The Madagascar Armed Forces is the national military of Madagascar. The IISS detailed the armed forces in 2012 as including an Army of 12,500+, a Navy of 500, and a 500-strong Air Force.

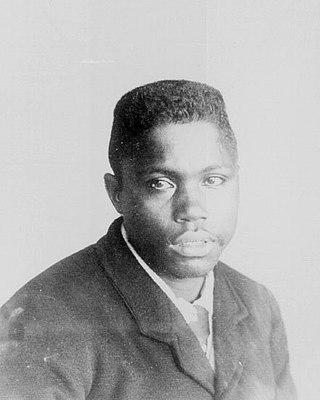

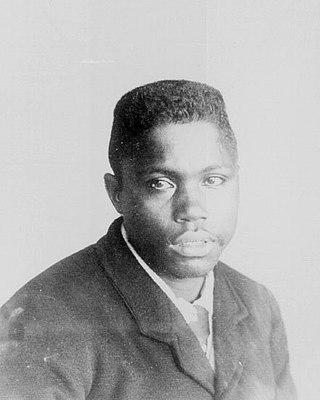

Radama I "the Great" (1793–1828) was the first Malagasy sovereign to be recognized as King of Madagascar (1810–1828) by a European state. He came to power at the age of 17 following the death of his father, King Andrianampoinimerina. Under Radama's rule and at his invitation, the first Europeans entered his central highland Kingdom of Imerina and its capital at Antananarivo. Radama encouraged these London Missionary Society envoys to establish schools to teach tradecraft and literacy to nobles and potential military and civil service recruits; they also introduced Christianity and taught literacy using the translated Bible. A wide range of political and social reforms were enacted under his rule, including an end to the international slave trade, which had historically been a key source of wealth and armaments for the Merina monarchy. Through aggressive military campaigns he successfully united two-thirds of the island under his rule. Abuse of alcohol weakened his health and he died prematurely at age 35. He was succeeded by his highest-ranking wife, Ranavalona I.

Ranavalona I, also known as Ranavalo-Manjaka I and the “Mad Monarch of Madagascar” was sovereign of the Kingdom of Madagascar from 1828 to 1861. After positioning herself as queen following the death of her young husband, Radama I, Ranavalona pursued a policy of isolationism and self-sufficiency, reducing economic and political ties with European powers, repelling a French attack on the coastal town of Foulpointe, and taking vigorous measures to eradicate the small but growing Malagasy Christian movement initiated under Radama I by members of the London Missionary Society.

The Merina people are the largest ethnic group in Madagascar. They are the "highlander" Malagasy ethnic group of the African island and one of the country's eighteen official ethnic groups. Their origins are mixed, predominantly with Austronesians arriving before the 5th century AD, then many centuries later with mostly Bantu Africans, but also some other ethnic groups. They speak the Merina dialect of the official Malagasy language of Madagascar.

Andrianampoinimerina (1745–1810) ruled the Kingdom of Imerina on Madagascar from 1787 until his death. His reign was marked by the reunification of Imerina following 77 years of civil war, and the subsequent expansion of his kingdom into neighboring territories, thereby initiating the unification of Madagascar under Merina rule. Andrianampoinimerina is a cultural hero and holds near mythic status among the Merina people, and is considered one of the greatest military and political leaders in the history of Madagascar.

Ambohimanga is a hill and traditional fortified royal settlement (rova) in Madagascar, located approximately 24 kilometers (15 mi) northeast of the capital city of Antananarivo. It is situated in the commune of Ambohimanga Rova.

Andriana was both the noble class and a title of nobility in Madagascar. Historically, many Malagasy ethnic groups lived in highly stratified caste-based social orders in which the andriana were the highest strata. They were above the Hova and Andevo (slaves). The Andriana and the Hova were a part of Fotsy, while the Andevo were Mainty in local terminology.

The Merina Kingdom, or Kingdom of Madagascar, officially the Kingdom of Imerina, was a pre-colonial state off the coast of Southeast Africa that, by the 18th century, dominated most of what is now Madagascar. It spread outward from Imerina, the Central Highlands region primarily inhabited by the Merina ethnic group with a spiritual capital at Ambohimanga and a political capital 24 km (15 mi) west at Antananarivo, currently the seat of government for the modern state of Madagascar. The Merina kings and queens who ruled over greater Madagascar in the 19th century were the descendants of a long line of hereditary Merina royalty originating with Andriamanelo, who is traditionally credited with founding Imerina in 1540.

