Related Research Articles

Divorce is the process of terminating a marriage or marital union. Divorce usually entails the canceling or reorganising of the legal duties and responsibilities of marriage, thus dissolving the bonds of matrimony between a married couple under the rule of law of the particular country or state. It can be said to be a legal dissolution of a marriage by a court or other competent body. It is the legal process of ending a marriage.

Alimony, also called aliment (Scotland), maintenance, spousal support and spouse maintenance (Australia), is a legal obligation on a person to provide financial support to their spouse before or after marital separation or divorce. The obligation arises from the divorce law or family law of each country. In most jurisdictions, it is distinct from child support, where, after divorce, one parent is required to contribute to the support of their children by paying money to the child's other parent or guardian.

Legal separation is a legal process by which a married couple may formalize a de facto separation while remaining legally married. A legal separation is granted in the form of a court order. In cases where children are involved, a court order of legal separation often makes child custody arrangements, specifying sole custody or shared parenting, as well as child support. Some couples obtain a legal separation as an alternative to a divorce, based on moral or religious objections to divorce.

Annulment is a legal procedure within secular and religious legal systems for declaring a marriage null and void. Unlike divorce, it is usually retroactive, meaning that an annulled marriage is considered to be invalid from the beginning almost as if it had never taken place. In legal terminology, an annulment makes a void marriage or a voidable marriage null.

In a culture where only monogamous relationships are legally recognized, bigamy is the act of entering into a marriage with one person while still legally married to another. A legal or de facto separation of the couple does not alter their marital status as married persons. In the case of a person in the process of divorcing their spouse, that person is taken to be legally married until such time as the divorce becomes final or absolute under the law of the relevant jurisdiction. Bigamy laws do not apply to couples in a de facto or cohabitation relationship, or that enter such relationships when one is legally married. If the prior marriage is for any reason void, the couple is not married, and hence each party is free to marry another without falling foul of the bigamy laws.

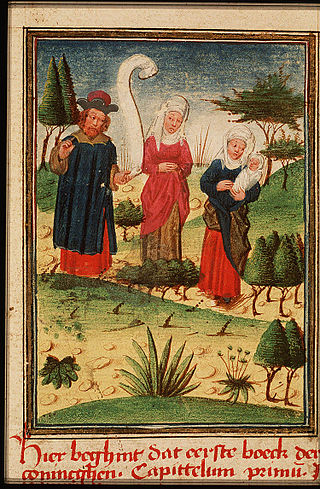

In many traditions and statutes of civil or religious law, the consummation of a marriage, often called simply consummation, is the first act of sexual intercourse between two people, following their marriage to each other. The definition of consummation usually refers to penile-vaginal sexual penetration, but some religious doctrines hold that there is an additional requirement that no contraception must be used. In this sense, "a marriage is consummated only if the conjugal act performed deposits semen in the vagina".

No-fault divorce is the dissolution of a marriage that does not require a showing of wrongdoing by either party. Laws providing for no-fault divorce allow a family court to grant a divorce in response to a petition by either party of the marriage without requiring the petitioner to provide evidence that the defendant has committed a breach of the marital contract.

Robinhood Ferdinand Cariño Padilla, known professionally as Robin Padilla, is a Filipino actor, director and politician. He is known as the "Bad Boy" of Philippine cinema for portraying anti-hero gangster roles in films such as Anak ni Baby Ama (1990), Grease Gun Gang (1992), Bad Boy (1990), and Bad Boy 2 (1992). He has also been dubbed the "Prince of Action" in Philippine cinema.

Covenant marriage is a legally distinct kind of marriage in three states of the United States, in which the marrying spouses agree to obtain pre-marital counseling and accept more limited grounds for later seeking divorce. Louisiana became the first state to pass a covenant marriage law in 1997; shortly afterwards, Arkansas and Arizona followed suit. Since its inception, very few couples in those states have married under covenant marriage law.

Grounds for divorce are regulations specifying the circumstances under which a person will be granted a divorce. Each state in the United States has its own set of grounds. A person must state the reason they want a divorce at a divorce trial and be able to prove that this reason is well-founded. Several states require that the couple must live apart for several months before being granted a divorce. However, living apart is not accepted as grounds for a divorce in many states.

Divorce law, the legal provisions for the dissolution of marriage, varies widely across the globe, reflecting diverse legal systems and cultural norms. Most nations allow for residents to divorce under some conditions except the Philippines and the Vatican City, an ecclesiastical sovereign city-state, which has no procedure for divorce. In these two countries, laws only allow annulment of marriages.

