The Andes, Andes Mountains or Andean Mountain Range are the longest continental mountain range in the world, forming a continuous highland along the western edge of South America. The range is 8,900 km (5,530 mi) long, 200 to 700 km wide, and has an average height of about 4,000 m (13,123 ft). The Andes extend from north to south through seven South American countries: Venezuela, Colombia, Ecuador, Peru, Bolivia, Chile and Argentina.

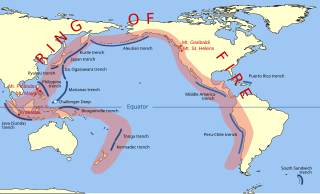

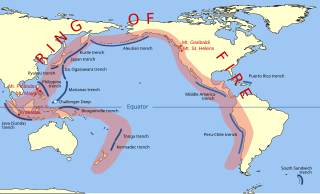

The Ring of Fire is a region around much of the rim of the Pacific Ocean where many volcanic eruptions and earthquakes occur. The Ring of Fire is a horseshoe-shaped belt about 40,000 km (25,000 mi) long and up to about 500 km (310 mi) wide.

The Nazca Plate or Nasca Plate, named after the Nazca region of southern Peru, is an oceanic tectonic plate in the eastern Pacific Ocean basin off the west coast of South America. The ongoing subduction, along the Peru–Chile Trench, of the Nazca Plate under the South American Plate is largely responsible for the Andean orogeny. The Nazca Plate is bounded on the west by the Pacific Plate and to the south by the Antarctic Plate through the East Pacific Rise and the Chile Rise respectively. The movement of the Nazca Plate over several hotspots has created some volcanic islands as well as east–west running seamount chains that subduct under South America. Nazca is a relatively young plate both in terms of the age of its rocks and its existence as an independent plate having been formed from the break-up of the Farallon Plate about 23 million years ago. The oldest rocks of the plate are about 50 million years old.

The Antarctic Plate is a tectonic plate containing the continent of Antarctica, the Kerguelen Plateau, and some remote islands in the Southern Ocean and other surrounding oceans. After breakup from Gondwana, the Antarctic plate began moving the continent of Antarctica south to its present isolated location, causing the continent to develop a much colder climate. The Antarctic Plate is bounded almost entirely by extensional mid-ocean ridge systems. The adjoining plates are the Nazca Plate, the South American Plate, the African Plate, the Somali Plate, the Indo-Australian Plate, the Pacific Plate, and, across a transform boundary, the Scotia Plate.

Nevado Ojos del Salado is a dormant complex volcano in the Andes on the Argentina–Chile border. It is the highest volcano on Earth and the highest peak in Chile. The upper reaches of Ojos del Salado consist of several overlapping lava domes, lava flows and volcanic craters, with an only sparse ice cover. The complex extends over an area of 70–160 square kilometres (27–62 sq mi) and its highest summit reaches an altitude of 6,893 metres (22,615 ft) above sea level. Numerous other volcanoes rise around Ojos del Salado.

Viedma is a subglacial volcano whose existence is questionable. It is supposedly located below the ice of the Southern Patagonian Ice Field, an area disputed between Argentina and Chile. The 1988 eruption deposited ash and pumice on the ice field and produced a mudflow that reached Viedma Lake. The exact position of the edifice is unclear, both owing to the ice cover and because the candidate position, the "Viedma Nunatak", does not clearly appear to be of volcanic nature.

Mentolat is an ice-filled, 6 km (4 mi) wide caldera in the central portion of Magdalena Island, Aisén Province, Chilean Patagonia. This caldera sits on top of a stratovolcano which has generated lava flows and pyroclastic flows. The caldera is filled with a glacier.

Cerro Macá is a stratovolcano located to the north of the Aisén Fjord and to the east of the Moraleda Channel, in the Aysén del General Carlos Ibáñez del Campo Region of Chile. This glacier-covered volcano lies along the regional Liquiñe-Ofqui Fault Zone.

The geology of the Pacific Northwest includes the composition, structure, physical properties and the processes that shape the Pacific Northwest region of North America. The region is part of the Ring of Fire: the subduction of the Pacific and Farallon Plates under the North American Plate is responsible for many of the area's scenic features as well as some of its hazards, such as volcanoes, earthquakes, and landslides.

Because Chile extends from a point about 625 kilometers north of the Tropic of Capricorn to a point hardly more than 1,400 kilometers north of the Antarctic Circle, within its territory can be found a broad selection of the Earth's climates.

