Ronald Wilson Reagan was an American politician and actor who served as the 40th president of the United States from 1981 to 1989. A member of the Republican Party, his presidency constituted the Reagan era, and he is considered one of the most prominent conservative figures in American history.

The Eighteenth Amendment to the United States Constitution established the prohibition of alcohol in the United States. The amendment was proposed by Congress on December 18, 1917, and ratified by the requisite number of states on January 16, 1919. The Eighteenth Amendment was repealed by the Twenty-first Amendment on December 5, 1933, making it the only constitutional amendment in American history to be repealed.

A veto is a legal power to unilaterally stop an official action. In the most typical case, a president or monarch vetoes a bill to stop it from becoming law. In many countries, veto powers are established in the country's constitution. Veto powers are also found at other levels of government, such as in state, provincial or local government, and in international bodies.

Richard Green Lugar was an American politician who served as a United States Senator from Indiana from 1977 to 2013. He was a member of the Republican Party.

Nancy Josephine Kassebaum Baker is an American politician from Kansas who served as a member of the United States Senate from 1978 to 1997. She is the daughter of Alf Landon, who was Governor of Kansas from 1933 to 1937 and the 1936 Republican nominee for president, and the widow of former U.S. senator and diplomat Howard Baker.

William Victor Roth Jr. was an American lawyer and politician from Wilmington, Delaware. He was a veteran of World War II and a member of the Republican Party. He served from 1967 to 1970 as the lone U.S. Representative from Delaware and from 1971 to 2001 as a U.S. Senator from Delaware. He is the last Republican to serve as and/or be elected a U.S. Senator from Delaware.

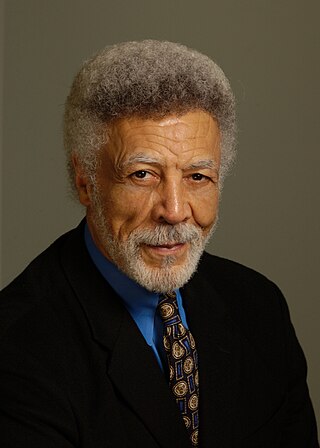

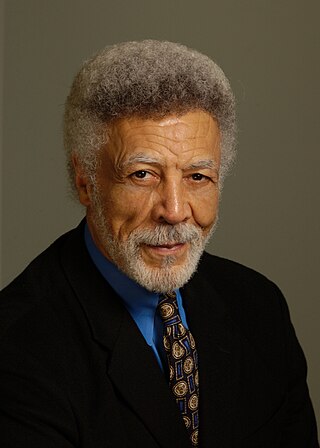

Ronald Vernie Dellums was an American politician who served as Mayor of Oakland from 2007 to 2011. He had previously served thirteen terms as a Member of the U.S. House of Representatives from California's 9th congressional district, in office from 1971 to 1998, after which he worked as a lobbyist in Washington, D.C.

Ronald Reagan's tenure as the 40th president of the United States began with his first inauguration on January 20, 1981, and ended on January 20, 1989. Reagan, a Republican from California, took office following his landslide victory over Democrat incumbent president Jimmy Carter and independent congressman John B. Anderson in the 1980 presidential election. Four years later, in the 1984 presidential election, he defeated former Democratic vice president Walter Mondale, to win re-election in a larger landslide. Reagan was succeeded by his vice president, George H. W. Bush, who won the 1988 presidential election. Reagan's 1980 landslide election resulted from a dramatic conservative shift to the right in American politics, including a loss of confidence in liberal, New Deal, and Great Society programs and priorities that had dominated the national agenda since the 1930s.

Robert Walter "Bob" Kasten Jr. is an American Republican politician from the state of Wisconsin who served as a U.S. Representative from 1975 to 1979 and as a United States Senator from 1981 to 1993.

