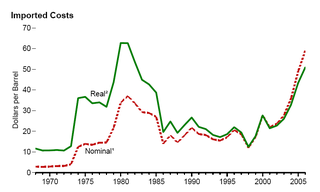

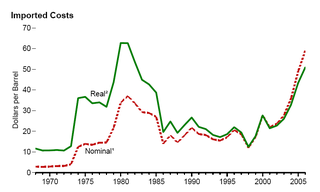

A drop in oil production in the wake of the Iranian Revolution led to an energy crisis in 1979. Although the global oil supply only decreased by approximately four percent, the oil markets' reaction raised the price of crude oil drastically over the next 12 months, more than doubling it to $39.50 per barrel ($248/m3). The sudden increase in price was connected with fuel shortages and long lines at gas stations similar to the 1973 oil crisis.

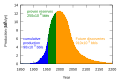

The Hubbert peak theory says that for any given geographical area, from an individual oil-producing region to the planet as a whole, the rate of petroleum production tends to follow a bell-shaped curve. It is one of the primary theories on peak oil.

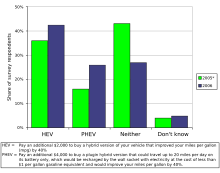

Peak oil is the theorized point in time when the maximum rate of global oil production will occur, after which oil production will begin an irreversible decline. The primary concern of peak oil is that global transportation heavily relies upon the use of gasoline and diesel fuel. Switching transportation to electric vehicles, biofuels, or more fuel-efficient forms of travel may help reduce oil demand.

Colin J. Campbell was a British petroleum geologist who predicted that oil production would peak by 2007. He claimed the consequences of this are uncertain but drastic, due to the world's dependency on fossil fuels for the vast majority of its energy. His theories have received wide attention but are disputed and have not significantly changed governmental energy policies at this time. To deal with declining global oil production, he proposed the Rimini protocol.

From the mid-1980s to September 2003, the inflation-adjusted price of a barrel of crude oil on NYMEX was generally under US$25/barrel in 2008 dollars. During 2003, the price rose above $30, reached $60 by 11 August 2005, and peaked at $147.30 in July 2008. Commentators attributed these price increases to many factors, including Middle East tension, soaring demand from China, the falling value of the U.S. dollar, reports showing a decline in petroleum reserves, worries over peak oil, and financial speculation.

Oil depletion is the decline in oil production of a well, oil field, or geographic area. The Hubbert peak theory makes predictions of production rates based on prior discovery rates and anticipated production rates. Hubbert curves predict that the production curves of non-renewing resources approximate a bell curve. Thus, according to this theory, when the peak of production is passed, production rates enter an irreversible decline.

The Argentine energy crisis was a natural gas supply shortage experienced by Argentina in 2004. After the recession triggered by the Argentine economic crisis (1999-2002), Argentina's energy demands grew quickly as industry recovered, but extraction and transportation of natural gas, a cheap and relatively abundant fossil fuel, did not match the surge.

Energía Argentina Sociedad Anónima, mostly known for its acronym ENARSA, is a state owned company in Argentina. It is engaged in the exploitation of petroleum and natural gas, and the production, industrialization, transport and trade of these and of electricity.

The energy industry is the totality of all of the industries involved in the production and sale of energy, including fuel extraction, manufacturing, refining and distribution. Modern society consumes large amounts of fuel, and the energy industry is a crucial part of the infrastructure and maintenance of society in almost all countries.

The price of oil, or the oil price, generally refers to the spot price of a barrel of benchmark crude oil—a reference price for buyers and sellers of crude oil such as West Texas Intermediate (WTI), Brent Crude, Dubai Crude, OPEC Reference Basket, Tapis crude, Bonny Light, Urals oil, Isthmus, and Western Canadian Select (WCS). Oil prices are determined by global supply and demand, rather than any country's domestic production level.

Energy security is the association between national security and the availability of natural resources for energy consumption. Access to cheaper energy has become essential to the functioning of modern economies. However, the uneven distribution of energy supplies among countries has led to significant vulnerabilities. International energy relations have contributed to the globalization of the world leading to energy security and energy vulnerability at the same time.

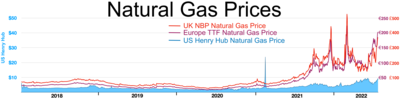

Peak gas is the point in time when the maximum global natural gas production rate will be reached, after which the rate of production will enter its terminal decline. Although demand is peaking in the United States and Europe, it continues to rise globally due to consumers in Asia, especially China. Natural gas is a fossil fuel formed from plant matter over the course of millions of years. Natural gas derived from fossil fuels is a non-renewable energy source; however, methane can be renewable in other forms such as biogas. Peak coal was in 2013, and peak oil is forecast to occur before peak gas. One forecast is for natural gas demand to peak in 2035.

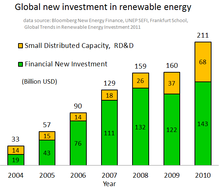

Fossil fuel phase-out is the gradual reduction of the use and production of fossil fuels to zero, to reduce deaths and illness from air pollution, limit climate change, and strengthen energy independence. It is part of the ongoing renewable energy transition, but is being hindered by fossil fuel subsidies.

Hydrocarbon economy is a term referencing the global hydrocarbon industry and its relationship to world markets. Energy used mostly comes from three hydrocarbons: petroleum, coal, and natural gas. Hydrocarbon economy is often used when talking about possible alternatives like the hydrogen economy.

Petroleum has been a major industry in the United States since the 1859 Pennsylvania oil rush around Titusville, Pennsylvania. Commonly characterized as "Big Oil", the industry includes exploration, production, refining, transportation, and marketing of oil and natural gas products. The leading crude oil-producing areas in the United States in 2023 were Texas, followed by the offshore federal zone of the Gulf of Mexico, North Dakota and New Mexico.

Electricity in Pakistan is generated, transmitted and distributed by two vertically integrated public sector companies, first one being Water and Power Development Authority (WAPDA) responsible for the production of hydroelectricity and its supply to the consumers by electricity distribution companies (DISCOS) under the Pakistan Electric Power Company (PEPCO) being the other integrated company. Currently, there are 12 distribution companies and a National Transmission And Dispatch Company (NTDC) which are all in the public sector except Karachi Electric in the city of Karachi and its surrounding areas. There are around 42 independent power producers (IPPs) that contribute significantly in electricity generation in Pakistan.

Russia supplies a significant volume of fossil fuels to other European countries. In 2021, it was the largest exporter of oil and natural gas to the European Union, (90%) and 40% of gas consumed in the EU came from Russia.

The 1970s energy crisis occurred when the Western world, particularly the United States, Canada, Western Europe, Australia, and New Zealand, faced substantial petroleum shortages as well as elevated prices. The two worst crises of this period were the 1973 oil crisis and the 1979 energy crisis, when, respectively, the Yom Kippur War and the Iranian Revolution triggered interruptions in Middle Eastern oil exports.

A global energy crisis began in the aftermath of the COVID-19 pandemic in 2021, with much of the globe facing shortages and increased prices in oil, gas and electricity markets. The crisis was caused by a variety of economic factors, including the rapid post-pandemic economic rebound that outpaced energy supply, and escalated into a widespread global energy crisis following the Russian invasion of Ukraine. The price of natural gas reached record highs, and as a result, so did electricity in some markets. Oil prices hit their highest level since 2008.

The 2021–2022 global energy crisis has caused varying effects in different parts of the world.