The First Amendment to the United States Constitution prevents the government from making laws respecting an establishment of religion; prohibiting the free exercise of religion; or abridging the freedom of speech, the freedom of the press, the freedom of assembly, or the right to petition the government for redress of grievances. It was adopted on December 15, 1791, as one of the ten amendments that constitute the Bill of Rights.

Clear and present danger was a doctrine adopted by the Supreme Court of the United States to determine under what circumstances limits can be placed on First Amendment freedoms of speech, press, or assembly. Created by Justice Oliver Wendell Holmes Jr. to refine the bad tendency test, it was never fully adopted and both tests were ultimately replaced in 1969 with Brandenburg v. Ohio's "imminent lawless action" test.

Dennis v. United States, 341 U.S. 494 (1951), was a United States Supreme Court case relating to Eugene Dennis, General Secretary of the Communist Party USA. The Court ruled that Dennis did not have the right under the First Amendment to the United States Constitution to exercise free speech, publication and assembly, if the exercise involved the creation of a plot to overthrow the government. In 1969, Dennis was de facto overruled by Brandenburg v. Ohio.

New York Times Co. v. United States, 403 U.S. 713 (1971), was a landmark decision of the Supreme Court of the United States on the First Amendment right to freedom of the press. The ruling made it possible for The New York Times and The Washington Post newspapers to publish the then-classified Pentagon Papers without risk of government censorship or punishment.

Brandenburg v. Ohio, 395 U.S. 444 (1969), is a landmark decision of the United States Supreme Court interpreting the First Amendment to the U.S. Constitution. The Court held that the government cannot punish inflammatory speech unless that speech is "directed to inciting or producing imminent lawless action and is likely to incite or produce such action". Specifically, the Court struck down Ohio's criminal syndicalism statute, because that statute broadly prohibited the mere advocacy of violence. In the process, Whitney v. California (1927) was explicitly overruled, and Schenck v. United States (1919), Abrams v. United States (1919), Gitlow v. New York (1925), and Dennis v. United States (1951) were overturned.

Whitney v. California, 274 U.S. 357 (1927), was a United States Supreme Court decision upholding the conviction of an individual who had engaged in speech that raised a clear and present danger to society. While the majority of the Supreme Court Justices voted to uphold the conviction, the ruling has become an important free speech precedent due a concurring opinion by Justice Louis Brandeis recommending new perspectives on criticism of the government by citizens. The ruling was explicitly overruled by Brandenburg v. Ohio in 1969.

Gitlow v. New York, 268 U.S. 652 (1925), was a landmark decision of the United States Supreme Court holding that the Fourteenth Amendment to the United States Constitution had extended the First Amendment's provisions protecting freedom of speech and freedom of the press to apply to the governments of U.S. states. Along with Chicago, Burlington & Quincy Railroad Co. v. City of Chicago (1897), it was one of the first major cases involving the incorporation of the Bill of Rights. It was also one of a series of Supreme Court cases that defined the scope of the First Amendment's protection of free speech and established the standard to which a state or the federal government would be held when it criminalized speech or writing.

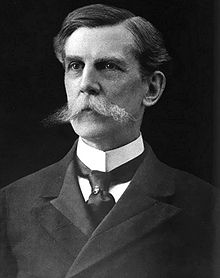

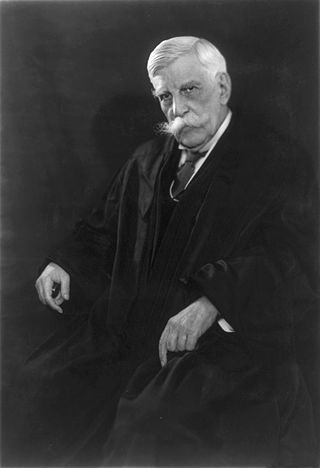

Oliver Wendell Holmes Jr. was an American jurist who served as an associate justice of the U.S. Supreme Court from 1902 to 1932. Holmes is one of the most widely cited Supreme Court justices and among the most influential American judges in history, noted for his long service, pithy opinions—particularly those on civil liberties and American constitutional democracy—and deference to the decisions of elected legislatures. Holmes retired from the court at the age of 90, an unbeaten record for oldest justice on the Supreme Court. He previously served as a Brevet Colonel in the American Civil War, in which he was wounded three times, as an associate justice and chief justice of the Massachusetts Supreme Judicial Court, and as Weld Professor of Law at his alma mater, Harvard Law School. His positions, distinctive personality, and writing style made him a popular figure, especially with American progressives.

Abrams v. United States, 250 U.S. 616 (1919), was a decision by the Supreme Court of the United States upholding the criminal arrests of several defendants under the Sedition Act of 1918, which was an amendment to the Espionage Act of 1917. The law made it a criminal offense to criticize the production of war materiel with intent to hinder the progress of American military efforts.

"Shouting fire in a crowded theater" is a popular analogy for speech or actions whose principal purpose is to create panic, and in particular for speech or actions which may for that reason be thought to be outside the scope of free speech protections. The phrase is a paraphrasing of a dictum, or non-binding statement, from Justice Oliver Wendell Holmes Jr.'s opinion in the United States Supreme Court case Schenck v. United States in 1919, which held that the defendant's speech in opposition to the draft during World War I was not protected free speech under the First Amendment of the United States Constitution. The case was later partially overturned by Brandenburg v. Ohio in 1969, which limited the scope of banned speech to that which would be directed to and likely to incite imminent lawless action.

