Triple oppression, also called double jeopardy, Jane Crow, or triple exploitation, is a theory developed by black socialists in the United States, such as Claudia Jones. The theory states that a connection exists between various types of oppression, specifically classism, racism, and sexism. It hypothesizes that all three types of oppression need to be overcome at once.

Anarcha-feminism, also known as anarchist feminism or anarcho-feminism, is a system of analysis which combines the principles and power analysis of anarchist theory with feminism. It closely resembles intersectional feminism. Anarcha-feminism generally posits that patriarchy and traditional gender roles as manifestations of involuntary coercive hierarchy should be replaced by decentralized free association. Anarcha-feminists believe that the struggle against patriarchy is an essential part of class conflict and the anarchist struggle against the state and capitalism. In essence, the philosophy sees anarchist struggle as a necessary component of feminist struggle and vice versa. L. Susan Brown claims that "as anarchism is a political philosophy that opposes all relationships of power, it is inherently feminist".

Identity politics is politics based on a particular identity, such as race, nationality, religion, gender, sexual orientation, social background, caste, and social class. The term could also encompass other social phenomena which are not commonly understood as exemplifying identity politics, such as governmental migration policy that regulates mobility based on identities, or far-right nationalist agendas of exclusion of national or ethnic others. For this reason, Kurzwelly, Pérez and Spiegel, who discuss several possible definitions of the term, argue that it is an analytically imprecise concept.

Liberal feminism, also called mainstream feminism, is a main branch of feminism defined by its focus on achieving gender equality through political and legal reform within the framework of liberal democracy and informed by a human rights perspective. It is often considered culturally progressive and economically center-right to center-left. As the oldest of the "Big Three" schools of feminist thought, liberal feminism has its roots in 19th century first-wave feminism seeking recognition of women as equal citizens, focusing particularly on women's suffrage and access to education, the effort associated with 19th century liberalism and progressivism. Liberal feminism "works within the structure of mainstream society to integrate women into that structure." Liberal feminism places great emphasis on the public world, especially laws, political institutions, education and working life, and considers the denial of equal legal and political rights as the main obstacle to equality. As such liberal feminists have worked to bring women into the political mainstream. Liberal feminism is inclusive and socially progressive, while broadly supporting existing institutions of power in liberal democratic societies, and is associated with centrism and reformism. Liberal feminism tends to be adopted by white middle-class women who do not disagree with the current social structure; Zhang and Rios found that liberal feminism with its focus on equality is viewed as the dominant and "default" form of feminism. Liberal feminism actively supports men's involvement in feminism and both women and men have always been active participants in the movement; progressive men had an important role alongside women in the struggle for equal political rights since the movement was launched in the 19th century.

Marxist feminism is a philosophical variant of feminism that incorporates and extends Marxist theory. Marxist feminism analyzes the ways in which women are exploited through capitalism and the individual ownership of private property. According to Marxist feminists, women's liberation can only be achieved by dismantling the capitalist systems in which they contend much of women's labor is uncompensated. Marxist feminists extend traditional Marxist analysis by applying it to unpaid domestic labor and sex relations.

Socialist feminism rose in the 1960s and 1970s as an offshoot of the feminist movement and New Left that focuses upon the interconnectivity of the patriarchy and capitalism. However, the ways in which women's private, domestic, and public roles in society has been conceptualized, or thought about, can be traced back to Mary Wollstonecraft's A Vindication of the Rights of Woman (1792) and William Thompson's utopian socialist work in the 1800s. Ideas about overcoming the patriarchy by coming together in female groups to talk about personal problems stem from Carol Hanisch. This was done in an essay in 1969 which later coined the term 'the personal is political.' This was also the time that second wave feminism started to surface which is really when socialist feminism kicked off. Socialist feminists argue that liberation can only be achieved by working to end both the economic and cultural sources of women's oppression.

Intersectionality is a sociological analytical framework for understanding how groups' and individuals' social and political identities result in unique combinations of discrimination and privilege. Examples of these factors include gender, caste, sex, race, ethnicity, class, sexuality, religion, disability, height, age, weight and physical appearance. These intersecting and overlapping social identities may be both empowering and oppressing. However, little good-quality quantitative research has been done to support or undermine the practical uses of intersectionality.

Black feminism is a branch of feminism that focuses on the African-American woman's experiences and recognizes the intersectionality of racism and sexism. Black feminism philosophy centers on the idea that "Black women are inherently valuable, that [Black women's] liberation is a necessity not as an adjunct to somebody else's but because of our need as human persons for autonomy."

The Combahee River Collective (CRC) was a Black feminist lesbian socialist organization active in Boston, Massachusetts from 1974 to 1980. The Collective argued that both the white feminist movement and the Civil Rights Movement were not addressing their particular needs as Black women and more specifically as Black lesbians. Racism was present in the mainstream feminist movement, while Delaney and Manditch-Prottas argue that much of the Civil Rights Movement had a sexist and homophobic reputation.

