The Free Exercise Clause accompanies the Establishment Clause of the First Amendment to the United States Constitution. The Establishment Clause and the Free Exercise Clause together read:

Congress shall make no law respecting an establishment of religion, or prohibiting the free exercise thereof...

Employment Division, Department of Human Resources of Oregon v. Smith, 494 U.S. 872 (1990), is a United States Supreme Court case that held that the state could deny unemployment benefits to a person fired for violating a state prohibition on the use of peyote even though the use of the drug was part of a religious ritual. Although states have the power to accommodate otherwise illegal acts performed in pursuit of religious beliefs, they are not required to do so.

Becket, also known as the Becket Fund for Religious Liberty, is a non-profit public interest law firm based in Washington, D.C., that describes its mission as "defending the freedom of religion of people of all faiths". Becket promotes accommodationism and is active in the judicial system, the media, and in education.

Neil McGill Gorsuch is an American jurist who serves as an associate justice of the Supreme Court of the United States. He was nominated by President Donald Trump on January 31, 2017, and has served since April 10, 2017.

Lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender (LGBT) persons in the U.S. state of Louisiana may face some legal challenges not experienced by non-LGBT residents. Same-sex sexual activity is legal in Louisiana as a result of the US Supreme Court decision in Lawrence v. Texas. Same-sex marriage has been recognized in the state since June 2015 as a result of the Supreme Court's decision in Obergefell v. Hodges.

Lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender (LGBT) rights in the U.S. state of Washington have evolved significantly since the late 20th century. Same-sex sexual activity was legalized in 1976. LGBT people are fully protected from discrimination in the areas of employment, housing and public accommodations; the state enacting comprehensive anti-discrimination legislation regarding sexual orientation and gender identity in 2006. Same-sex marriage has been legal since 2012, and same-sex couples are allowed to adopt. Conversion therapy on minors has also been illegal since 2018.

Lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender (LGBT) persons in the U.S. state of Arkansas may face some legal challenges not experienced by non-LGBT residents. Same-sex sexual activity is legal in Arkansas. Same-sex marriage became briefly legal through a court ruling on May 9, 2014, subject to court stays and appeals. In June 2015, the U.S. Supreme Court ruled in Obergefell v. Hodges that laws banning same-sex marriage are unconstitutional, legalizing same-sex marriage in the United States nationwide including in Arkansas. Nonetheless, discrimination on the basis of sexual orientation and gender identity was not banned in Arkansas until the Supreme Court banned it nationwide in Bostock v. Clayton County in 2020.

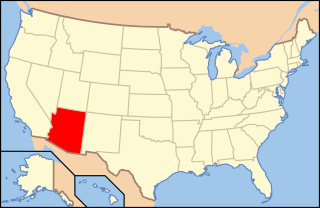

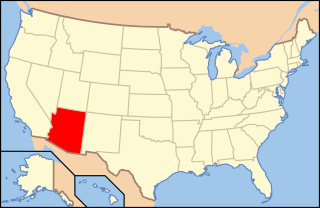

Lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender (LGBT) people in the U.S. state of Arizona may face legal challenges not experienced by non-LGBT residents. Same-sex sexual activity is legal in Arizona, and same-sex couples are able to marry and adopt. Nevertheless, the state provides only limited protections against discrimination on the basis of sexual orientation and gender identity. Several cities, including Phoenix and Tucson, have enacted ordinances to protect LGBT people from unfair discrimination in employment, housing and public accommodations.

Lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender (LGBT) people in the U.S. state of Indiana enjoy most of the same rights as non-LGBT people. Same-sex marriage has been legal in Indiana since October 6, 2014, when the U.S. Supreme Court refused to consider an appeal in the case of Baskin v. Bogan.

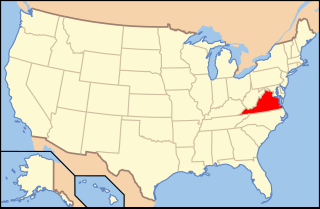

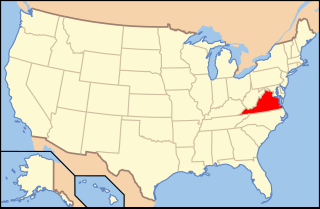

Lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender (LGBT) people in the Commonwealth of Virginia enjoy the same rights as non-LGBT persons. LGBT rights in the state are a recent occurrence with most improvements in LGBT rights occurring in the 2000s and 2010s. Same-sex marriage has been legal in Virginia since October 6, 2014, when the U.S. Supreme Court refused to consider an appeal in the case of Bostic v. Rainey. Effective July 1, 2020, there is a state-wide law protecting LGBT persons from discrimination in employment, housing, public accommodations, and credit. The state's hate crime laws also now explicitly include both sexual orientation and gender identity.

Lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender (LGBT) persons in the U.S. state of Nebraska may face some legal challenges not experienced by non-LGBT residents. Same-sex sexual activity is legal in Nebraska, and same-sex marriage has been recognized since June 2015 as a result of Obergefell v. Hodges. The state prohibits discrimination on account of sexual orientation and gender identity in employment and housing following the U.S. Supreme Court's ruling in Bostock v. Clayton County and a subsequent decision of the Nebraska Equal Opportunity Commission. In addition, the state's largest city, Omaha, has enacted protections in public accommodations.

Until 2017, laws related to LGBTQ+ couples adopting children varied by state. Some states granted full adoption rights to same-sex couples, while others banned same-sex adoption or only allowed one partner in a same-sex relationship to adopt the biological child of the other. Despite these rulings, same-sex couples and members of the LGBTQ+ community still face discrimination when attempting to foster children.

Obergefell v. Hodges, 576 U.S. 644 (2015), is a landmark decision of the Supreme Court of the United States which ruled that the fundamental right to marry is guaranteed to same-sex couples by both the Due Process Clause and the Equal Protection Clause of the Fourteenth Amendment of the Constitution. The 5–4 ruling requires all fifty states, the District of Columbia, and the Insular Areas to perform and recognize the marriages of same-sex couples on the same terms and conditions as the marriages of opposite-sex couples, with all the accompanying rights and responsibilities. Prior to Obergefell, same-sex marriage had already been established by statute, court ruling, or voter initiative in thirty-six states, the District of Columbia, and Guam.

Masterpiece Cakeshop v. Colorado Civil Rights Commission, 584 U.S. ___ (2018), was a case in the Supreme Court of the United States that dealt with whether owners of public accommodations can refuse certain services based on the First Amendment claims of free speech and free exercise of religion, and therefore be granted an exemption from laws ensuring non-discrimination in public accommodations—in particular, by refusing to provide creative services, such as making a custom wedding cake for the marriage of a gay couple, on the basis of the owner's religious beliefs.

In the United States, a religious freedom bill is a bill that, according to its proponents, allows those with religious objections to oppose LGBT rights in accordance with traditional religious teachings without being punished by the government for doing so. This typically concerns an employee who objects to abortion, euthanasia, same-sex marriage, civil unions, or transgender identity and wishes to avoid situations where they will be expected to put those objections aside. Proponents commonly refer to such proposals as religious liberty or conscience protection.

Amy Vivian Coney Barrett is an American lawyer and jurist who serves as an associate justice of the Supreme Court of the United States. The fifth woman to serve on the court, she was nominated by President Donald Trump and has served since October 27, 2020. Barrett was a U.S. circuit judge on the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Seventh Circuit from 2017 to 2020.

Our Lady of Guadalupe School v. Morrissey-Berru, 591 U.S. ___ (2020), was a United States Supreme Court case involving the ministerial exception of federal employment discrimination laws. The case extends from the Supreme Court's prior decision in Hosanna-Tabor Evangelical Lutheran Church & School v. Equal Employment Opportunity Commission which created the ministerial exception based on the Establishment and Free Exercise Clauses of the United States Constitution, asserting that federal discrimination laws cannot be applied to leaders of religious organizations. The case, along with the consolidated St. James School v. Biel, both arose from rulings in the United States Court of Appeals for the Ninth Circuit that found that federal discrimination laws do apply to others within a religious organization that serve an important religious function but lack the title or training to be considered a religious leader under Hosanna-Tabor. The religious organization challenged that ruling on the basis of Hosanna-Tabor. The Supreme Court ruled in a 7–2 decision on July 8, 2020 that reversed the Ninth Circuit's ruling, affirming that the principles of Hosanna-Tabor, that a person can be serving an important religious function even if not holding the title or training of a religious leader, satisfied the ministerial exception in employment discrimination.

303 Creative LLC v. Elenis, 600 U.S. 570 (2023), is a United States Supreme Court decision that dealt with the intersection of anti-discrimination law in public accommodations with the Free Speech Clause of the First Amendment to the United States Constitution. In a 6–3 decision, the Court found for a website designer, ruling that the state of Colorado cannot compel the designer to create work that violates her values. The case follows from Masterpiece Cakeshop v. Colorado Civil Rights Commission, 584 U.S. ___ (2018), which had dealt with similar conflict between free speech rights and Colorado's anti-discrimination laws, but was decided on narrower grounds.