Related Research Articles

In morphology and syntax, a clitic is a morpheme that has syntactic characteristics of a word, but depends phonologically on another word or phrase. In this sense, it is syntactically independent but phonologically dependent—always attached to a host. A clitic is pronounced like an affix, but plays a syntactic role at the phrase level. In other words, clitics have the form of affixes, but the distribution of function words.

In language, a clause is a constituent that comprises a semantic predicand and a semantic predicate. A typical clause consists of a subject and a syntactic predicate, the latter typically a verb phrase composed of a verb with any objects and other modifiers. However, the subject is sometimes unvoiced if it is retrievable from context, especially in null-subject language but also in other languages, including English instances of the imperative mood.

Fijian is an Austronesian language of the Malayo-Polynesian family spoken by some 350,000–450,000 ethnic Fijians as a native language. The 2013 Constitution established Fijian as an official language of Fiji, along with English and Fiji Hindi and there is discussion about establishing it as the "national language". Fijian is a VOS language.

A subject is one of the two main parts of a sentence.

Mbula is an Austronesian language spoken by around 2,500 people on Umboi Island and Sakar Island in the Morobe Province of Papua New Guinea. Its basic word order is subject–verb–object; it has a nominative–accusative case-marking strategy.

In linguistics, especially within generative grammar, phi features are the morphological expression of a semantic process in which a word or morpheme varies with the form of another word or phrase in the same sentence. This variation can include person, number, gender, and case, as encoded in pronominal agreement with nouns and pronouns. Several other features are included in the set of phi-features, such as the categorical features ±N (nominal) and ±V (verbal), which can be used to describe lexical categories and case features.

In linguistics, raising constructions involve the movement of an argument from an embedded or subordinate clause to a matrix or main clause. In other words, a raising predicate/verb appears with a syntactic argument that is not its semantic argument but rather the semantic argument of an embedded predicate. For example, in they seem to be trying, the predicand of trying is the subject of seem. English has raising constructions, unlike some other languages.

Personal pronouns are pronouns that are associated primarily with a particular grammatical person – first person, second person, or third person. Personal pronouns may also take different forms depending on number, grammatical or natural gender, case, and formality. The term "personal" is used here purely to signify the grammatical sense; personal pronouns are not limited to people and can also refer to animals and objects.

Hindustani, the lingua franca of Northern India and Pakistan, has two standardised registers: Hindi and Urdu. Grammatical differences between the two standards are minor but each uses its own script: Hindi uses Devanagari while Urdu uses an extended form of the Perso-Arabic script, typically in the Nastaʿlīq style.

In linguistics, volition is a concept that distinguishes whether the subject, or agent of a particular sentence intended an action or not. Simply, it is the intentional or unintentional nature of an action. Volition concerns the idea of control and for the purposes outside of psychology and cognitive science, is considered the same as intention in linguistics. Volition can then be expressed in a given language using a variety of possible methods. These sentence forms usually indicate that a given action has been done intentionally, or willingly. There are various ways of marking volition cross-linguistically. When using verbs of volition in English, like "want" or "prefer", these verbs are not expressly marked. Other languages handle this with affixes, while others have complex structural consequences of volitional or non-volitional encoding.

Exceptional case-marking (ECM), in linguistics, is a phenomenon in which the subject of an embedded infinitival verb seems to appear in a superordinate clause and, if it is a pronoun, is unexpectedly marked with object case morphology. The unexpected object case morphology is deemed "exceptional". The term ECM itself was coined in the Government and Binding grammar framework although the phenomenon is closely related to the accusativus cum infinitivo constructions of Latin. ECM-constructions are also studied within the context of raising. The verbs that license ECM are known as raising-to-object verbs. Many languages lack ECM-predicates, and even in English, the number of ECM-verbs is small. The structural analysis of ECM-constructions varies in part according to whether one pursues a relatively flat structure or a more layered one.

Wagiman, also spelt Wageman, Wakiman, Wogeman, and other variants, is a near-extinct Aboriginal Australian language spoken by a small number of Wagiman people in and around Pine Creek, in the Katherine Region of the Northern Territory.

The Nias language is an Austronesian language spoken on Nias Island and the Batu Islands off the west coast of Sumatra in Indonesia. It is known as Li Niha by its native speakers. It belongs to the Northwest Sumatra–Barrier Islands subgroup which also includes Mentawai and the Batak languages. It had about 770,000 speakers in 2000. There are three main dialects: northern, central and southern. It is an open-syllable language, which means there are no syllable-final consonants.

The Ngarnji (Ngarndji) or Ngarnka language was traditionally spoken by the Ngarnka people of the Barkly Tablelands in the Northern Territory of Australia. The last fluent speaker of the language died between 1997 and 1998. Ngarnka belongs to the Mirndi language family, in the Ngurlun branch. It is closely related to its eastern neighbours Binbinka, Gudanji and Wambaya. It is more distantly related to its western neighbour Jingulu, and three languages of the Victoria River District, Jaminjung, Ngaliwurru and Nungali. There is very little documentation and description of Ngarnka, however there have been several graduate and undergraduate dissertations written on various aspects of Ngarnka morphology, and a sketch grammar and lexicon of Ngarnka is currently in preparation.

Ramarama, also known as Karo, is a Tupian language of Brazil.

