In mechanics, acceleration is the rate of change of the velocity of an object with respect to time. Acceleration is one of several components of kinematics, the study of motion. Accelerations are vector quantities. The orientation of an object's acceleration is given by the orientation of the net force acting on that object. The magnitude of an object's acceleration, as described by Newton's Second Law, is the combined effect of two causes:

A centripetal force is a force that makes a body follow a curved path. The direction of the centripetal force is always orthogonal to the motion of the body and towards the fixed point of the instantaneous center of curvature of the path. Isaac Newton described it as "a force by which bodies are drawn or impelled, or in any way tend, towards a point as to a centre". In Newtonian mechanics, gravity provides the centripetal force causing astronomical orbits.

In physics and mechanics, torque is the rotational analogue of linear force. It is also referred to as the moment of force. Just as a linear force is a push or a pull applied to a body, a torque can be thought of as a twist applied to an object with respect to a chosen point; for example, driving a screw uses torque, which is applied by the screwdriver rotating around its axis. A force of three newtons applied two metres from the fulcrum, for example, exerts the same torque as a force of one newton applied six metres from the fulcrum. The symbol for torque is typically , the lowercase Greek letter tau. When being referred to as moment of force, it is commonly denoted by M.

The Navier–Stokes equations are partial differential equations which describe the motion of viscous fluid substances. They were named after French engineer and physicist Claude-Louis Navier and the Irish physicist and mathematician George Gabriel Stokes. They were developed over several decades of progressively building the theories, from 1822 (Navier) to 1842–1850 (Stokes).

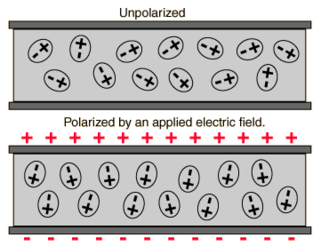

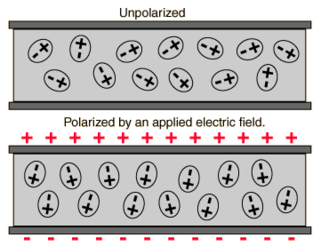

In electromagnetism, the absolute permittivity, often simply called permittivity and denoted by the Greek letter ε (epsilon), is a measure of the electric polarizability of a dielectric. A material with high permittivity polarizes more in response to an applied electric field than a material with low permittivity, thereby storing more energy in the material. In electrostatics, the permittivity plays an important role in determining the capacitance of a capacitor.

Kinematics is a subfield of physics and mathematics, developed in classical mechanics, that describes the motion of points, bodies (objects), and systems of bodies without considering the forces that cause them to move. Kinematics, as a field of study, is often referred to as the "geometry of motion" and is occasionally seen as a branch of both applied and pure mathematics since it can be studied without considering the mass of a body or the forces acting upon it. A kinematics problem begins by describing the geometry of the system and declaring the initial conditions of any known values of position, velocity and/or acceleration of points within the system. Then, using arguments from geometry, the position, velocity and acceleration of any unknown parts of the system can be determined. The study of how forces act on bodies falls within kinetics, not kinematics. For further details, see analytical dynamics.

In physics, work is the energy transferred to or from an object via the application of force along a displacement. In its simplest form, for a constant force aligned with the direction of motion, the work equals the product of the force strength and the distance traveled. A force is said to do positive work if when applied it has a component in the direction of the displacement of the point of application. A force does negative work if it has a component opposite to the direction of the displacement at the point of application of the force.

In physics, a Langevin equation is a stochastic differential equation describing how a system evolves when subjected to a combination of deterministic and fluctuating ("random") forces. The dependent variables in a Langevin equation typically are collective (macroscopic) variables changing only slowly in comparison to the other (microscopic) variables of the system. The fast (microscopic) variables are responsible for the stochastic nature of the Langevin equation. One application is to Brownian motion, which models the fluctuating motion of a small particle in a fluid.