Andriamanelo was king of Alasora in the central highlands region of Madagascar. He is generally considered by historians to be the founder of the Kingdom of Imerina and originator of the Merina royal line that, by the 19th century, had extended its rule over virtually all of Madagascar. The son of a Vazimba mother and a man of the newly arrived Hova people originating in southeast Madagascar, Andriamanelo ultimately led a series of military campaigns against the Vazimba, beginning a several-decade process to drive them from the Highlands. The conflict that defined his reign also produced many lasting innovations, including the development of fortified villages in the highlands and the use of iron weapons. Oral tradition furthermore credits Andriamanelo with establishing a ruling class of nobles (andriana) and defining the rules of succession. Numerous cultural traditions, including the ritual of circumcision, the wedding custom of vodiondry and the art of Malagasy astrology (sikidy) are likewise associated with this king.

Ralambo was the ruler of the Kingdom of Imerina in the central Highlands region of Madagascar from 1575 to 1612. Ruling from Ambohidrabiby, Ralambo expanded the realm of his father, Andriamanelo, and was the first to assign the name of Imerina to the region. Oral history has preserved numerous legends about this king, including several dramatic military victories, contributing to his heroic and near-mythical status among the kings of ancient Imerina. The circumstances surrounding his birth, which occurred on the highly auspicious date of the first of the year, are said to be supernatural in nature and further add to the mystique of this sovereign.

Andrianjaka reigned over the Kingdom of Imerina in the central highlands region of Madagascar from around 1612 to 1630. Despite being the younger of King Ralambo's two sons, Andrianjaka succeeded to the throne on the basis of his strength of character and skill as a military tactician. The most celebrated accomplishment of his reign was the capture of the hill of Analamanga from a Vazimba king. There he established the fortified compound (rova) that would form the heart of his new capital city of Antananarivo. Upon his orders, the first structures within this fortified compound were constructed: several traditional royal houses were built, and plans for a series of royal tombs were designed. These buildings took on an enduring political and spiritual significance, ensuring their preservation until being destroyed by fire in 1995. Andrianjaka obtained a sizable cache of firearms and gunpowder, materials that helped to establish and preserve his dominance and expand his rule over greater Imerina.

The twelve sacred hills of Imerina are hills of historical significance to the Merina people of Madagascar. Located throughout Imerina, the central area of the highlands of Madagascar, the sites were often ancient capitals, the birthplaces of key public figures, or the tomb sites of esteemed political or spiritual leaders. The first set of sacred sites was designated by early 17th-century king Andrianjaka. The notion was re-sanctified under late 18th-century king Andrianampoinimerina, who replaced several of the earlier sites with new ones. More than 12 sites were thus designated as sacred over time, although the notion of twelve sacred hills was perpetuated because of the significance of the number 12 in Malagasy cosmology. Today, little concrete evidence of the former importance of many of these sites remains, but the significant archeological and cultural heritage of several of the sites has been preserved. The historic significance of the sites is best represented by the Rova of Antananarivo at Analamanga, the ancient fortified city at Alasora, the houses and tombs of the andriana at Antsahadinta and the ancient fortifications and palaces at Ambohimanga, protected as a UNESCO World Heritage Site since 2001.

The Antemoro are an ethnic group of Madagascar living on the southeastern coast, mostly between Manakara and Farafangana. Numbering around 500,000, this ethnic group mostly traces its origins back to East African Bantu and Indonesian Austronesian speakers like most other Malagasy. A minority of them belonging to the Anteony (aristocrats), Antalaotra or Anakara clans claim being descendants of settlers who arrived from Arabia, Persia but more likely Somalia from Dir part of the human Haplogroup T-M184; the Islamic religion was soon abandoned in favor of traditional beliefs and practices associated with respect for the ancestors, although remnants of Islam remain in fady such as the prohibition against consuming pork. In the 16th century an Antemoro kingdom was established, supplanting the power of the earlier Zafiraminia, who descended from seafarers of Sumatran origin.