Mekeo is a language spoken in Papua New Guinea and had 19,000 speakers in 2003. It is an Oceanic language of the Papuan Tip Linkage. The two major villages that the language is spoken in are located in the Central Province of Papua New Guinea. These are named Ongofoina and Inauaisa. The language is also broken up into four dialects: East Mekeo; North West Mekeo; West Mekeo and North Mekeo. The standard dialect is East Mekeo. This main dialect is addressed throughout the article. In addition, there are at least two Mekeo-based pidgins.

Djaru (Tjaru) is a Pama–Nyungan language spoken in the south-eastern Kimberley region of Western Australia. As with most Pama-Nyungan languages, Djaru includes single, dual and plural pronoun numbers. Djaru also includes sign-language elements in its lexicon. Nouns in Djaru do not include gender classes, and apart from inflections, words are formed through roots, compounding or reduplication. Word order in Djaru is relatively free and has the ability to split up noun phrases. The Djaru language has a relatively small number of verbs, as compared to most languages, and thus utilizes a system of 'preverbs' and complex verbs to compensate. Djaru also has an avoidance language. Avoidance languages, sometimes known as 'mother-in-law languages', are special registers within a language that are spoken between certain family members – such registers are common throughout native Australian languages.

This article describes the syntax of clauses in the English language, chiefly in Modern English. A clause is often said to be the smallest grammatical unit that can express a complete proposition. But this semantic idea of a clause leaves out much of English clause syntax. For example, clauses can be questions, but questions are not propositions. A syntactic description of an English clause is that it is a subject and a verb. But this too fails, as a clause need not have a subject, as with the imperative, and, in many theories, an English clause may be verbless. The idea of what qualifies varies between theories and has changed over time.

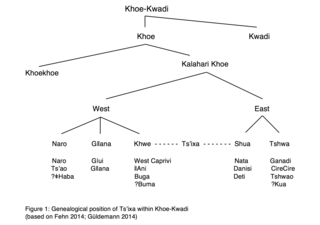

Tsʼixa is a critically endangered African language that belongs to the Kalahari Khoe branch of the Khoe-Kwadi language family. The Tsʼixa speech community consists of approximately 200 speakers who live in Botswana on the eastern edge of the Okavango Delta, in the small village of Mababe. They are a foraging society that consists of the ethnically diverse groups commonly subsumed under the names "San", "Bushmen" or "Basarwa". The most common term of self-reference within the community is Xuukhoe or 'people left behind', a rather broad ethnonym roughly equaling San, which is also used by Khwe-speakers in Botswana. Although the affiliation of Tsʼixa within the Khalari Khoe branch, as well as the genetic classification of the Khoisan languages in general, is still unclear, the Khoisan language scholar Tom Güldemann posits in a 2014 article the following genealogical relationships within Khoe-Kwadi, and argues for the status of Tsʼixa as a language in its own right. The language tree to the right presents a possible classification of Tsʼixa within Khoe-Kwadi:

Hindustani verbs conjugate according to mood, tense, person and number. Hindustani inflection is markedly simpler in comparison to Sanskrit, from which Hindustani has inherited its verbal conjugation system. Aspect-marking participles in Hindustani mark the aspect. Gender is not distinct in the present tense of the indicative mood, but all the participle forms agree with the gender and number of the subject. Verbs agree with the gender of the subject or the object depending on whether the subject pronoun is in the dative or ergative case or the nominative case.

References

- Adger, D. 2003. Core syntax: A minimalist approach. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press.

- Butt, M. 2003. The Light Verb Jungle. In Harvard Working Papers in Linguistics, ed. G. Aygen, C. Bowern, and C. Quinn. 1–49. Volume 9, Papers from the GSAS/Dudley House workshop on light verbs.

- Collins Cobuild English Grammar 1995. London: HarperCollins Publishers.

- Grimshaw, J. and A. Mester. 1988. Light verbs and ɵ-Marking. Linguistic Inquiry 19, 205–232.

- Hornstein, N., J. Nunes, and K. Grohmann 2005. Understanding Minimalism. New York: Cambridge University Press.

- Jespersen, O. 1965. A Modern English Grammar on Historical Principles, Part VI, Morphology. London: George Allen and Unwin Ltd.

- Osborne, T. and T. Groß 2012. Constructions are catenae: Construction Grammar meets Dependency Grammar. Cognitive Linguistics 23, 1, 163–214.

- Schmidt, Hans (2003). "Temathesis in Rotuman" (PDF). In John Lynch (ed.). Issues in Austronesian Historical Phonology. Pacific Linguistics Research School of Pacific and Asian Studies. pp. 175–207. ISBN 978-0-85883-503-0.

- Shapiro, Michael C. (2003). "Hindi". In Cardona, George; Jain, Dhanesh (eds.). The Indo-Aryan Languages. Routledge. pp. 250–285. ISBN 978-0-415-77294-5.

- Snell, Rupert; Weightman, Simon (1989). Teach Yourself Hindi (2003 ed.). McGraw-Hill. ISBN 978-0-07-142012-9.

- Steven, S., A. Fazly, and R.North. 2004. Statistical measures of the semi-productivity of light verb constructions. In 2nd ACL workshop on multiword expressions: Integrating processing, pp. 1–8.