Stromberg v. California, 283 U.S. 359 (1931), was a landmark decision of the Supreme Court of the United States in which the Court held, 7–2, that a California statute banning red flags was unconstitutional because it violated the First and Fourteenth Amendments to the United States Constitution. In the case, Yetta Stromberg was convicted for displaying a red flag daily in the youth camp for children at which she worked, and was charged in accordance with California law. Chief Justice Charles Hughes wrote for the seven-justice majority that the California statute was unconstitutional, and therefore Stromberg's conviction could not stand.

Feiner v. New York, 340 U.S. 315 (1951), was a United States Supreme Court case involving Irving Feiner's arrest for a violation of section 722 of the New York Penal Code, "inciting a breach of the peace," as he addressed a crowd on a street.

Zechariah Chafee Jr. was an American judicial philosopher and civil rights advocate, described as "possibly the most important First Amendment scholar of the first half of the twentieth century" by Richard Primus. Chafee's avid defense of freedom of speech led to Senator Joseph McCarthy calling him "dangerous" to America.

In United States law, the bad tendency principle was a test that permitted restriction of freedom of speech by government if it is believed that a form of speech has a sole tendency to incite or cause illegal activity. The principle, formulated in Patterson v. Colorado (1907), was seemingly overturned with the "clear and present danger" principle used in the landmark case Schenck v. United States (1919), as stated by Justice Oliver Wendell Holmes Jr. Yet eight months later, at the start of the next term in Abrams v. United States (1919), the Court again used the bad tendency test to uphold the conviction of a Russian immigrant who published and distributed leaflets calling for a general strike and otherwise advocated revolutionary, anarchist, and socialist views. Holmes dissented in Abrams, explaining how the clear and present danger test should be employed to overturn Abrams' conviction. The re-emergence of the bad tendency test resulted in a string of cases after Abrams employing that test, including Whitney v. California (1927), where a woman was convicted simply because of her association with the Communist Party. The court ruled unanimously that although she had not committed any crimes, her relationship with the Communists represented a "bad tendency" and thus was unprotected. The "bad tendency" test was finally overturned in Brandenburg v. Ohio (1969) and was replaced by the "imminent lawless action" test.

Terminiello v. City of Chicago, 337 U.S. 1 (1949), was a case in which the Supreme Court of the United States held that a "breach of peace" ordinance of the City of Chicago that banned speech that "stirs the public to anger, invites dispute, brings about a condition of unrest, or creates a disturbance" was unconstitutional under the First and Fourteenth Amendments to the United States Constitution.

Kunz v. New York, 340 U.S. 290 (1951), was a United States Supreme Court case finding a requirement mandating a permit to speak on religious issues in public was unconstitutional. It was argued October 17, 1950, and decided January 15, 1951, 8–1. Chief Justice Vinson delivered the opinion for the Court. Justice Black and Justice Frankfurter concurred in the result only. Justice Jackson dissented.

The Smith Act trials of Communist Party leaders took place in New York City from 1949 to 1958. These trials were a series of prosecutions carried out by the US federal government during the postwar period and the Cold War era, which was characterized by tensions between the United States and the Soviet Union. The leaders of the Communist Party of the United States (CPUSA) faced accusations of violating the Smith Act, a statute that made it illegal to advocate for the violent overthrow of the government. In their defense, the defendants claimed that they advocated for a peaceful transition to socialism and that their membership in a political party was protected by the First Amendment's guarantees of freedom of speech and association. The issues raised in these trials were eventually addressed by the US Supreme Court in its rulings Dennis v. United States (1951) and Yates v. United States (1957).

Frohwerk v. United States, 249 U.S. 204 (1919), was a United States Supreme Court case in which the Court upheld the conviction of a newspaperman for violating the Espionage Act of 1917 in connection with criticism of U.S. involvement in foreign wars.

Freedom for the Thought That We Hate: A Biography of the First Amendment is a 2007 non-fiction book by journalist Anthony Lewis about freedom of speech, freedom of the press, freedom of thought, and the First Amendment to the United States Constitution. The book starts by quoting the First Amendment, which prohibits the U.S. Congress from creating legislation which limits free speech or freedom of the press. Lewis traces the evolution of civil liberties in the U.S. through key historical events. He provides an overview of important free speech case law, including U.S. Supreme Court opinions in Schenck v. United States (1919), Whitney v. California (1927), United States v. Schwimmer (1929), New York Times Co. v. Sullivan (1964), and New York Times Co. v. United States (1971).

The White Court refers to the Supreme Court of the United States from 1910 to 1921, when Edward Douglass White served as Chief Justice of the United States. White, an associate justice since 1894, succeeded Melville Fuller as Chief Justice after the latter's death, and White served as Chief Justice until his death a decade later. He was the first sitting associate justice to be elevated to chief justice in the Court's history. He was succeeded by former president William Howard Taft.