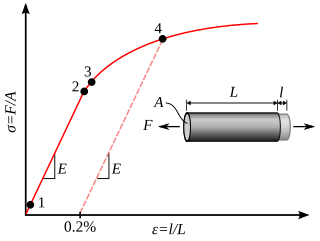

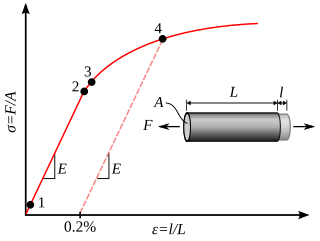

In engineering, deformation refers to the change in size or shape of an object. Displacements are the absolute change in position of a point on the object. Deflection is the relative change in external displacements on an object. Strain is the relative internal change in shape of an infinitesimal cube of material and can be expressed as a non-dimensional change in length or angle of distortion of the cube. Strains are related to the forces acting on the cube, which are known as stress, by a stress-strain curve. The relationship between stress and strain is generally linear and reversible up until the yield point and the deformation is elastic. The linear relationship for a material is known as Young's modulus. Above the yield point, some degree of permanent distortion remains after unloading and is termed plastic deformation. The determination of the stress and strain throughout a solid object is given by the field of strength of materials and for a structure by structural analysis.

In physics and materials science, plasticity is the ability of a solid material to undergo permanent deformation, a non-reversible change of shape in response to applied forces. For example, a solid piece of metal being bent or pounded into a new shape displays plasticity as permanent changes occur within the material itself. In engineering, the transition from elastic behavior to plastic behavior is known as yielding.

In engineering and materials science, a stress–strain curve for a material gives the relationship between stress and strain. It is obtained by gradually applying load to a test coupon and measuring the deformation, from which the stress and strain can be determined. These curves reveal many of the properties of a material, such as the Young's modulus, the yield strength and the ultimate tensile strength.

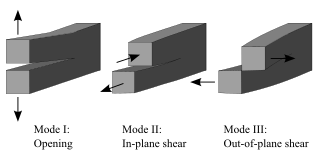

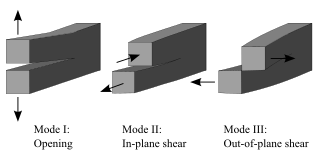

Fracture is the appearance of a crack or complete separation of an object or material into two or more pieces under the action of stress. The fracture of a solid usually occurs due to the development of certain displacement discontinuity surfaces within the solid. If a displacement develops perpendicular to the surface, it is called a normal tensile crack or simply a crack; if a displacement develops tangentially, it is called a shear crack, slip band, or dislocation.

In physics and materials science, elasticity is the ability of a body to resist a distorting influence and to return to its original size and shape when that influence or force is removed. Solid objects will deform when adequate loads are applied to them; if the material is elastic, the object will return to its initial shape and size after removal. This is in contrast to plasticity, in which the object fails to do so and instead remains in its deformed state.

The field of strength of materials typically refers to various methods of calculating the stresses and strains in structural members, such as beams, columns, and shafts. The methods employed to predict the response of a structure under loading and its susceptibility to various failure modes takes into account the properties of the materials such as its yield strength, ultimate strength, Young's modulus, and Poisson's ratio. In addition, the mechanical element's macroscopic properties such as its length, width, thickness, boundary constraints and abrupt changes in geometry such as holes are considered.

In mechanics, compressive strength is the capacity of a material or structure to withstand loads tending to reduce size. In other words, compressive strength resists compression, whereas tensile strength resists tension. In the study of strength of materials, tensile strength, compressive strength, and shear strength can be analyzed independently.

Fracture mechanics is the field of mechanics concerned with the study of the propagation of cracks in materials. It uses methods of analytical solid mechanics to calculate the driving force on a crack and those of experimental solid mechanics to characterize the material's resistance to fracture.

In continuum mechanics, the maximum distortion energy criterion states that yielding of a ductile material begins when the second invariant of deviatoric stress reaches a critical value. It is a part of plasticity theory that mostly applies to ductile materials, such as some metals. Prior to yield, material response can be assumed to be of a nonlinear elastic, viscoelastic, or linear elastic behavior.

In materials science, work hardening, also known as strain hardening, is the strengthening of a metal or polymer by plastic deformation. Work hardening may be desirable, undesirable, or inconsequential, depending on the context.

