The history of North Korea began with the end of World War II in 1945. The surrender of Japan led to the division of Korea at the 38th parallel, with the Soviet Union occupying the north, and the United States occupying the south. The Soviet Union and the United States failed to agree on a way to unify the country, and in 1948, they established two separate governments – the Soviet-aligned Democratic People's Republic of Korea and the American-aligned Republic of Korea – each claiming to be the legitimate government of all of Korea.

The history of South Korea begins with the Japanese surrender on 2 September 1945. At that time, South Korea and North Korea were divided, despite being the same people and on the same peninsula. In 1950, the Korean War broke out. North Korea overran South Korea until US-lead UN forces intervened. At the end of the war in 1953, the border between South and North remained largely similar. Tensions between the two sides continued. South Korea alternated between dictatorship and liberal democracy. It underwent substantial economic development.

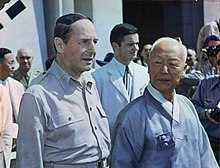

Syngman Rhee was a South Korean politician who served as the first president of South Korea from 1948 to 1960. Rhee is also known by his art name Unam. Rhee was also the first and last president of the Provisional Government of the Republic of Korea from 1919 to his impeachment in 1925 and from 1947 to 1948. As president of South Korea, Rhee's government was characterised by authoritarianism, limited economic development, and in the late 1950s growing political instability and public opposition.

The Korean conflict is an ongoing conflict based on the division of Korea between North Korea and South Korea, both of which claim to be the sole legitimate government of all of Korea. During the Cold War, North Korea was backed by the Soviet Union, China, and other allies, while South Korea was backed by the United States, United Kingdom, and other Western allies.

The division of Korea began on August 15, 1945 when the official announcement of the surrender of Japan was released, thus ending the Pacific Theater of World War II. During the war, the Allied leaders had already been considering the question of Korea's future following Japan's eventual surrender in the war. The leaders reached an understanding that Korea would be liberated from Japan but would be placed under an international trusteeship until the Koreans would be deemed ready for self-rule. In the last days of the war, the United States proposed dividing the Korean peninsula into two occupation zones with the 38th parallel as the dividing line. The Soviets accepted their proposal and agreed to divide Korea.

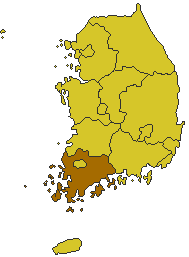

The Jeju uprising, known in South Korea as the Jeju April 3 incident, was an uprising on Jeju Island from April 1948 to May 1949. A year prior to its start, residents of Jeju had begun protesting elections scheduled by the United Nations Temporary Commission on Korea (UNTCOK) to be held in the United States-occupied half of Korea, which they believed would entrench the division of the country. A general strike was later organised by the Workers' Party of South Korea (WPSK) from February to March 1948. The WPSK launched an insurgency in April 1948, attacking police and Northwest Youth League members stationed on Jeju who had been mobilized to suppress the protests by force. The First Republic of Korea under President Syngman Rhee escalated the suppression of the uprising from August 1948, declaring martial law in November and beginning an "eradication campaign" against rebel forces in the rural areas of Jeju in March 1949, defeating them within two months. Many rebel veterans and suspected sympathizers were later killed upon the outbreak of the Korean War in June 1950, and the existence of the Jeju uprising was officially censored and repressed in South Korea for several decades.

The first Republic of Korea was the government of South Korea from August 1948 to April 1960. The first republic was founded on 15 August 1948 after the transfer from the United States Army Military Government that governed South Korea since the end of Japanese rule in 1945, becoming the first independent republican government in Korea. Syngman Rhee became the first president of South Korea following the May 1948 general election, and the National Assembly in Seoul promulgated South Korea's first constitution in July, establishing a presidential system of government.

The People's Republic of Korea was a short-lived provisional government that was organized at the time of the surrender of the Empire of Japan at the end of World War II. It was proclaimed on 6 September 1945, as Korea was being divided into two occupation zones, with the Soviet Union occupying the north and the United States occupying the south. Based on a network of people's committees, it presented a program of radical social change.

Constitutional Assembly elections were held in South Korea on 10 May 1948. They were held under the U.S. military occupation, with supervision from the United Nations, and resulted in a victory for the National Association for the Rapid Realisation of Korean Independence, which won 55 of the 200 seats, although 85 were held by independents. Voter turnout was 95%.

The Korea Democratic Party was the leading opposition party in the first years of the First Republic of Korea. It existed from 1945 to 1949, when it merged with other opposition parties.

The Supreme Council for National Reconstruction (Korean: 국가재건최고회의) was the ruling military junta of South Korea from May 1961 to December 1963.

The second Republic of Korea was the government of South Korea from April 1960 to May 1961.

Pak Hon-yong was a Korean independence activist, politician, philosopher, communist activist and one of the main leaders of the Korean communist movement during Japan's colonial rule (1910–1945). His nickname was Ijong (이정) and Ichun (이춘), his courtesy name being Togyong (덕영).

Chough Pyung-ok was a South Korean politician. He ran against incumbent president Syngman Rhee in the 1960 presidential election but died on February 15, one month before the election on March 15. Rhee received 90% of the vote. He was the first Director of the Korean National Police from 1945 to 1949 and Minister of Home Affairs during the early stages of the Korean War.

The Yeosu-Suncheon rebellion, also known as the Yeo-Sun incident, was a rebellion that began in October 1948 and mostly ended by November of the same year. However, pockets of resistance lasted through to 1957, almost 10 years later.

The Autumn Uprising of 1946, also called the 10.1 Daegu Uprising of 1946 was a peasant uprising in South Korea against the policies of the United States Army Military Government in Korea headed by General John R. Hodge and in favor of restoration of power to the people's committees that made up the People's Republic of Korea. The uprising is also sometimes called the Daegu Riot or Daegu Resistance Movement. The Truth and Reconciliation Commission of South Korea uses a neutral name, the Daegu October Incident.

Operation Blacklist Forty was the codename for the United States occupation of Korea between 1945 and 1948. Following the end of World War II, U.S. forces landed within the present-day South Korea to accept the surrender of the Japanese, and help create an independent and unified Korean government with the help of the Soviet Union, which occupied the present-day North Korea. However, when this effort proved unsuccessful, the United States and the Soviet Union both established their own friendly governments, resulting in the current division of the Korean Peninsula.

Events from the year 1948 in South Korea.

Elections to the Interim Legislative Assembly were held in South Korea in October 1946.

The September 1946 Korean general strike was a nationwide strike led by the Communist Party of Korea in which more than 250,000 workers participated. It was fuelled by a growing independence movement after the imposition of the United States Army Military Government in Korea (USAMGIK). Although the strike's events were studied by the South Korean Truth and Reconciliation Commission from 2005 to 2010, they remain disputed.

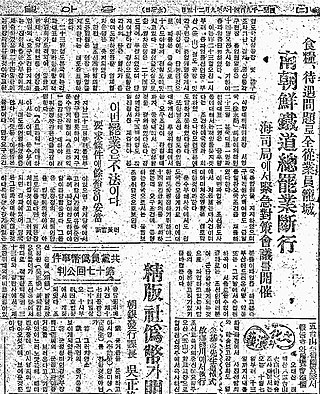

![Anti-trusteeship movement [ko] protest, December 1945 Anti-Trusteeship Campaign.jpg](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/f/fe/Anti-Trusteeship_Campaign.jpg/170px-Anti-Trusteeship_Campaign.jpg)