Sovereign immunity, or crown immunity, is a legal doctrine whereby a sovereign or state cannot commit a legal wrong and is immune from civil suit or criminal prosecution, strictly speaking in modern texts in its own courts. State immunity is a similar, stronger doctrine, that applies to foreign courts.

Legal immunity, or immunity from prosecution, is a legal status wherein an individual or entity cannot be held liable for a violation of the law, in order to facilitate societal aims that outweigh the value of imposing liability in such cases. Such legal immunity may be from criminal prosecution, or from civil liability, or both. The most notable forms of legal immunity are parliamentary immunity and witness immunity. One author has described legal immunity as "the obverse of a legal power":

A party has an immunity with respect to some action, object or status, if some other relevant party – in this context, another state or international agency, or citizen or group of citizens – has no (power) right to alter the party's legal standing in point of rights or duties in the specified respect. There is a wide range of legal immunities that may be invoked in the name of the right to rule. In international law, immunities may be created when states assert powers of derogation, as is permitted, for example, from the European Convention on Human Rights "in times of war or other public emergency." Equally familiar examples include the immunities against prosecution granted to representatives and government officials in pursuit of their duties. Such legal immunities may be suspect as potential violations of the rule of law, or regarded as quite proper, as necessary protections for the officers of the state in the rightful pursuit of their duties.

The Alien Tort Statute, also called the Alien Tort Claims Act (ATCA), is a section in the United States Code that gives federal courts jurisdiction over lawsuits filed by foreign nationals for torts committed in violation of international law. It was first introduced by the Judiciary Act of 1789 and is one of the oldest federal laws still in effect in the U.S.

Board of Trustees of the University of Alabama v. Garrett, 531 U.S. 356 (2001), was a United States Supreme Court case about Congress's enforcement powers under the Fourteenth Amendment to the United States Constitution. The Supreme Court decided that Title I of the Americans with Disabilities Act was unconstitutional, insofar as it allowed states to be sued by private citizens for money damages.

Hans v. Louisiana, 134 U.S. 1 (1890), was a decision of the United States Supreme Court determining that the Eleventh Amendment prohibits a citizen of a U.S. state to sue that state in a federal court. Citizens cannot bring suits against their own state for cases related to the federal constitution and federal laws. The court left open the question of whether a citizen may sue his or her state in state courts. That ambiguity was resolved in Alden v. Maine (1999), in which the Court held that a state's sovereign immunity forecloses suits against a state government in state court.

United States v. Reynolds, 345 U.S. 1 (1953), is a landmark legal case decided in 1953, which saw the formal recognition of the state secrets privilege, a judicially recognized extension of presidential power. The US Supreme Court confirmed that "the privilege against revealing military secrets ... is well established in the law of evidence".

The Protection of Lawful Commerce in Arms Act (PLCAA) is a U.S law, passed in 2005, that protects firearms manufacturers and dealers from being held liable when crimes have been committed with their products. Both arms manufacturers and dealers can still be held liable for damages resulting from defective products, breach of contract, criminal misconduct, and other actions for which they are directly responsible. However, they may be held liable for negligent entrustment if it is found that they had reason to believe a firearm was intended for use in a crime.

In the United States, qualified immunity is a legal principle of federal constitutional law that grants government officials performing discretionary (optional) functions immunity from lawsuits for damages unless the plaintiff shows that the official violated "clearly established statutory or constitutional rights of which a reasonable person would have known". It is comparable to sovereign immunity, though it protects government employees rather than the government itself. It is less strict than absolute immunity, which protects officials who "make reasonable but mistaken judgments about open legal questions", extending to "all [officials] but the plainly incompetent or those who knowingly violate the law". Qualified immunity applies only to government officials in civil litigation, and does not protect the government itself from suits arising from officials' actions.

Dolan v. United States Postal Service, 546 U.S. 481 (2006), was a case decided by the Supreme Court of the United States, involving the extent to which the United States Postal Service has sovereign immunity from lawsuits brought by private individuals under the Federal Tort Claims Act. The Court ruled that an exception to the FTCA that barred liability for the "negligent transmission of mail" did not apply to a claim for injuries caused when someone tripped over mail left by a USPS employee. Instead, the exception only applied to damage caused to the mail itself or that resulted from its loss or delay.

The Speech or Debate Clause is a clause in the United States Constitution. The clause states that "The Senators and Representatives" of Congress "shall in all Cases, except Treason, Felony, and Breach of the Peace, be privileged from Arrest during their attendance at the Session of their Respective Houses, and in going to and from the same; and for any Speech or Debate in either House, they shall not be questioned in any other Place."