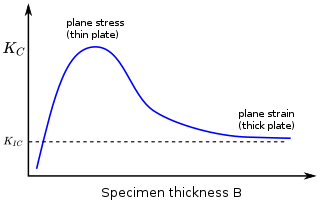

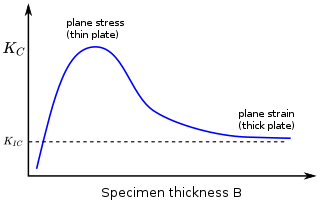

In materials science, fracture toughness is the critical stress intensity factor of a sharp crack where propagation of the crack suddenly becomes rapid and unlimited. A component's thickness affects the constraint conditions at the tip of a crack with thin components having plane stress conditions and thick components having plane strain conditions. Plane strain conditions give the lowest fracture toughness value which is a material property. The critical value of stress intensity factor in mode I loading measured under plane strain conditions is known as the plane strain fracture toughness, denoted . When a test fails to meet the thickness and other test requirements that are in place to ensure plane strain conditions, the fracture toughness value produced is given the designation . Fracture toughness is a quantitative way of expressing a material's resistance to crack propagation and standard values for a given material are generally available.

The J-integral represents a way to calculate the strain energy release rate, or work (energy) per unit fracture surface area, in a material. The theoretical concept of J-integral was developed in 1967 by G. P. Cherepanov and independently in 1968 by James R. Rice, who showed that an energetic contour path integral was independent of the path around a crack.

The T-failure criterion is a set of material failure criteria that can be used to predict both brittle and ductile failure.

In solid mechanics, the Johnson–Holmquist damage model is used to model the mechanical behavior of damaged brittle materials, such as ceramics, rocks, and concrete, over a range of strain rates. Such materials usually have high compressive strength but low tensile strength and tend to exhibit progressive damage under load due to the growth of microfractures.

The Christensen failure criterion is a material failure theory for isotropic materials that attempts to span the range from ductile to brittle materials. It has a two-property form calibrated by the uniaxial tensile and compressive strengths T and C .

In Earth science, ductility refers to the capacity of a rock to deform to large strains without macroscopic fracturing. Such behavior may occur in unlithified or poorly lithified sediments, in weak materials such as halite or at greater depths in all rock types where higher temperatures promote crystal plasticity and higher confining pressures suppress brittle fracture. In addition, when a material is behaving ductilely, it exhibits a linear stress vs strain relationship past the elastic limit.

According to the classical theories of elastic or plastic structures made from a material with non-random strength (ft), the nominal strength (σN) of a structure is independent of the structure size (D) when geometrically similar structures are considered. Any deviation from this property is called the size effect. For example, conventional strength of materials predicts that a large beam and a tiny beam will fail at the same stress if they are made of the same material. In the real world, because of size effects, a larger beam will fail at a lower stress than a smaller beam.

Polymer fracture is the study of the fracture surface of an already failed material to determine the method of crack formation and extension in polymers both fiber reinforced and otherwise. Failure in polymer components can occur at relatively low stress levels, far below the tensile strength because of four major reasons: long term stress or creep rupture, cyclic stresses or fatigue, the presence of structural flaws and stress-cracking agents. Formations of submicroscopic cracks in polymers under load have been studied by x ray scattering techniques and the main regularities of crack formation under different loading conditions have been analyzed. The low strength of polymers compared to theoretically predicted values are mainly due to the many microscopic imperfections found in the material. These defects namely dislocations, crystalline boundaries, amorphous interlayers and block structure can all lead to the non-uniform distribution of mechanical stress.

Crack tip opening displacement (CTOD) or is the distance between the opposite faces of a crack tip at the 90° intercept position. The position behind the crack tip at which the distance is measured is arbitrary but commonly used is the point where two 45° lines, starting at the crack tip, intersect the crack faces. The parameter is used in fracture mechanics to characterize the loading on a crack and can be related to other crack tip loading parameters such as the stress intensity factor and the elastic-plastic J-integral.

Plasticity theory for rocks is concerned with the response of rocks to loads beyond the elastic limit. Historically, conventional wisdom has it that rock is brittle and fails by fracture while plasticity is identified with ductile materials. In field scale rock masses, structural discontinuities exist in the rock indicating that failure has taken place. Since the rock has not fallen apart, contrary to expectation of brittle behavior, clearly elasticity theory is not the last word.