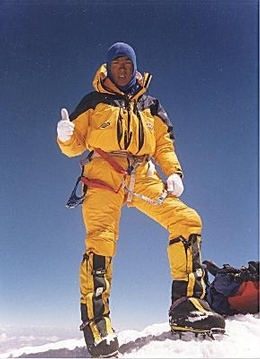

Tsewang Paljor

Eight climbers died in the Everest disaster of 1996: five climbers from the Adventure Consultants and Mountain Madness expeditions on the southeast route, and three fatalities among the Indo-Tibetan Border Police (ITBP) expedition from India who perished were on the northeast route. [7]

Green Boots is commonly believed to be Indian ITBP climber, Tsewang Paljor, [8] who was wearing green Koflach boots on the day he and two others in his party attempted to summit. However, the body may have been that of his team member Dorje Morup. The ITBP was led by Commandant Mohinder Singh and was the first Indian ascent of Everest from the east side. [9]

On 10 May 1996, Subedar Tsewang Smanla, Lance Naik Dorje Morup, and Head Constable Tsewang Paljor were caught in a blizzard just short of the summit. While three of the six-member team turned back down, Smanla, Morup, and Paljor decided to go for the summit. [10] At around 15:45 Nepal Time, the three climbers radioed to their expedition leader that they had arrived at the top. They left an offering of prayer flags, khatas, and pitons. Here, the leader, Smanla, decided to spend extra time on religious ceremonies and instructed the other two to move down.

There was no radio contact after that. Back at the camps below, team members saw two headlamps moving slightly above the Second Step, at 8,570 metres (28,117 ft). None of the three returned to high camp at 8,300 metres (27,231 ft).

Controversy later arose over whether or not a team of Japanese climbers from Fukuoka had seen and potentially failed to assist the missing Indian climbers. The group had left their camp at 8,300 metres (27,231 ft) at 06:15 Beijing time, reaching the summit at 15:07. Along the way, they encountered others on the trail. Unaware of the missing Indians, they believed these others, all wearing goggles and oxygen masks under their hoods, were members of a climbing party from Taiwan. During their descent, which began at 15:30, they reported seeing an unidentifiable object above the Second Step. Below the First Step, they radioed in to report seeing one person on a fixed rope. Thereafter, one of the climbers, Shigekawa, exchanged greetings with an unidentifiable man standing nearby. At that time, they had only enough oxygen to return to C6.

At 16:00, the Fukuoka party discovered from an Indian in their group that three men were missing. [11] They offered to join the rescue but were declined. Forced to wait a day due to bad weather, they sent a second party to the summit on 13 May. They saw several bodies around the First Step but continued to the summit.

Initially, there were some misunderstandings and harsh words regarding the actions of the Fukuoka team, which were later clarified. According to Reuters, the Indian expedition had claimed that the Japanese had pledged to help with the search but had pressed forward with their summit attempt. [12] The Japanese team denied that they had abandoned or refused to help the dying climbers on the way up, a claim that the Indian-Tibetan Border Police accepted. [11] Captain Kohli, an official of the Indian Mountaineering Federation, who earlier had denounced the Japanese, later retracted his claim that the Japanese had reported meeting the Indians on 10 May.

Dorje Morup

While it is commonly believed that Green Boots is the body of Head Constable Tsewang Paljor, a 1997 article titled "The Indian Ascent of Qomolungma by the North Ridge", published by the deputy leader of the expedition in Himalayan Journal P. M. Das, raises the possibility that it could instead be that of Lance Naik Dorje Morup, aka Dorje. Das wrote that two climbers had been spotted descending by the light of their head-torches at 19:30, although they were soon lost from sight. [13] The next day the leader of the second summit group of the expedition radioed base camp that they had encountered Morup moving slowly between the First and Second Steps. Das wrote that Morup "had refused to put on gloves over his frost-bitten hands" and "was finding difficulty in unclipping his safety carabiner at anchor points." [13] According to Das, the Japanese team assisted in transitioning him to the next stretch of rope.

Sometime later, the Japanese group discovered the body of Tsewang Smanla above the Second Step. On the return trip, the group found that Morup was progressing slowly. Morup is believed to have died in the late afternoon of 11 May. Das states that Paljor's body was never found.

A second ITBP group also came across the bodies of Smanla and Morup on their return from the summit. Das wrote that they encountered Morup "lying under the shelter of a boulder near their line of descent, close to Camp 6" with intact clothing and his rucksack by his side. [13]