Marriage in the United States is a legal, social, and religious institution. The marriage age in the United States is set by each state and territory, either by statute or the common law applies. An individual may marry in the United States as of right, without parental consent or other authorization, on reaching 18 years of age in all states except in Nebraska, where the general marriage age is 19, and Mississippi, where the general marriage age is 21. In Puerto Rico the general marriage age is also 21. In all these jurisdictions, these are also the ages of majority. In Alabama, however, the age of majority is 19, while the general marriage age is 18. Most states also set a lower age at which underage persons are able to marry with parental and/or judicial consent. Marriages where one partner is less than 18 years of age are commonly referred to as child or underage marriages.

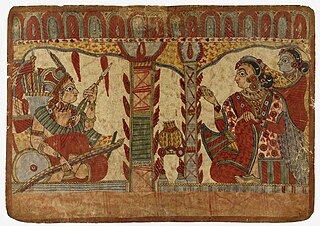

The Hindu Marriage Act (HMA) is an act of the Parliament of India enacted in 1955 which was passed on 18 May. Three other important acts were also enacted as part of the Hindu Code Bills during this time: the Hindu Succession Act (1956), the Hindu Minority and Guardianship Act (1956), the Hindu Adoptions and Maintenance Act (1956).

In England and Wales, divorce is allowed under the Divorce, Dissolution and Separation Act 2020 on the ground that the marriage has irretrievably broken down without having to prove fault or separation.

Debate has occurred throughout Asia over proposals to legalize same-sex marriage as well as civil unions.

Divorce in Francoist Spain and the democratic transition were illegal. While divorce had been legal during the Second Spanish Republic, Franco began to overturn these laws by March 1938. In 1945, the legislation embodied in his Fuero de los Españoles established that marriage was an indissoluble union. Divorce was still possible in Spain through the Catholic Church as a result of Pauline privilege or petrino. Marriages, primarily for the rich, could also be annulled through ecclesiastical tribunals. The Catholic Church was vigorously opposed to divorces, whether on religious or civil grounds.

Shari'ah or Islamic law is partially implemented in the legal system of the Philippines and is applicable only to Muslims. Shari'ah courts in the country are under the supervision of the Supreme Court of the Philippines.

Secularism in the Philippines concerns the relationship of the Philippine government with religion. Officially the Philippines is a secular state, but religious institutions and religion play a significant role in the country's political affairs. Legal pluralism also persist with the application of Islamic personal laws for the country's Muslim population.

The Code of Muslim Personal Laws is a legislation in the Philippines covering Muslims in the country which came into effect through Presidential Decree No. 1083 in 1977.

The Philippines does not legally recognize same-sex unions, either in the form of marriage or civil unions. The Family Code of the Philippines defines only recognizes marriages between "a man and a woman". The 1987 Constitution itself does not mention the legality of same-sex unions or has explicit restrictions on marriage that would bare same-sex partners to enter into such arrangement.

References

- ↑ published, The Week Staff (April 9, 2019). "Countries where divorce is illegal". The Week . Retrieved May 25, 2024.

- ↑ Santos, Ana (June 25, 2015). "The Only Country in the World That Bans Divorce". The Atlantic. Retrieved April 13, 2023.

- ↑ "The Philippines: a global holdout in divorce". New Internationalist. July 5, 2011. Archived from the original on April 15, 2023. Retrieved April 15, 2023.

- ↑ Hundley, Tom; Santos, Ana (January 19, 2015). "The Last Country in the World Where Divorce Is Illegal". Foreign Policy. Retrieved April 15, 2023.

- 1 2 3 4 Juco, Jorge (April 1966). "Fault, Consent and Breakdown-The Sociology of Divorce Legislation in the Philippines" (PDF). Philippine Sociological Review: 67–76. Retrieved April 13, 2023.

- ↑ "House okays on final reading bill legalizing divorce". Manila Standard.

- 1 2 3 4 Foja, Alnie (August 2017). Reintroducing Absolute Divorce in the Philippines & Thoughts on the Divorce Bill (Monograph Series No. 2 ed.). UP Diliman Gender Office. Retrieved April 13, 2023.

- 1 2 3 "Women's Priority Legislative Agenda for the 18th Congress: Adopting Divorce in the Family Code" (PDF). Philippine Commission on Women. Retrieved April 13, 2023.

- ↑ "Philippine President Arroyo Opposes Constitutional Amendments, Divorce". Wall Street Journal. July 6, 2001. Retrieved April 15, 2023.

- ↑ "Arroyo opposes divorce bill". News24. March 19, 2005. Retrieved April 15, 2023.

- 1 2 Beltran, Jill (August 19, 2010). "Aquino won't support divorce (12:59 p.m.)". SunStar. Retrieved April 13, 2023.

- ↑ "Divorce? No way, stresses Philippine government". The Korea Herald. January 7, 2013. Retrieved April 13, 2023.

- ↑ Salaverria, Leila (March 20, 2018). "Duterte opposed to divorce – Roque". Philippine Daily Inquirer. Retrieved April 15, 2023.