Feres v. United States, 340 U.S. 135 (1950), combined three pending federal cases for a hearing in certiorari in which the Supreme Court of the United States held that the United States is not liable under the Federal Tort Claims Act for injuries to members of the armed forces sustained while on active duty and not on furlough and resulting from the negligence of others in the armed forces. The opinion is an extension of the English common-law concept of sovereign immunity.

Monell v. Department of Social Services, 436 U.S. 658 (1978), is an opinion given by the United States Supreme Court in which the Court overruled Monroe v. Pape by holding that a local government is a "person" subject to suit under Section 1983 of Title 42 of the United States Code: Civil action for deprivation of rights. Additionally, the Court held that §1983 claims against municipal entities must be based on implementation of a policy or custom.

The Federal Tort Claims Act ("FTCA") is a 1946 federal statute that permits private parties to sue the United States in a federal court for most torts committed by persons acting on behalf of the United States. Historically, citizens have not been able to sue the government — a doctrine referred to as sovereign immunity. The FTCA constitutes a limited waiver of sovereign immunity by the United States, permitting citizens to pursue some tort claims against the federal government. It was passed and enacted as a part of the Legislative Reorganization Act of 1946.

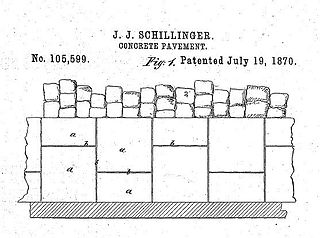

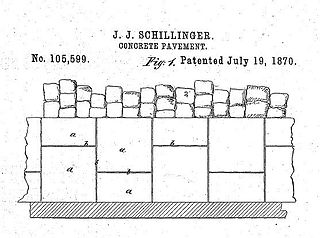

Schillinger v. United States, 155 U.S. 163 (1894), is a decision of the United States Supreme Court, holding that a suit for patent infringement cannot be entertained against the United States, because patent infringement is a tort and the United States has not waived sovereign immunity for intentional torts.

In United States law, absolute immunity is a type of sovereign immunity for government officials that confers complete immunity from criminal prosecution and suits for damages, so long as officials are acting within the scope of their duties. The Supreme Court of the United States has consistently held that government officials deserve some type of immunity from lawsuits for damages, and that the common law recognized this immunity. The Court reasons that this immunity is necessary to protect public officials from excessive interference with their responsibilities and from "potentially disabling threats of liability."

In United States law, the federal government as well as state and tribal governments generally enjoy sovereign immunity, also known as governmental immunity, from lawsuits. Local governments in most jurisdictions enjoy immunity from some forms of suit, particularly in tort. The Foreign Sovereign Immunities Act provides foreign governments, including state-owned companies, with a related form of immunity—state immunity—that shields them from lawsuits except in relation to certain actions relating to commercial activity in the United States. The principle of sovereign immunity in US law was inherited from the English common law legal maxim rex non potest peccare, meaning "the king can do no wrong." In some situations, sovereign immunity may be waived by law.

The California Government Claims Act sets forth the procedures that must be followed when filing a claim for money or damages against a governmental entity in the state of California. This includes state, county, and local entities, as well as their employees. The Government Claims Act is found in Division 3.6 of the Government Code, Govt. Code §§ 810 et seq.

United States v. Johnson, 481 U.S. 681 (1987), was a United States Supreme Court case in which the Court barred the widow of a serviceman killed while piloting a helicopter on a United States Coast Guard rescue mission from bringing her claim under the Federal Tort Claims Act. The decision was based upon the Supreme Court's holding in Feres v. United States (1950): "[T]he Government is not liable under the Federal Tort Claims Act for injuries to servicemen where the injuries arise out of or are in the course of activity incident to service."

Forrester v. White, 484 U.S. 219 (1988), was a case decided on by the United States Supreme Court. The case restricted judicial immunity in certain instances.

Franchise Tax Board of California v. Hyatt, 587 U.S. 230 (2019), was a United States Supreme Court case that determined that unless they consent, states have sovereign immunity from private suits filed against them in the courts of another state. The 5–4 decision overturned precedent set in a 1979 Supreme Court case, Nevada v. Hall. This was the third time that the litigants had presented their case to the Court, as the Court had already ruled on the issue in 2003 and 2016.