The Religious Freedom Restoration Act of 1993, Pub. L. No. 103-141, 107 Stat. 1488, codified at 42 U.S.C. § 2000bb through 42 U.S.C. § 2000bb-4, is a 1993 United States federal law that "ensures that interests in religious freedom are protected." The bill was introduced by Congressman Chuck Schumer (D-NY) on March 11, 1993. A companion bill was introduced in the Senate by Ted Kennedy (D-MA) the same day. A unanimous U.S. House and a nearly unanimous U.S. Senate—three senators voted against passage—passed the bill, and President Bill Clinton signed it into law.

The Little Sisters of the Poor is a Catholic religious institute for women. It was founded by Jeanne Jugan. Having felt the need to care for the many impoverished elderly who lined the streets of French towns and cities, Jugan established the congregation to care for the elderly in 1839.

Priests for Life (PFL) is an anti-abortion organization based in Titusville, Florida. PFL functions as a network to promote and coordinate anti-abortion activism, especially among Roman Catholic priests and laymen, with the primary strategic goal of ending abortion and euthanasia and to spread the message of the Evangelium vitae encyclical, written by Pope John Paul II.

Becket Law, formerly the Becket Fund for Religious Liberty, is a non-profit public interest law firm based in Washington, D.C., that describes its mission as "defending the freedom of religion of people of all faiths". Becket promotes accommodationism and is active in the judicial system, the media, and in education.

Conestoga Wood Specialties is a manufacturer of wood doors and components for kitchen, bath and furniture, based in East Earl, Pennsylvania. They have five factories, located in Washington, North Carolina, and Pennsylvania, employing about 1,200 people.

Scott Milne Matheson Jr. is a United States circuit judge of the United States Court of Appeals for the Tenth Circuit. He has served on that court since 2010.

Jerry Edwin Smith is an American attorney and jurist serving as a United States circuit judge of the United States Court of Appeals for the Fifth Circuit.

This is a timeline of reproductive rights legislation, a chronological list of laws and legal decisions affecting human reproductive rights. Reproductive rights are a sub-set of human rights pertaining to issues of reproduction and reproductive health. These rights may include some or all of the following: the right to legal or safe abortion, the right to birth control, the right to access quality reproductive healthcare, and the right to education and access in order to make reproductive choices free from coercion, discrimination, and violence. Reproductive rights may also include the right to receive education about contraception and sexually transmitted infections, and freedom from coerced sterilization, abortion, and contraception, and protection from practices such as female genital mutilation (FGM).

The birth control movement in the United States was a social reform campaign beginning in 1914 that aimed to increase the availability of contraception in the U.S. through education and legalization. The movement began in 1914 when a group of political radicals in New York City, led by Emma Goldman, Mary Dennett, and Margaret Sanger, became concerned about the hardships that childbirth and self-induced abortions brought to low-income women. Since contraception was considered to be obscene at the time, the activists targeted the Comstock laws, which prohibited distribution of any "obscene, lewd, and/or lascivious" materials through the mail. Hoping to provoke a favorable legal decision, Sanger deliberately broke the law by distributing The Woman Rebel, a newsletter containing a discussion of contraception. In 1916, Sanger opened the first birth control clinic in the United States, but the clinic was immediately shut down by police, and Sanger was sentenced to 30 days in jail.

Birth control in the United States is available in many forms. Some of the forms available at drugstores and some retail stores are male condoms, female condoms, sponges, spermicides, and over-the-counter emergency contraception. Forms available at pharmacies with a doctor's prescription or at doctor's offices are oral contraceptive pills, patches, vaginal rings, diaphragms, shots/injections, cervical caps, implantable rods, and intrauterine devices (IUDs). Sterilization procedures, including tubal ligations and vasectomies, are also performed.

A contraceptive mandate is a government regulation or law that requires health insurers, or employers that provide their employees with health insurance, to cover some contraceptive costs in their health insurance plans.

Since the passage of the Affordable Care Act (ACA), there have been numerous actions in federal courts to challenge the constitutionality of the legislation. They include challenges by states against the ACA, reactions from legal experts with respect to its constitutionality, several federal court rulings on the ACA's constitutionality, the final ruling on the constitutionality of the legislation by the U.S. Supreme Court in National Federation of Independent Business v. Sebelius, and notable subsequent lawsuits challenging the ACA. The Supreme Court upheld ACA for a third time in a June 2021 decision.