- ↑ Patag, Kristine Joy (March 19, 2022). "Marcos open to divorce, 'but don't make it easy'". The Philippine Star. Retrieved April 15, 2023.

- 1 2 Pulta, Benjamin (June 8, 2021). "SC rules in favor of Ibaloi heirs claim on father's estate". Philippine News Agency. Retrieved April 13, 2023.

- ↑ "Shariah Law and the Code of Muslim Personal Laws". Institute for Autonomy and Governance. Sun Star Davao. January 21, 2015. Retrieved April 15, 2023.

- ↑ Eugenio, Ara (February 14, 2024). "Converting to Islam falsely touted as 'pathway to divorce' in Catholic-majority Philippines". AFP Fact Check. Agence France-Presse. Retrieved March 9, 2024.

- ↑ "Family Code of the Philippines". Archived from the original on August 19, 2000. Retrieved September 6, 2006.

- ↑ "Republic of the Philippines vs Orbeceido". Lawphil Project. Arellano Law. Retrieved January 26, 2018.

- ↑ Quismoro, Elson (February 23, 2023). "Many marriages are 'mistakes', says pro-divorce solon". Manila Bulletin. Retrieved April 15, 2023.

- ↑ Torres, Sherrie Ann (July 12, 2022). "Hontiveros files 'no-fault' divorce bill amid church objection". ABS-CBN News. Retrieved April 13, 2023.

- ↑ Cruz, RG (February 20, 2018). "House panel drops chronic unhappiness, no-fault provision in divorce bill". ABS-CBN News. Retrieved April 13, 2023.

- ↑ Felipe, Cecille Suerte (September 20, 2023). "Senate panel OKs absolute divorce bill". The Philippine Star . Retrieved May 16, 2024.

- ↑ Cervantes, Filane Mike (May 16, 2024). "Absolute divorce bill hurdles 2nd reading in House". Philippine News Agency . Retrieved May 16, 2024.

- ↑ Garcia, Nick (May 16, 2024). "House approves divorce bill on second reading". The Philippine Star . Retrieved May 16, 2024.

- ↑ Lalu, Gabriel Pabico (May 15, 2024). "House approves divorce bill on 2nd reading". Philippine Daily Inquirer . Retrieved May 16, 2024.

- ↑ Cruz, Maricel (May 15, 2024). "Bill on 'absolute divorce' gets House vote on second reading". Manila Standard . Retrieved May 16, 2024.

- 1 2 Patinio, Ferdinand (September 18, 2019). "No need for divorce, legal methods available for couples: CBCP". Philippine News Agency. Retrieved April 16, 2023.

- ↑ Rosario, Ben (August 20, 2021). "Oppositors confident 'unconstitutional' divorce bill will not get Lower House nod". Manila Bulletin. Retrieved April 16, 2023.

- ↑ Diaz, Jess (March 16, 2018). "'Divorce law will violate Constitution'". Philstar.com. The Philippine Star. Retrieved April 16, 2023.

- ↑ Fides, Agenzia (September 20, 2019). "Bishops: No to bills on divorce, anti-constitutional and anti-family - Agenzia Fides". Agenzia Fides. Retrieved April 16, 2023.

- ↑ "Our Right To Self-determination: Pilipina's Position On The Issues Of Divorce And Abortion" (PDF). Friedrich-Ebert-Stiftung. 2000. Retrieved April 16, 2023.

- ↑ "CBCP: Divorce bill 'anti-marriage and anti-family'". CNN Philippines. February 23, 2018. Archived from the original on February 25, 2018. Retrieved April 16, 2023.

- ↑ Medenilla, Samuel (September 22, 2019). "CBCP: Divorce unconstitutional in PHL; legal methods available". Business Mirror. Retrieved April 16, 2023.

- ↑ "CBCP Position against the Divorce Bill and against the Decriminalization of Adultery and Concubinage". CBCP Online. Retrieved April 16, 2023.

- ↑ Mendoza, John (May 23, 2024). "CBCP hits House for approving divorce bill". Catholic Bishops' Conference of the Philippines . Retrieved May 23, 2024.

- ↑ "For they are no longer two, but one". Iglesia Ni Cristo. November 23, 2022. Retrieved April 16, 2023.

- ↑ Alignay, Moses (September 30, 2021). "What Does the Bible Say About Divorce?". INC Media. Retrieved April 16, 2023.

- ↑ Escareal-Go, Chiqui (2014). "Driven to Survive: Four Filipino Women CEOs' Stories on Separation or Annulment". Philippine Social Sciences Review: 52. Retrieved April 16, 2023.

- ↑ "Is the Philippines Ready for Divorce?". Philippine Daily Inquirer. July 9, 2011. Retrieved April 16, 2023.