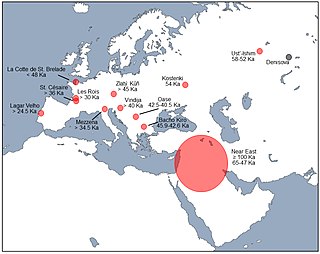

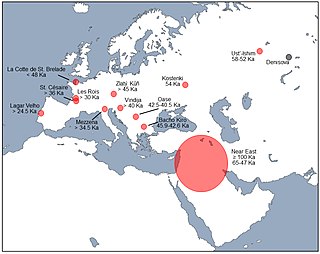

Early modern human (EMH), or anatomically modern human (AMH), are terms used to distinguish Homo sapiens that are anatomically consistent with the range of phenotypes seen in contemporary humans, from extinct archaic human species. This distinction is useful especially for times and regions where anatomically modern and archaic humans co-existed, for example, in Paleolithic Europe. Among the oldest known remains of Homo sapiens are those found at the Omo-Kibish I archaeological site in south-western Ethiopia, dating to about 233,000 to 196,000 years ago, the Florisbad site in South Africa, dating to about 259,000 years ago, and the Jebel Irhoud site in Morocco, dated about 315,000 years ago.

Shanidar Cave is an archaeological site on Bradost Mountain, within the Zagros Mountains in the Erbil Governorate of Kurdistan Region in northern Iraq. Neanderthal remains were discovered here in 1953, including Shanidar 1, who survived several injuries, possibly due to care from others in his group, and Shanidar 4, the famed 'flower burial'. Until this discovery, Cro-Magnons, the earliest known H. sapiens in Europe, were the only individuals known for purposeful, ritualistic burials.

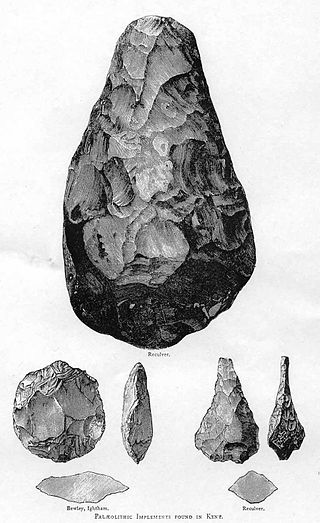

Behavioral modernity is a suite of behavioral and cognitive traits believed to distinguish current Homo sapiens from other anatomically modern humans, hominins, and primates. Most scholars agree that modern human behavior can be characterized by abstract thinking, planning depth, symbolic behavior, music and dance, exploitation of large game, and blade technology, among others. Underlying these behaviors and technological innovations are cognitive and cultural foundations that have been documented experimentally and ethnographically by evolutionary and cultural anthropologists. These human universal patterns include cumulative cultural adaptation, social norms, language, and extensive help and cooperation beyond close kin.

Neanderthals became extinct around 40,000 years ago. Hypotheses on the causes of the extinction include violence, transmission of diseases from modern humans which Neanderthals had no immunity to, competitive replacement, extinction by interbreeding with early modern human populations, natural catastrophes, climate change and inbreeding depression. It is likely that multiple factors caused the demise of an already low population.

Erik Trinkaus is an American paleoanthropologist specializing in Neandertal and early modern human biology and human evolution. Trinkaus researches the evolution of the species Homo sapiens and recent human diversity, focusing on the paleoanthropology and emergence of late archaic and early modern humans, and the subsequent evolution of anatomically modern humanity. Trinkaus is a member of the National Academy of Sciences, and the Mary Tileston Hemenway Professor Emeritus of Arts and Sciences at Washington University in St. Louis. He is a frequent contributor to publications such as Science, Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, PLOS One, American Journal of Physical Anthropology, and the Journal of Human Evolution and has written/co-written or edited/co-edited fifteen books in paleoanthropology. He is frequently quoted in the popular media.

The Neanderthal genome project is an effort of a group of scientists to sequence the Neanderthal genome, founded in July 2006.

The Sidrón Cave is a non-carboniferous limestone karst cave system located in the Piloña municipality of Asturias, northwestern Spain, where Paleolithic rock art and the fossils of more than a dozen Neanderthals were found. Declared a "Partial Natural Reserve" in 1995, the site also serves as a retreat for five species of bats and is the place of discovery of two species of Coleoptera (beetles).

The Grotte du Renne is one of the many caves at Arcy-sur-Cure in France, an archaeological site of the Middle/Upper Paleolithic period in the Yonne departement, Bourgogne-Franche-Comté. It contains Châtelperronian lithic industry and Neanderthal remains. Grotte du Renne has been argued to provide the best evidence that Neanderthals developed aspects of modern behaviour before contact with modern humans, but this has been challenged by radiological dates, which suggest mixing of later human artifacts with Neanderthal remains. However, it has also been argued that the radiometric dates have been affected by post-recovery contamination, and statistical testing suggests the association between Neanderthal remains, Châtelperronian artefacts and personal ornaments is genuine, not the result of post-depositional processes.

