in Tibetan. The mountain is the westernmost major peak of the Khumbu sub-section of the Mahalangur Himalaya 20 km west of Mount Everest. The mountain stands on the China Tibet–Nepal Koshi Pradesh border.

Dhaulagiri, located in Nepal, is the seventh highest mountain in the world at 8,167 metres (26,795 ft) above sea level, and the highest mountain within the borders of a single country. It was first climbed on 13 May 1960 by a Swiss-Austrian-Nepali expedition. Annapurna I is 34 km (21 mi) east of Dhaulagiri. The Kali Gandaki River flows between the two in the Kaligandaki Gorge, said to be the world's deepest. The town of Pokhara is south of the Annapurnas, an important regional center and the gateway for climbers and trekkers visiting both ranges as well as a tourist destination in its own right.

Pumori is a mountain on the Nepal-China border in the Mahalangur section of the Himalayas. Pumori lies just eight kilometres west of Mount Everest. Pumori, meaning "the Mountain Daughter" in Sherpa language, was named by George Mallory. "Pumo" means young girl or daughter and "Ri" means mountain in Sherpa language. Climbers sometimes refer to Pumori as "Everest's Daughter". Mallory also called it Clare Peak, after his daughter.

Scott Eugene Fischer was an American mountaineer and mountain guide. He was renowned for his ascents of the world's highest mountains made without the use of supplemental oxygen. Fischer and Wally Berg were the first Americans to summit Lhotse, the world's fourth highest peak. Fischer, Charley Mace, and Ed Viesturs summitted K2 without supplemental oxygen. Fischer first climbed Mount Everest in 1994 and later died during the 1996 blizzard on Everest while descending from the peak.

Robert Edwin Hall was a New Zealand mountaineer. He was the head guide of a 1996 Mount Everest expedition during which he, a fellow guide, and two clients died. A best-selling account of the expedition was given in Jon Krakauer's Into Thin Air, and the expedition has been dramatised in the 2015 film Everest. At the time of his death, Hall had just completed his fifth ascent to the summit of Everest, more at that time than any other non-Sherpa mountaineer.

Mount Everest is the world's highest mountain, with a peak at 8,849 metres (29,031.7 ft) above sea level. It is situated in the Himalayan range of Solukhumbu district, Nepal.

Green Boots is the body of an unidentified climber that became a landmark on the main Northeast ridge route of Mount Everest. The body has not been officially identified, but is believed to be Tsewang Paljor, an Indian member of the Indo-Tibetan Border Police expedition (ITBP) who died as part of the 1996 climbing disaster on the mountain wearing green Koflach mountaineering boots. All expeditions from the north side encountered the body curled in the limestone alcove cave at 8,500 m (27,900 ft), until it was moved by the Chinese in 2014.

The 1996 Mount Everest disaster occurred on 10–11 May 1996 when eight climbers caught in a blizzard died on Mount Everest while attempting to descend from the summit. Over the entire season, 12 people died trying to reach the summit, making it the deadliest season on Mount Everest at the time and the third deadliest after the 22 fatalities resulting from avalanches caused by the April 2015 Nepal earthquake and the 16 fatalities of the 2014 Mount Everest avalanche. The 1996 disaster received widespread publicity and raised questions about the commercialization of Everest.

Lopsang Jangbu Sherpa was a Nepalese Sherpa mountaineering guide, climber and porter, best known for his work as the climbing Sirdar for Scott Fischer's Mountain Madness expedition to Everest in Spring 1996, when a freak storm led to the deaths of eight climbers from several expeditions, considered one of the worst disasters in the history of Everest mountaineering. Notwithstanding controversy over his actions during that expedition, Lopsang was well-regarded in the mountaineering community, having summited Everest four times. Lopsang was killed in an avalanche in September 1996, while again on an expedition to climb Everest for what would have been a fifth ascent.

The Three Steps are three prominent rocky steps on the northeast ridge of Mount Everest. They are located at altitudes of 8,564 metres (28,097 ft), 8,610 metres (28,250 ft), and 8,710 metres (28,580 ft). The Second Step is especially significant both historically and in mountaineering terms. Any climber who wants to climb on the normal route from the north of the summit must negotiate these three stages.

Ang Dorje (Chhuldim) Sherpa is a Nepalese sherpa mountaineering guide, climber, and porter from Pangboche, Nepal, who has climbed to the summit of Mount Everest 22 times. He was the climbing Sirdar for Rob Hall's Adventure Consultants expedition to Everest in spring 1996, when a freak storm led to the deaths of eight climbers from several expeditions, considered one of the worst disasters in the history of Everest mountaineering.

The 1975 British Mount Everest Southwest Face expedition was the first to successfully climb Mount Everest by ascending one of its faces. In the post-monsoon season Chris Bonington led the expedition that used rock climbing techniques to put fixed ropes up the face from the Western Cwm to just below the South Summit. A key aspect of the success of the climb was the scaling of the cliffs of the Rock Band at about 8,200 metres (27,000 ft) by Nick Estcourt and Tut Braithwaite.

The 1965 Indian Everest Expedition reached the summit of Mount Everest on 20 May 1965. It was the first successful scaling of the mountain by an Indian climbing expedition.