The demographics of Malaysia are represented by the multiple ethnic groups that exist in the country. Malaysia's population, according to the 2010 census, is 28,334,000 including non-citizens, which makes it the 42nd most populated country in the world. Of these, 5.72 million live in East Malaysia and 22.5 million live in Peninsular Malaysia. The population distribution is uneven, with some 79% of its citizens concentrated in Peninsular Malaysia, which has an area of 131,598 square kilometres (50,810.27 sq mi), constituting under 40% of the total area of Malaysia.

Perlis, also known by its honorific title Perlis Indera Kayangan, is a state of Malaysia in the northwestern coast of Peninsular Malaysia. It is the smallest state in Malaysia by means of area and population, as well as the northernmost in the country. The state borders the Thai provinces of Satun and Songkhla to the north and the Malaysian state of Kedah to the south. Perlis is the only Malaysian state that is not divided into any districts, due to its small size, but it is still divided into several communes. It was called Palit by the Siamese when it was under their influence. Perlis had a population of 227,025 as of the 2010 census.

While freedom of religion is de jure symbolically enshrined in the Malaysian Constitution, it de facto faces many prohibitions and restrictions. A Malay in Malaysia must strictly be a Muslim, and they cannot convert to another religion. Islamic religious practices are determined by official Sharia law, and Muslims can be fined by the state for not fasting or refusing to pray. The country does not consider itself a secular state and that Islam is the state religion of the country, and individuals with no religious affiliation are viewed with hostility.

Kedah, also known by its honorific Darul Aman and historically as Queda, is a state of Malaysia, located in the northwestern part of Peninsular Malaysia. The state covers a total area of over 9,000 km2, and it consists of the mainland and the Langkawi islands. The mainland has a relatively flat terrain, which is used to grow rice, while Langkawi is an archipelago, most of which are uninhabited islands.

Islam in Malaysia is represented by the Shafi‘i school of Sunni jurisprudence. Islam was introduced to Malaysia by traders arriving from Persia, Arabia, China and the Indian subcontinent. It became firmly established in the 15th century. In the Constitution of Malaysia, Islam is granted the status of "religion of the Federation" to symbolize its importance to Malaysian society, while defining Malaysia constitutionally as a secular state. Therefore, other religions can be practiced legally, though freedom of religion is still limited in Malaysia.

Christianity is a minority religion in Malaysia. In the 2020 census, 9.1% of the Malaysian population identified themselves as Christians. About two-thirds of Malaysia's Christian population lives in East Malaysia, in the states of Sabah and Sarawak. Adherents of Christianity represent a majority (50.1%) of the population in Sarawak, which is Malaysia's largest state by land area. Christianity is one of four major religions including Islam, Hinduism, and Buddhism that has a freedom protected by the law in Malaysia based of diversity law especially in East Malaysia.

Alor Setar is the state capital of Kedah, Malaysia. It is the second-largest city in the state after Sungai Petani and one of the most-important cities on the west coast of Peninsular Malaysia. It is home to the third-tallest telecommunication tower in Malaysia, the Alor Setar Tower.

Hinduism is the fourth-largest religion in Malaysia. About 1.78 million Malaysian residents are Hindus, according to 2010 Census of Malaysia. This is up from 1,380,400 in 2000.

The World Buddhist Sangha Council (WBSC) is an international non-government organisation (NGO) whose objectives are to develop the exchanges of the Buddhist religious and monastic communities of the different traditions worldwide, and help to carry out activities for the transmission of Buddhism. It was founded in Colombo, Sri Lanka in May 1966. Since 1981, Ven. Pai Sheng was elected as president of WBSC and the headquarter of WBSC had moved to Taipei, Taiwan.

Buddhist Maha Vihara is a Sri Lankan temple situated in Brickfields of Kuala Lumpur in Malaysia. The temple became a focal point for the annual Wesak festival within the city suburb.

Bukit Rimau is a township in Shah Alam, Klang District, Selangor, Malaysia.

The Malaysian Siamese are an ethnicity or community who principally resides in Peninsular Malaysia which is a relatively homogeneous cultural region to Southern Burma and Southern Thailand but was separated by the Anglo-Siamese Treaty of 1909 between the United Kingdom and the Kingdom of Siam. The treaty established the modern Malaysia-Thailand Border which starts from Golok River in Kelantan and ends at Padang Besar in Perlis.

Islam is the state religion of Malaysia, as per Article 3 of the Constitution. Meanwhile, other religions can be practised by non-Malay citizens of the country. In addition, per Article 160, one must be Muslim to be considered Malay. As of the 2020 Population and Housing Census, 63.5 percent of the population practices Islam; 18.7 percent Buddhism; 9.1 percent Christianity; 6.1 percent Hinduism; and 2.7 percent other religion or gave no information. The remainder is accounted for by other faiths, including Animism, Folk religion, Sikhism, Baháʼí Faith and other belief systems. The states of Sarawak and Penang and the federal territory of Kuala Lumpur have non-Muslim majorities. Numbers of self-described atheists in Malaysia are few as renouncing Islam is prohibited for Muslims in Malaysia. As such, the actual number of atheists or converts in the country is hard to ascertain out of fear from being ostracised or prosecution. The state has come under criticism from human rights organisations for the government's discrimination against atheists, with some cabinet members saying that "the freedom of religion is not the freedom from religion".

The Malaysian Consultative Council of Buddhism, Christianity, Hinduism, Sikhism and Taoism is a non-profit interfaith organization in Malaysia. Initially formed in 1983 as the "Malaysian Consultative Council of Buddhism, Christianity, Hinduism and Sikhism", it is composed primarily of officials from the main non-Muslim faith communities in Malaysia and acts as a consultative and liaison body towards more open dialogue and co-operation. It prioritizes round-table dialogue as its principal means towards conflict resolution amongst all Malaysians, irrespective of creed, religion, race, culture, or gender. In 2006, Taoists were officially represented for the first time in the organization and the name was changed to the current form in their Annual General Meeting on 27 September of the same year. Their current vision is represented through the slogan "Many Faiths, One Nation."

Taman Melati is a Malay majority township in Wangsa Maju, Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia. It is located between Gombak, Klang Gates, Wangsa Maju city centre and Taman Melawati. The 5 Kelana Jaya Line's KJ2 Taman Melati LRT station is situated in this area.

Sri Lankan Malaysians are people of full or partial Sri Lankan descent who were born in or immigrated to Malaysia.

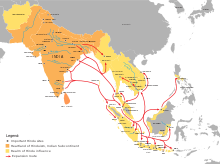

Southeast Asia was in the Indian sphere of cultural influence from 290 BCE to the 15th century CE, when Hindu-Buddhist influences were incorporated into local political systems. Kingdoms in the southeast coast of the Indian subcontinent had established trade, cultural and political relations with Southeast Asian kingdoms in Burma, Bhutan, Thailand, the Sunda Islands, Malay Peninsula, Philippines, Cambodia, Laos, and Champa. This led to the Indianisation and Sanskritisation of Southeast Asia within the Indosphere, Southeast Asian polities were the Indianised Hindu-Buddhist Mandala.

The Most Venerable Datuk K. Sri Dhammaratana 拿督达摩拉达那长老 is a Sri Lankan born Malaysian Buddhist monk and the incumbent Buddhist Chief High Priest of Malaysia, since the passing of his predecessor in 2006.