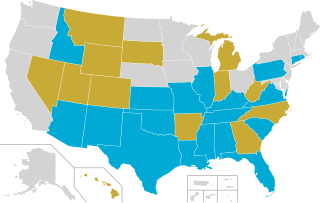

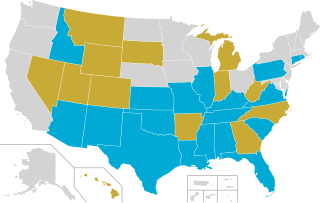

State Religious Freedom Restoration Acts are state laws based on the Religious Freedom Restoration Act (RFRA), a federal law that was passed almost unanimously by the U.S. Congress in 1993 and signed into law by President Bill Clinton. The laws mandate that religious liberty of individuals can only be limited by the "least restrictive means of furthering a compelling government interest". Originally, the federal law was intended to apply to federal, state, and local governments. In 1997, the U.S. Supreme Court in City of Boerne v. Flores held that the Religious Freedom Restoration Act only applies to the federal government but not states and other local municipalities within them. As a result, 21 states have passed their own RFRAs that apply to their individual state and local governments.

Burwell v. Hobby Lobby Stores, Inc., 573 U.S. 682 (2014), is a landmark decision in United States corporate law by the United States Supreme Court allowing privately held for-profit corporations to be exempt from a regulation that its owners religiously object to, if there is a less restrictive means of furthering the law's interest, according to the provisions of the Religious Freedom Restoration Act of 1993. It is the first time that the Court has recognized a for-profit corporation's claim of religious belief, but it is limited to privately held corporations. The decision does not address whether such corporations are protected by the free exercise of religion clause of the First Amendment of the Constitution.

King v. Burwell, 576 U.S. 473 (2015), was a 6–3 decision by the Supreme Court of the United States interpreting provisions of the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act (ACA). The Court's decision upheld, as consistent with the statute, the outlay of premium tax credits to qualifying persons in all states, both those with exchanges established directly by a state, and those otherwise established by the Department of Health and Human Services.

Paul Joseph Wieland is an American businessman and politician from the state of Missouri. A member of the Republican Party, Wieland represents the 22nd District in the Missouri State Senate.

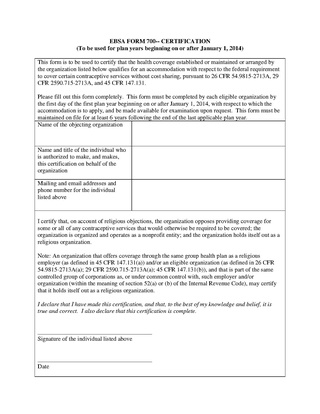

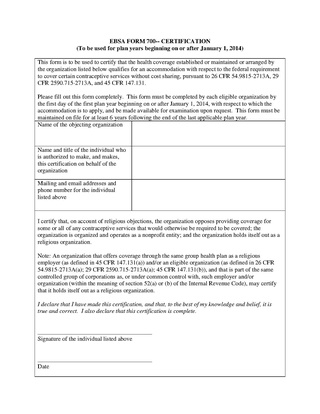

EBSA Form 700 is a form that the United States Government had required certain non-profit organizations to complete and submit, beginning January 1, 2014, in order to claim an exemption from the contraceptive mandate under the Affordable Care Act. After the U.S. Supreme court issued temporary injunctions, preventing any penalty against some non-profit institutions who objected to filing the form, the U.S. Department of Labor issued a new version of the form making it clear that organizations can, instead object by a letter.

California v. Texas, 593 U.S. ___ (2021), was a United States Supreme Court case that dealt with the constitutionality of the 2010 Affordable Care Act (ACA), colloquially known as Obamacare. It was the third such challenge to the ACA seen by the Supreme Court since its enactment. The case in California followed after the enactment of the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act of 2017 and the change to the tax penalty amount for Americans without required insurance that reduced the "individual mandate" to zero, effective for months after December 31, 2018. The District Court of the Northern District of Texas concluded that this individual mandate was a critical provision of the ACA and that, with a penalty amount equal to zero, some or all of the ACA was potentially unconstitutional as an improper use of Congress's taxation powers.

Little Sisters of the Poor Saints Peter and Paul Home v. Pennsylvania, 591 U.S. ___ (2020), was a United States Supreme Court case involving ongoing conflicts between the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act (ACA) and the Religious Freedom Restoration Act (RFRA) over the ACA's contraceptive mandate. The ACA exempts nonprofit religious organizations from complying with the mandate, to which for-profit religious organizations objected.