A green card, known officially as a permanent resident card, is an identity document which shows that a person has permanent residency in the United States. Green card holders are formally known as lawful permanent residents (LPRs). As of 2019, there are an estimated 13.9 million green card holders, of whom 9.1 million are eligible to become United States citizens. Approximately 18,700 of them serve in the U.S. Armed Forces.

The H-1B is a visa in the United States under the Immigration and Nationality Act, section 101(a)(15)(H), that allows U.S. employers to employ foreign workers in specialty occupations. A specialty occupation requires the application of specialized knowledge and a bachelor's degree or the equivalent of work experience. The duration of stay is three years, extendable to six years, after which the visa holder can reapply. Laws limit the number of H-1B visas that are issued each year. There exist congressionally mandated caps limiting the number of H-1B visas that can be issued each fiscal year, which is 65,000 visas, and an additional 20,000 set aside for those graduating with master’s degrees or higher from a U.S. college or university. An employer must sponsor individuals for the visa. USCIS estimates there are 583,420 foreign nationals on H-1B visas as of September 30, 2019. The number of issued H-1B visas have quadrupled since the first year these visas were issued in 1991. There were 206,002 initial and continuing H-1B visas issued in 2022.

In the United States, identity documents are typically the regional state-issued driver's license or identity card, while also the Social Security card and the United States passport card may serve as national identification. The United States passport itself also may serve as identification. There is, however, no official "national identity card" in the United States, in the sense that there is no federal agency with nationwide jurisdiction that directly issues an identity document to all US citizens for mandatory regular use.

An L-1 visa is a visa document used to enter the United States for the purpose of work in L-1 status. It is a non-immigrant visa, and is valid for a relatively short amount of time, from three months to five years, based on a reciprocity schedule. With extensions, the maximum stay is seven years.

TN status is a special non-immigrant classification of foreign nationals in the United States, which offers expedited work authorization to a citizen of Canada or a national of Mexico. It was created as a result of provisions of the North American Free Trade Agreement that mandated simplified entry and employment permission for certain professionals from each of the three NAFTA member states in the other member states. The provisions of NAFTA relevant to TN status were then carried over almost verbatim to the United States–Mexico–Canada Agreement that replaced NAFTA in 2020.

Parole, in the immigration laws of the United States, generally refers to official permission to enter and remain temporarily in the United States, under the supervision of the U.S. Department of Homeland Security (DHS), without formal admission, and while remaining an applicant for admission.

In the United States, Optional Practical Training (OPT) is a period during which undergraduate and graduate students with F-1 status who have completed or have been pursuing their degrees for one academic year are permitted by the United States Citizenship and Immigration Services (USCIS) to work for one year on a student visa towards getting practical training to complement their education. Foreign students currently enrolled at a U.S. university can receive full-time or part-time work authorization through Curricular Practical Training. In 2022, there were 171,635 OPT employment authorizations. In 2021, there were 115,651 new non-STEM OPT authorizations, a 105% increase from a decade ago.

U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services (USCIS) is an agency of the United States Department of Homeland Security (DHS) that administers the country's naturalization and immigration system. It is a successor to the Immigration and Naturalization Service (INS), which was dissolved by the Homeland Security Act of 2002 and replaced by three components within the DHS: USCIS, Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE), and Customs and Border Protection (CBP).

An H-2A visa allows a foreign national worker into the United States for temporary agricultural work. There are several requirements of the employer in regard to this visa. The H-2A temporary agricultural program establishes a means for agricultural employers who anticipate a shortage of domestic workers to bring non-immigrant foreign workers to the U.S. to perform agricultural labor or services of a temporary or seasonal nature. In 2015 there were approximately 140,000 total temporary agricultural workers under this visa program. Terms of work can be as short as a month or two or as long as 10 months in most cases, although there are some special procedures that allow workers to stay longer than 10 months. All of these workers are covered by U.S. wage laws, workers' compensation and other standards; additionally, temporary workers and their employers are subject to the employer and/or individual mandates under the Affordable Care Act. Because of concern that guest workers might be unfairly exploited, the U.S. Department of Labor Wage and Hour Division is especially vigilant in auditing and inspecting H-2A employers. H-2A employers are the only group of employers who are required to pay inbound and outbound transportation, free housing, and provide meals for their workers. H-2A agricultural employers are among the most heavily regulated and monitored employers in the United States. Unlike other guest worker programs, there is no cap on the number of H-2A visas allocated each year.

Visitors to the United States must obtain a visa from one of the U.S. diplomatic missions unless they are citizens of one of the visa-exempt or Visa Waiver Program countries.

An H-4 visa is a United States visa issued to dependent family members of H-1B, H-1B1, H-2A, H-2B, and H-3 visa holders to allow them to travel to the United States to accompany or reunite with the principal visa holder. A dependent family member is a spouse or unmarried child under the age of 21. If a dependent of an H-1B, H-1B1, H-2A, H-2B, or H-3 worker is already in the United States, they can apply for H-4 immigration status by filing Form I-539 for change of status with United States Citizenship and Immigration Services (USCIS).