The Antaifasy are an ethnic group of Madagascar inhabiting the southeast coastal region around Farafangana. Historically a fishing and farming people, many Antaifasy were heavily conscripted into forced labor (fanampoana) and brought to Antananarivo as slaves under the 19th century authority of the Kingdom of Imerina. Antaifasy society was historically divided into three groups, each ruled by a king and strongly concentrated around the constraints of traditional moral codes. Approximately 150,000 Antaifasy inhabit Madagascar as of 2013.

The Bezanozano are believed to be one of the earliest Malagasy ethnic groups to establish themselves in Madagascar, where they inhabit an inland area between the Betsimisaraka lowlands and the Merina highlands. They are associated with the vazimba, the earliest inhabitants of Madagascar, and the many vazimba tombs throughout Bezanozano territory are sites of pilgrimage, ritual and sacrifice, although the Bezanozano believe the descendants among them of these most ancient of ancestors cannot be identified or known. Their name means "those of many small plaits" in reference to their traditional hairstyle, and like the Merina they practice the famadihana reburial ceremony. There were around 100,000 Bezanozano living in Madagascar in 2013.

The Sihanaka are a Malagasy ethnic group concentrated around Lake Alaotra and the town of Ambatondrazaka in central northeastern Madagascar. Their name means the "people of the swamps" in reference to the marshlands around Lake Alaotra that they inhabit. While rice has long been the principal crop of the region, by the 17th century, the Sihanaka had also become wealthy traders in slaves and other goods, capitalizing on their position on the main trade route between the capital of the neighboring Kingdom of Imerina at Antananarivo and the eastern port of Toamasina. At the turn of the 19th century they came under the control of the Boina Kingdom before submitting to Imerina, which went on to rule over the majority of Madagascar. Today the Sihanaka practice intensive agriculture and rice yields are higher in this region than elsewhere, placing strain on the many unique plant and animal species that depend on the Lake Alaotra ecosystem for survival.

The Tanala are a Malagasy ethnic group that inhabit a forested inland region of south-east Madagascar near Manakara. Their name means "people of the forest." Tanala people identify with one of two sub-groups: the southern Ikongo group, who managed to remain independent in the face of the expanding Kingdom of Imerina in the 19th century, or the northern Menabe group, who submitted to Merina rule. Both groups trace their origin back to a noble ancestor named Ralambo, who is believed to be of Arab descent. They were historically known to be great warriors, having led a successful conquest of the neighboring Antemoro people in the 18th century. They are also reputed to have particular talent in divination through reading seeds or through astrology, which was brought to Madagascar with the Arabs.

The Fandroana, termed the Royal Bath by 19th century European historians, is the annual New Year's festival of the Merina people inhabiting the highlands of central Madagascar. The origins of the festival are preserved through oral history. According to folk legend, the wild zebu cattle that roamed the Highlands were first domesticated for food in Imerina under the reign of Ralambo. Different legends attribute the discovery that zebu were edible to the king's servant or to Ralambo himself. Ralambo is credited with founding the traditional ceremony of the fandroana to celebrate this discovery, although others have suggested he merely added certain practices to the celebration of a long-standing ritual.

The Hova, or free commoners, were one of the three principal historical castes in the Merina Kingdom of Madagascar, alongside the Andriana (nobles) and Andevo (slaves). The term hova originally applied to all members of a Malagasy clan that migrated into the central highlands from the southeast coast of the island around the 15th century and absorbed the existing population of Vazimba. Andriamanelo (1540–1575) consolidated the power of the Hova when he united many of the Hova chiefdoms around Antananarivo under his rule. The term Hova remained in use through the 20th century, though some foreigners transliterated that word to be Ankova, and increasingly used since the 19th century.

A rova is a fortified royal complex built in the central highlands of Madagascar by Merina of the Andriana (noble) class. The first rova was established at Alasora by king Andriamanelo around 1540 to protect his residence throughout a war with the neighboring Vazimba. Rovas are organized according to traditional symbolic notions of space and enclose the royal residences, the tomb of the founder, and a town square marked with a stone. They are protected with walls, trenches and stone gateways and are planted with fig trees symbolic of royalty.