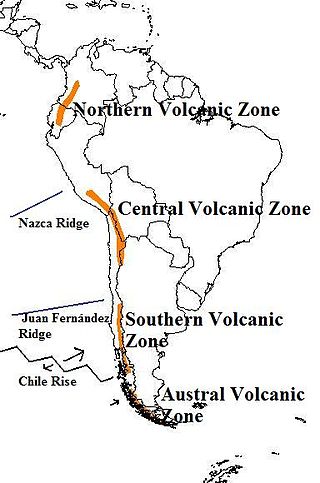

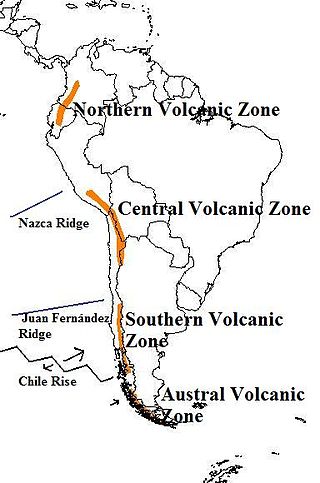

The Andean Volcanic Belt is a major volcanic belt along the Andean cordillera in Argentina, Bolivia, Chile, Colombia, Ecuador, and Peru. It is formed as a result of subduction of the Nazca Plate and Antarctic Plate underneath the South American Plate. The belt is subdivided into four main volcanic zones which are separated by volcanic gaps. The volcanoes of the belt are diverse in terms of activity style, products, and morphology. While some differences can be explained by which volcanic zone a volcano belongs to, there are significant differences within volcanic zones and even between neighboring volcanoes. Despite being a type location for calc-alkalic and subduction volcanism, the Andean Volcanic Belt has a broad range of volcano-tectonic settings, as it has rift systems and extensional zones, transpressional faults, subduction of mid-ocean ridges and seamount chains as well as a large range of crustal thicknesses and magma ascent paths and different amounts of crustal assimilations.

The Chile Triple Junction is a geologic triple junction located on the seafloor of the Pacific Ocean off Taitao and Tres Montes Peninsula on the southern coast of Chile. Here three tectonic plates meet: the South American Plate, the Nazca Plate and the Antarctic Plate. This triple junction is unusual in that it consists of a mid-oceanic ridge, the Chile Rise, being subducted under the South American Plate at the Peru–Chile Trench. The Chile Triple Junction is the boundary between the Chilean Rise and the Chilean margin, where the Nazca, Antarctic, and South American plates meet at the trench.

The Nazca Ridge is a submarine ridge, located on the Nazca Plate off the west coast of South America. This plate and ridge are currently subducting under the South American Plate at a convergent boundary known as the Peru-Chile Trench at approximately 7.7 cm (3.0 in) per year. The Nazca Ridge began subducting obliquely to the collision margin at 11°S, approximately 11.2 Ma, and the current subduction location is 15°S. The ridge is composed of abnormally thick basaltic ocean crust, averaging 18 ±3 km thick. This crust is buoyant, resulting in flat slab subduction under Peru. This flat slab subduction has been associated with the uplift of Pisco Basin and the cessation of Andes volcanism and the uplift of the Fitzcarrald Arch on the South American continent approximately 4 Ma.

The Andean orogeny is an ongoing process of orogeny that began in the Early Jurassic and is responsible for the rise of the Andes mountains. The orogeny is driven by a reactivation of a long-lived subduction system along the western margin of South America. On a continental scale the Cretaceous and Oligocene were periods of re-arrangements in the orogeny. The details of the orogeny vary depending on the segment and the geological period considered.

Aguas Calientes is a major Miocene caldera in Salta Province, Argentina. It is in the Central Volcanic Zone of the Andes, a zone of volcanism covering southern Peru, Bolivia, northwest Argentina and northern Chile. This zone contains stratovolcanoes and calderas.

Jotabeche is a Miocene-Pliocene caldera in the Atacama Region of Chile. It is part of the volcanic Andes, more specifically of the extreme southern end of the Central Volcanic Zone (CVZ). This sector of the Andean Volcanic Belt contains about 44 volcanic centres and numerous more minor volcanic systems, as well as some caldera and ignimbrite systems. Jotabeche is located in a now inactive segment of the CVZ, the Maricunga Belt.

Fueguino is a volcanic field in Chile. The southernmost volcano in the Andes, it lies on Tierra del Fuego's Cook Island and also extends over nearby Londonderry Island. The field is formed by lava domes, pyroclastic cones, and a crater lake.

Wheelwright caldera is a caldera in Chile. It is variously described as being between 11 kilometres (6.8 mi) and 22 kilometres (14 mi) wide and lies in the Central Volcanic Zone of the Andes. A lake lies within the caldera, which is among the largest of the Central Andes. The caldera lies in the region of Ojos del Salado, the world's tallest volcano.

Sillajhuay is a volcano on the border between Bolivia and Chile. It is part of a volcanic chain that stretches across the border between Bolivia and Chile and forms a mountain massif that is in part covered by ice; whether this ice should be considered a glacier is debatable but it has been retreating in recent decades.

The Chile Ridge, also known as the Chile Rise, is a submarine oceanic ridge formed by the divergent plate boundary between the Nazca Plate and the Antarctic Plate. It extends from the triple junction of the Nazca, Pacific, and Antarctic plates to the Southern coast of Chile. The Chile Ridge is easy to recognize on the map, as the ridge is divided into several segmented fracture zones which are perpendicular to the ridge segments, showing an orthogonal shape toward the spreading direction. The total length of the ridge segments is about 550–600 km.