Malvern is a borough in Chester County, Pennsylvania, United States. Malvern is the terminus of the Main Line, a series of highly affluent Philadelphia suburbs located along the railroad tracks of the Pennsylvania Railroad. It is 19.4 miles (31.2 km) west of Philadelphia. The population was 3,419 at the 2020 census.

Paoli is a census-designated place (CDP) in Chester County near Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, United States. It is situated in portions of two townships: Tredyffrin and Willistown. At the 2020 census, it had a total population of 6,002.

The Battle of Brandywine, also known as the Battle of Brandywine Creek, was fought between the American Continental Army of General George Washington and the British Army of General Sir William Howe on September 11, 1777, as part of the American Revolutionary War (1775–1783). The forces met near Chadds Ford, Pennsylvania. More troops fought at Brandywine than at any other battle of the American Revolution. It was also the second longest single-day battle of the war, after the Battle of Monmouth, with continuous fighting for 11 hours.

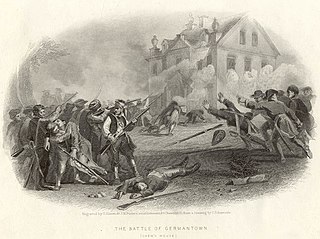

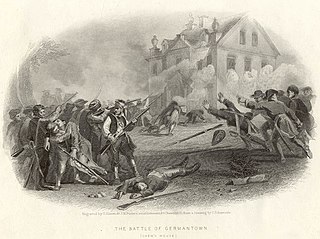

The Battle of Germantown was a major engagement in the Philadelphia campaign of the American Revolutionary War. It was fought on October 4, 1777, at Germantown, Pennsylvania, between the British Army led by Sir William Howe, and the American Continental Army under George Washington.

The Battle of Bound Brook was a surprise attack conducted by British and Hessian forces against a Continental Army outpost at Bound Brook, New Jersey during the American Revolutionary War. The British objective of capturing the entire garrison was not met, although prisoners were taken. The U.S. commander, Major General Benjamin Lincoln, left in great haste, abandoning papers and personal effects.

The 1st Pennsylvania Regiment - originally mustered as the 1st Pennsylvania Rifles; also known as the 1st Continental Line and 1st Continental Regiment, was raised under the command of Colonel William Thompson for service in the Continental Army.

The 6th Pennsylvania Regiment, first known as the 5th Pennsylvania Battalion, was a unit of the United States of America (U.S.) Army, raised December 9, 1775, at Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, for service with the Continental Army. The regiment would see action during the New York Campaign, Battle of Brandywine, Battle of Germantown, Battle of Monmouth, and Green Spring. The regiment was disbanded on January 1, 1783.

The 8th Pennsylvania Regiment or Mackay's Battalion was an American infantry unit that became part of the Continental Army during the American Revolutionary War. Authorized for frontier defense in July 1776, the eight-company unit was originally called Mackay's Battalion after its commander, Colonel Aeneas Mackay. Transferred to the main army in November 1776, the unit was renamed the 8th Pennsylvania Regiment on 1 January 1777. It completed an epic winter march from western Pennsylvania to New Jersey, though Mackay and his second-in-command both died soon afterward. In March 1777 Colonel Daniel Brodhead assumed command. The regiment was engaged at the Battles of Bound Brook, Brandywine, Paoli, and Germantown in 1777. A body of riflemen were detached from the regiment and fought at Saratoga. Assigned to the Western Department in May 1778, the 8th Pennsylvania gained a ninth company before seeing action near Fort Laurens and in the Sullivan Expedition in 1778 and 1779. The regiment consolidated with the 2nd Pennsylvania Regiment in January 1781 and ceased to exist.

The 11th Pennsylvania Regiment or Old Eleventh was authorized on 16 September 1776 for service with the Continental Army. On 25 October, Richard Humpton was named colonel. In December 1776, the regiment was assigned to George Washington's main army and was present at Assunpink Creek and fought at Princeton in January 1777. During the spring, the unit assembled at Philadelphia, Pennsylvania in a strength of eight companies. The soldiers were recruited from Philadelphia and four nearby counties. On 22 May 1777, the regiment became part of the 2nd Pennsylvania Brigade. The 11th was in the thick of the action at Brandywine, Paoli, and Germantown in 1777. It was present at White Marsh and Monmouth. On 1 July 1778, the unit was consolidated with the 10th Pennsylvania Regiment, and the 11th Regiment ceased to exist. Humpton took command of the reorganized unit.

The 9th Virginia Regiment was authorized in the Virginia State Troops on January 11, 1776. It was subsequently organized between February 5 and March 16, 1776, and comprised seven companies of troops from easternmost Virginia. The unit was adopted into the Continental Army on May 31, 1776. The regiment participated in the Battle of Brandywine and the Battle of Germantown. At Germantown, under the command of Colonel George Mathews, the unit penetrated so deeply into the British lines that it was isolated from the remainder of General Nathanael Greene's division and over 400 men were taken prisoner by the British. Four retreating companies of the 1st British Light Infantry Battalion found themselves in the rear of the Virginians and attacked. Surprised, the 9th was driven farther into the British camp where it was beset by the brigade of Charles Grey, 1st Earl Grey and the 2nd British Light Infantry Battalion. After being attacked on all sides and Mathews wounded, the regiment surrendered near Kelly's Hill together with part of the 6th Virginia Regiment. The unit was consolidated with the 1st Virginia Regiment on May 12, 1779, and the consolidated unit was designated as the 1st Virginia Regiment. The unit was captured on May 12, 1780, by the British Army at the Siege of Charleston and was disbanded on November 15, 1783.