The oldest undisputed examples of figurative art are known from Europe and from Sulawesi, Indonesia, dated about 35,000 years old . Together with religion and other cultural universals of contemporary human societies, the emergence of figurative art is a necessary attribute of full behavioral modernity.

Vindija Cave is an archaeological site associated with Neanderthals and modern humans, located in the municipality of Donja Voća, northern Croatia. Remains of three Neanderthals were selected as the primary sources for the first draft sequence of the Neanderthal genome project in 2010. Additional research was done on the samples and published in 2017.

The multiregional hypothesis, multiregional evolution (MRE), or polycentric hypothesis, is a scientific model that provides an alternative explanation to the more widely accepted "Out of Africa" model of monogenesis for the pattern of human evolution.

The Denisovans or Denisova hominins(di-NEE-sə-və) are an extinct species or subspecies of archaic human that ranged across Asia during the Lower and Middle Paleolithic, and lived, based on current evidence, from 285 to 52 thousand years ago. Denisovans are known from few physical remains; consequently, most of what is known about them comes from DNA evidence. No formal species name has been established pending more complete fossil material.

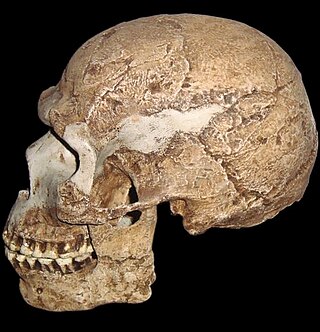

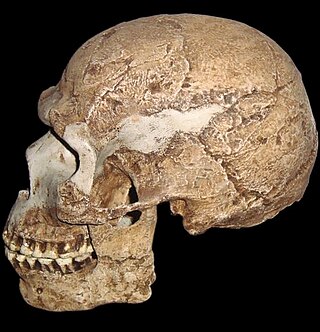

Neanderthals are an extinct group of archaic humans who lived in Eurasia until about 40,000 years ago. The type specimen, Neanderthal 1, was found in 1856 in the Neander Valley in present-day Germany.

Neanderthal anatomy differed from modern humans in that they had a more robust build and distinctive morphological features, especially on the cranium, which gradually accumulated more derived aspects, particularly in certain isolated geographic regions. This robust build was an effective adaptation for Neanderthals, as they lived in the cold environments of Europe. In which they also had to operate in Europe's dense forest landscape that was extremely different from the environments of the African grassland plains that Homo sapiens adapted to with a different anatomical build.

Interbreeding between archaic and modern humans occurred during the Middle Paleolithic and early Upper Paleolithic. The interbreeding happened in several independent events that included Neanderthals and Denisovans, as well as several unidentified hominins.

Mezmaiskaya Cave is a prehistoric cave site overlooking the right bank of the Sukhoi Kurdzhips in the southern Russian Republic of Adygea, located in the northwestern foothills of the North Caucasus in the Caucasus Mountains system.

Southwest Asian Neanderthals were Neanderthals who lived in Turkey, Lebanon, Syria, Israel, Palestine, Iraq, and Iran - the southernmost expanse of the known Neanderthal range. Although their arrival in Asia is not well-dated, early Neanderthals occupied the region apparently until about 100,000 years ago. At this time, Homo sapiens immigrants seem to have replaced them in one of the first anatomically-modern expansions out of Africa. In their turn, starting around 80,000 years ago, Neanderthals seem to have returned and replaced Homo sapiens in Southwest Asia. They inhabited the region until about 55,000 years ago.

The Goyet Caves are a series of connected caves located in Belgium in a limestone cliff about 15 m (50 ft) above the river Samson near the village of Mozet in the Gesves municipality of the Namur province. The site is a significant locality of regional Neanderthal and European early modern human occupation, as thousands of fossils and artifacts were discovered that are all attributed to a long and contiguous stratigraphic sequence from 120,000 years ago, the Middle Paleolithic to less than 5,000 years ago, the late Neolithic. A robust sequence of sediments was identified during extensive excavations by geologist Edouard Dupont, who undertook the first probings as early as 1867. The site was added to the Belgian National Heritage register in 1976.

Kebara 2 is a 60,000 year-old Levantine Neanderthal mid-body male skeleton. It was discovered in 1983 by Ofer Bar-Yosef, Baruch Arensburg, and Bernard Vandermeersch in a Mousterian layer of Kebara Cave, Israel. To the excavators, its disposition suggested it had been deliberately buried, though like every other putative Middle Palaeolithic intentional burial, this has been questioned.

Krapina Neanderthal site, also known as Hušnjakovo Hill is a Paleolithic archaeological site located near Krapina, Croatia.