A Form I-766 employment authorization document or EAD card, known popularly as a work permit, is a document issued by the United States Citizenship and Immigration Services (USCIS) that provides temporary employment authorization to noncitizens in the United States.

The United States passport card is an optional national identity card and a travel document issued by the U.S. federal government in the size of a credit card. Like a U.S. passport book, the passport card is only issued to U.S. citizens and U.S. nationals exclusively by the U.S. Department of State. The passport card allows its holders to travel by domestic air flights within the U.S., and to travel by land and sea within North America. However, the passport card cannot be used for international air travel. US passport cards are used to verify identity and US citizenship. The requirements to attain the passport card are identical to the passport book and compliant to the standards for identity documents set by the REAL ID Act.

The Security Through Regularized Immigration and a Vibrant Economy Act of 2007 or STRIVE Act of 2007 is proposed United States legislation designed to address the problem of illegal immigration, introduced into the United States House of Representatives. Its supporters claim it would toughen border security, increase enforcement of and criminal penalties for illegal immigration, and establish an employment verification system to identify illegal aliens working in the United States. It would also establish new programs for both illegal aliens and new immigrant workers to achieve legal citizenship. Critics allege that the bill would turn law enforcement agencies into social welfare agencies as it would not allow CBP to detain illegal immigrants that are eligible for Z-visas and would grant amnesty to millions of illegal aliens with very few restrictions.

E-Verify is a United States Department of Homeland Security (DHS) website that allows businesses to determine the eligibility of their employees, both U.S. and foreign citizens, to work in the United States. The site was originally established in 1996 as the Basic Pilot Program to prevent companies from hiring people who had violated immigration laws and entered the United States illegally. In August 2007, the DHS started requiring all federal contractors and vendors to use E-Verify. The Internet-based program is free and maintained by the United States government. While federal law does not mandate use of E-Verify for non-federal employees, some states have mandated use of E-Verify or similar programs, while others have discouraged the program.

Temporary protected status (TPS) is given by the United States government to eligible nationals of designated countries, as determined by the Secretary of Homeland Security, who are present in the United States. In general, the Secretary of Homeland Security may grant temporary protected status to people already present in the United States who are nationals of a country experiencing ongoing armed conflict, an environmental disaster, or any temporary or extraordinary conditions that would prevent the foreign national from returning safely and assimilating into their duty. Temporary protected status allows beneficiaries to live and, in some cases, work in the United States for a limited amount of time. As of March 2022, there are more than 400,000 foreign nationals in Temporary Protected Status.

Form I-129, Petition for a Nonimmigrant Worker is a form submitted to the United States Citizenship and Immigration Services used by employers or prospective employers to obtain a worker on a nonimmigrant visa status. Form I-129 is used to either file for a new status or a change of status, such as new, continuing or changed employer or title; or an amendment to the original application. Approval of the form makes the worker eligible to start or continue working at the job if already in the United States. If the worker is not already in the United States, an approved Form I-129 may be used to submit a visa application associated with that status. The form is 36 pages long and the instructions for the form are 29 pages long. It is one of the many USCIS immigration forms.

The United States Citizenship and Immigration Services (USCIS) issues a number of forms for people to submit to them relating to immigrant and non-immigrant visa statuses. These forms begin with the letter "I". None of the forms directly grants a United States visa, but approval of these forms may provide authorization for staying or extending one's stay in the United States as well as authorization for work. Some United States visas require an associated approved USCIS immigration form to be submitted as part of the application.

Special Immigrant Juvenile Status (SIJS) is a special way for minors currently in the United States to adjust status to that of Lawful Permanent Resident despite unauthorized entry or unlawful presence in the United States, that might usually make them inadmissible to the United States and create bars to Adjustment of Status. The key criterion for SIJS is abuse, neglect, or abandonment by one or both parents.

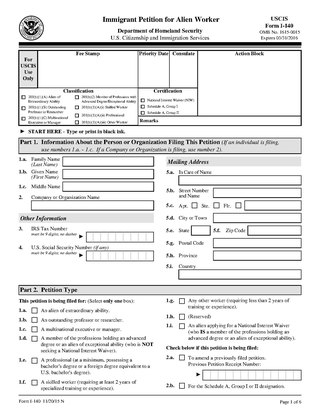

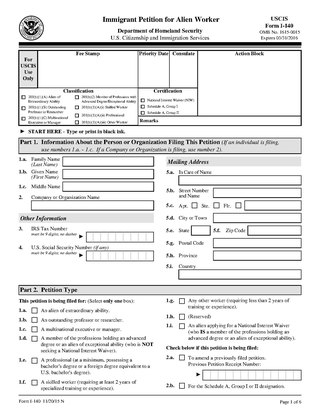

Form I-140, Immigrant Petition for Alien Worker is a form submitted to the United States Citizenship and Immigration Service (USCIS) by a prospective employer to petition an alien to work in the US on a permanent basis. This is done in the case when the worker is deemed extraordinary in some sense or when qualified workers do not exist in the US. The employer who files is called the petitioner, and the alien employee is called the beneficiary; these two can coincide in the case of a self-petitioner. The form is 6 pages long with a separate 10-page instructions document as of 2016. It is one of the USCIS immigration forms.