Pennsylvania was the site of many key events associated with the American Revolution and American Revolutionary War. The city of Philadelphia, then capital of the Thirteen Colonies and the largest city in the colonies, was a gathering place for the Founding Fathers who discussed, debated, developed, and ultimately implemented many of the acts, including signing the Declaration of Independence, that inspired and launched the revolution and the quest for independence from the British Empire.

The Battle of White Marsh or Battle of Edge Hill was a battle of the Philadelphia campaign of the American Revolutionary War fought December 5–8, 1777, in the area surrounding Whitemarsh Township, Pennsylvania. The battle, which took the form of a series of skirmish actions, was the last major engagement of 1777 between British and American forces.

The Battle of Matson's Ford was a battle in the Philadelphia campaign of the American Revolutionary War fought on December 11, 1777 in the area surrounding Matson's Ford. In this series of minor skirmish actions, advance patrols of Pennsylvania militia encountered a British foraging expedition and were overrun. The British pushed ahead to Matson's Ford, where units of the Continental Army were making their way across the Schuylkill River. The Americans retreated to the far side, destroying their temporary bridge across the Schuylkill. The British left the area the next day to continue foraging elsewhere; the Continentals crossed the river at Swede's Ford to Bridgeport, Pennsylvania, a few miles upriver from Matson's Ford.

The Brandywine Battlefield Historic Site is a National Historical Landmark. The historic park is owned and operated by the Pennsylvania Historical and Museum Commission, on 52 acres (210,000 m2), near Chadds Ford, Delaware County, Pennsylvania in the United States.

The Battle of the Clouds was a failed attempt to delay the British advance on Philadelphia during the American Revolutionary War on September 16, 1777, in the area surrounding present day Malvern, Pennsylvania. After the American defeat at the Battle of Brandywine, the British Army remained encamped near Chadds Ford. When British commander William Howe was informed that the weakened American force was less than ten miles (16 km) away, he decided to press for another decisive victory.

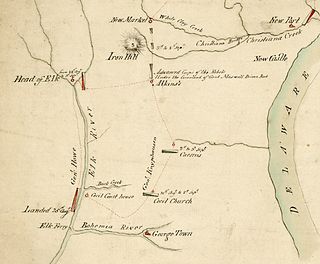

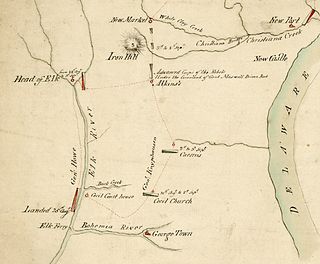

The Battle of Cooch's Bridge, also known as the Battle of Iron Hill, was fought on September 3, 1777, between the Continental Army and American militia and primarily German soldiers serving alongside the British Army during the American Revolutionary War. It was the only significant military action during the war on the soil of Delaware, and it took place about a week before the major Battle of Brandywine. Some traditions claim this as the first battle which saw the U.S. flag.

The following units and commanders fought in the Battle of Paoli during the American Revolutionary War. The Battle of Paoli was part of the Philadelphia campaign of the American Revolutionary War fought on September 21, 1777, in the area surrounding present-day Malvern, Pennsylvania.

At the Battle of Brandywine on September 11, 1777 a colonial American army led by General George Washington fought a British-Hessian army commanded by General William Howe, 5th Viscount Howe. Washington drew up his troops in a defensive position behind Brandywine Creek. Howe sent Lieutenant General Wilhelm von Knyphausen's 5,000 troops to demonstrate against the American front at Chadd's Ford. Meanwhile, Lieutenant General Charles Cornwallis took 10,000 troops on a wide flank march that crossed the creek and got in the rear of the American right wing under Major General John Sullivan. The Americans changed front but Howe's attack broke through.

Walter Stewart was an Irish-born American general in the Continental Army during the American Revolutionary War.

Hartley's Additional Continental Regiment was an American infantry unit of the Continental Army that served for two years during the American Revolutionary War. The regiment was authorized in January 1777 and Thomas Hartley was appointed its commander. The unit comprised eight companies from Pennsylvania, Maryland, and Delaware. When permanent brigades were formed in May 1777, the regiment was transferred to the 1st Pennsylvania Brigade. Hartley's Regiment fought at Brandywine, Paoli, and Germantown in 1777. The unit helped defend the Pennsylvania frontier against indigenous raids in the Summer and early Fall of 1778. In January 1779, following a resolution of the Continental Congress the regiment, along with Patton's Additional Continental Regiment and part of Malcolm's Additional Continental Regiment, were combined to form a complete battalion known as the "New" 11th Pennsylvania Regiment. The 11th participated in the Sullivan Expedition in the summer of that year. In January 1781 the 11th merged with the 3rd Pennsylvania Regiment and ceased to exist.