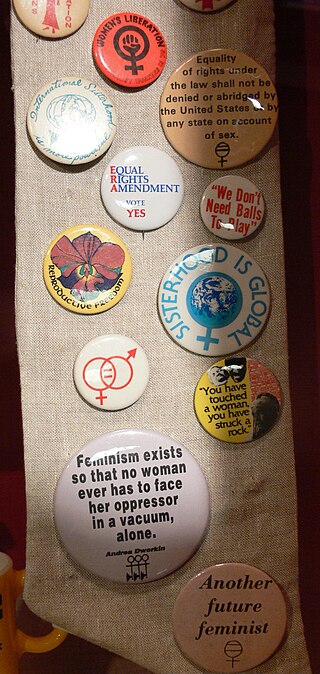

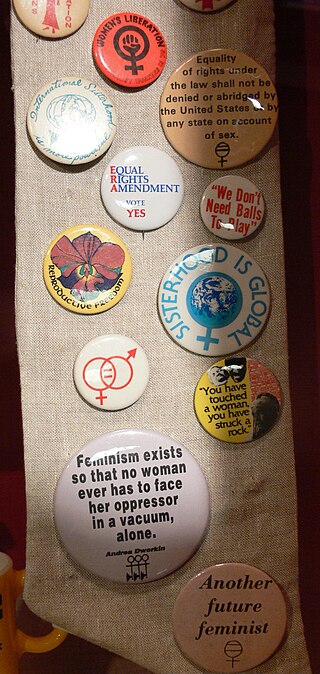

A variety of movements of feminist ideology have developed over the years. They vary in goals, strategies, and affiliations. They often overlap, and some feminists identify themselves with several branches of feminist thought.

The Third World Women's Alliance (TWWA) was a revolutionary socialist organization for women of color active in the United States from 1968 to 1980. It aimed at ending capitalism, racism, imperialism, and sexism and was one of the earliest groups advocating for an intersectional approach to women's oppression. Members of the TWWA argued that women of color faced a "triple jeopardy" of race, gender, and class oppression. The TWWA worked to address these intersectional issues, internationally and domestically, specifically focusing much of their efforts in Cuba. Though the organization's roots lay in the black civil rights movement, it soon broadened its focus to include women of color in the US and developing nations.

Marxism and the Oppression of Women: Toward a Unitary Theory is a book by the sociologist Lise Vogel that is considered an important contribution to Marxist Feminism. Vogel surveys Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels's comments on the causes of women's oppression, examines how socialist movements in Europe and in the United States have addressed women's oppression, and argues that women's oppression should be understood in terms of women's role in social reproduction and in particular in reproducing labor power.

Ecofeminism is a branch of feminism and political ecology. Ecofeminist thinkers draw on the concept of gender to analyse the relationships between humans and the natural world. The term was coined by the French writer Françoise d'Eaubonne in her book Le Féminisme ou la Mort (1974). Ecofeminist theory asserts a feminist perspective of Green politics that calls for an egalitarian, collaborative society in which there is no one dominant group. Today, there are several branches of ecofeminism, with varying approaches and analyses, including liberal ecofeminism, spiritual/cultural ecofeminism, and social/socialist ecofeminism. Interpretations of ecofeminism and how it might be applied to social thought include ecofeminist art, social justice and political philosophy, religion, contemporary feminism, and poetry.

Lise Vogel is a feminist sociologist and art historian from the United States. An influential Marxist-feminist theoretician, she is recognised for being one of the main founders of the Social Reproduction Theory. She also participated in the civil rights and the women's liberation movements in organisations such as the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC) in Mississippi and Bread & Roses in Boston. In her earlier career as an art historian, she was one of the first to try to develop a feminist perspective on Art History.

Ni una menos is a Latin American fourth-wave grassroots feminist movement, which started in Argentina and has spread across several Latin American countries, that campaigns against gender-based violence. This mass mobilization comes as a response to various systemic issues that proliferate violence against women. In its official website, Ni una menos defines itself as a "collective scream against machista violence." The campaign was started by a collective of Argentine female artists, journalists and academics, and has grown into "a continental alliance of feminist forces". Social media was an essential factor in the propagation of the Ni Una Menos movement to other countries and regions. The movement regularly holds protests against femicides, but has also touched on topics such as gender roles, sexual harassment, gender pay gap, sexual objectification, legality of abortion, sex workers' rights and transgender rights.

Fourth-wave feminism is a feminist movement that began around the early 2010s and is characterized by a focus on the empowerment of women, the use of Internet tools, and intersectionality. The fourth wave seeks greater gender equality by focusing on gendered norms and the marginalization of women in society.

Multiracial feminist theory is promoted by women of color (WOC), including Black, Latina, Asian, Native American, and anti-racist white women. In 1996, Maxine Baca Zinn and Bonnie Thornton Dill wrote “Theorizing Difference from Multiracial Feminism," a piece emphasizing intersectionality and the application of intersectional analysis within feminist discourse.

White feminism is a term which is used to describe expressions of feminism which are perceived as focusing on white women but are perceived as failing to address the existence of distinct forms of oppression faced by ethnic minority women and women lacking other privileges. Whiteness is crucial in structuring the lived experiences of white women across a variety of contexts. The term has been used to label and criticize theories that are perceived as focusing solely on gender-based inequality. Primarily used as a derogatory label, "white feminism" is typically used to reproach a perceived failure to acknowledge and integrate the intersection of other identity attributes into a broader movement which struggles for equality on more than one front. In white feminism, the oppression of women is analyzed through a single-axis framework, consequently erasing the identity and experiences of ethnic minority women the space. The term has also been used to refer to feminist theories perceived to focus more specifically on the experience of white, cisgender, heterosexual, able-bodied women, and in which the experiences of women without these characteristics are excluded or marginalized. This criticism has predominantly been leveled against the first waves of feminism which were seen as centered around the empowerment of white middle-class women in Western societies.

Tithi Bhattacharya is Associate Professor of South Asian history at Purdue University. She is a prominent Marxist feminist and one of the national organizers of the International Women's Strike on March 8, 2017. Bhattacharya is a vocal advocate of Palestinian rights and Boycott, Divestment and Sanctions (BDS).

Feminism and racism are highly intertwined concepts in intersectional theory, focusing on the ways in which women of color in the Western World experience both sexism and racism.