In statistical mechanics and information theory, the Fokker–Planck equation is a partial differential equation that describes the time evolution of the probability density function of the velocity of a particle under the influence of drag forces and random forces, as in Brownian motion. The equation can be generalized to other observables as well. The Fokker-Planck equation has multiple applications in information theory, graph theory, data science, finance, economics etc.

The short-time Fourier transform (STFT), is a Fourier-related transform used to determine the sinusoidal frequency and phase content of local sections of a signal as it changes over time. In practice, the procedure for computing STFTs is to divide a longer time signal into shorter segments of equal length and then compute the Fourier transform separately on each shorter segment. This reveals the Fourier spectrum on each shorter segment. One then usually plots the changing spectra as a function of time, known as a spectrogram or waterfall plot, such as commonly used in software defined radio (SDR) based spectrum displays. Full bandwidth displays covering the whole range of an SDR commonly use fast Fourier transforms (FFTs) with 2^24 points on desktop computers.

In quantum physics, Fermi's golden rule is a formula that describes the transition rate from one energy eigenstate of a quantum system to a group of energy eigenstates in a continuum, as a result of a weak perturbation. This transition rate is effectively independent of time and is proportional to the strength of the coupling between the initial and final states of the system as well as the density of states. It is also applicable when the final state is discrete, i.e. it is not part of a continuum, if there is some decoherence in the process, like relaxation or collision of the atoms, or like noise in the perturbation, in which case the density of states is replaced by the reciprocal of the decoherence bandwidth.

In electrodynamics, Poynting's theorem is a statement of conservation of energy for electromagnetic fields developed by British physicist John Henry Poynting. It states that in a given volume, the stored energy changes at a rate given by the work done on the charges within the volume, minus the rate at which energy leaves the volume. It is only strictly true in media which is not dispersive, but can be extended for the dispersive case. The theorem is analogous to the work-energy theorem in classical mechanics, and mathematically similar to the continuity equation.

In mechanics, virtual work arises in the application of the principle of least action to the study of forces and movement of a mechanical system. The work of a force acting on a particle as it moves along a displacement is different for different displacements. Among all the possible displacements that a particle may follow, called virtual displacements, one will minimize the action. This displacement is therefore the displacement followed by the particle according to the principle of least action.

The work of a force on a particle along a virtual displacement is known as the virtual work.

In radiometry, radiant flux or radiant power is the radiant energy emitted, reflected, transmitted, or received per unit time, and spectral flux or spectral power is the radiant flux per unit frequency or wavelength, depending on whether the spectrum is taken as a function of frequency or of wavelength. The SI unit of radiant flux is the watt (W), one joule per second, while that of spectral flux in frequency is the watt per hertz and that of spectral flux in wavelength is the watt per metre —commonly the watt per nanometre.

In differential calculus, the Reynolds transport theorem, or simply the Reynolds theorem, named after Osborne Reynolds (1842–1912), is a three-dimensional generalization of the Leibniz integral rule. It is used to recast time derivatives of integrated quantities and is useful in formulating the basic equations of continuum mechanics.

The Cauchy momentum equation is a vector partial differential equation put forth by Cauchy that describes the non-relativistic momentum transport in any continuum.

Linear motion, also called rectilinear motion, is one-dimensional motion along a straight line, and can therefore be described mathematically using only one spatial dimension. The linear motion can be of two types: uniform linear motion, with constant velocity ; and non-uniform linear motion, with variable velocity. The motion of a particle along a line can be described by its position , which varies with (time). An example of linear motion is an athlete running a 100-meter dash along a straight track.

Velocity is the speed in combination with the direction of motion of an object. Velocity is a fundamental concept in kinematics, the branch of classical mechanics that describes the motion of bodies.

In classical mechanics, the central-force problem is to determine the motion of a particle in a single central potential field. A central force is a force that points from the particle directly towards a fixed point in space, the center, and whose magnitude only depends on the distance of the object to the center. In a few important cases, the problem can be solved analytically, i.e., in terms of well-studied functions such as trigonometric functions.