The Civil Rights Restoration Act of 1987, or Grove City Bill, is a United States legislative act that specifies that entities receiving federal funds must comply with civil rights legislation in all of their operations, not just in the program or activity that received the funding. The Act overturned the precedent set by the Supreme Court decision in Grove City College v. Bell, 465 U.S. 555 (1984), which held that only the particular program in an educational institution receiving federal financial assistance was required to comply with the anti-discrimination provisions of Title IX of the Education Amendments of 1972, not the institution as a whole.

Earl Dewitt Hutto was an American politician who served as U.S. Representative from Florida's 1st congressional district.

Disinvestmentfrom South Africa was first advocated in the 1960s in protest against South Africa's system of apartheid, but was not implemented on a significant scale until the mid-1980s. A disinvestment policy the U.S. adopted in 1986 in response to the disinvestment campaign is credited with playing a role in pressuring the South African government to embark on negotiations that ultimately led to the dismantling of the apartheid system.

Constructive engagement was the name given to the conciliatory foreign policy of the Reagan administration towards the apartheid regime in South Africa. Devised by Chester Crocker, Reagan's U.S. Assistant Secretary of State for African Affairs, the policy was promoted as an alternative to the economic sanctions and divestment from South Africa demanded by the UN General Assembly and the international anti-apartheid movement. Among other objectives, it sought to advance regional peace in Southern Africa by linking the end of South Africa's occupation of Namibia to the end of the Cuban presence in Angola.

The United States and South Africa currently maintain bilateral relations with one another. The United States and South Africa have been economically linked to one another since the late 18th century which has continued into the 21st century. United States and South Africa relations faced periods of strain throughout the 20th century due to the segregationist, white minority rule in South Africa, from 1948 to 1994. Following the end of apartheid in South Africa, the United States and South Africa have developed a strategically, politically, and economically beneficial relationship with one another and currently enjoy "cordial relations" despite "occasional strains". South Africa remains the United States' largest trading partner in Africa as of 2019.

Foreign relations of South Africa during apartheid refers to the foreign relations of South Africa between 1948 and 1994. South Africa introduced apartheid in 1948, as a systematic extension of pre-existing racial discrimination laws. Initially the regime implemented an offensive foreign policy trying to consolidate South African hegemony over Southern Africa. These attempts had clearly failed by the late 1970s. As a result of its racism, occupation of Namibia and foreign interventionism in Angola, the country became increasingly isolated internationally.

The William M. (Mac) Thornberry National Defense Authorization Act for Fiscal Year 2021 is a United States federal law which specifies the budget, expenditures and policies of the U.S. Department of Defense (DOD) for fiscal year 2021. Analogous NDAAs have been passed annually for 59 years. The act is named in honor of Representative Mac Thornberry, who served as either the chair or the ranking member of the House Armed Services Committee. Thornberry retired from Congress at the end of the congressional session.

As a response to South Africa's apartheid policies, the international community adopted economic sanctions as a form of condemnation and pressure. Jamaica led the movement by being the first country to ban goods from apartheid South Africa in 1959.

The anti-apartheid movement was a worldwide effort to end South Africa's apartheid regime and its oppressive policies of racial segregation. The movement emerged after the National Party government in South Africa won the election of 1948 and enforced a system of racial segregation through legislation. Opposition to the apartheid system came from both within South Africa and the international community, in particular Great Britain and the United States. The anti-apartheid movement consisted of a series of demonstrations, economic divestment, and boycotts against South Africa. In the United States, anti-apartheid efforts were initiated primarily by nongovernmental human rights organizations. On the other hand, state and federal governments were reluctant to support the call for sanctions against South Africa due to a Cold War alliance with the country and profitable economic ties. The rift between public condemnation of apartheid and the U.S government's continued support of the South African government delayed efforts to negotiate a peaceful transfer to majority rule. Eventually, a congressional override of President Reagan's veto resulted in passage of the Comprehensive Anti-Apartheid Act in 1986. However, the extent to which the anti-apartheid movement contributed to the downfall of apartheid in 1994 remains under debate.