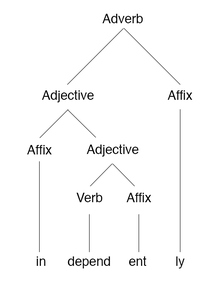

In linguistics, an affix is a morpheme that is attached to a word stem to form a new word or word form. The main two categories are derivational and inflectional affixes. The first ones, such as -un, -ation, anti-, pre- etc, introduce a semantic change to the word they are attached to. The latter ones introduce a syntactic change, such as singular into plural, or present simple tense into present continuous or past tense by adding -ing, -ed to an English word. All of them are bound morphemes by definition; prefixes and suffixes may be separable affixes.

A morpheme is the smallest meaningful constituent of a linguistic expression. The field of linguistic study dedicated to morphemes is called morphology.

In linguistics, morphology is the study of words, including the principles by which they are formed, and how they relate to one another within a language. Most approaches to morphology investigate the structure of words in terms of morphemes, which are the smallest units in a language with some independent meaning. Morphemes include roots that can exist as words by themselves, but also categories such as affixes that can only appear as part of a larger word. For example, in English the root catch and the suffix -ing are both morphemes; catch may appear as its own word, or it may be combined with -ing to form the new word catching. Morphology also analyzes how words behave as parts of speech, and how they may be inflected to express grammatical categories including number, tense, and aspect. Concepts such as productivity are concerned with how speakers create words in specific contexts, which evolves over the history of a language.

Morphological derivation, in linguistics, is the process of forming a new word from an existing word, often by adding a prefix or suffix, such as un- or -ness. For example, unhappy and happiness derive from the root word happy.

Madí—also known as Jamamadí after one of its dialects, and also Kapaná or Kanamanti (Canamanti)—is an Arawan language spoken by about 1,000 Jamamadi, Banawá, and Jarawara people scattered over Amazonas, Brazil.

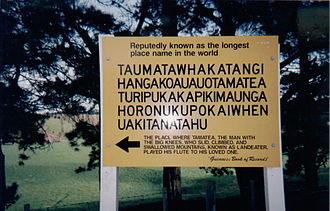

Morphological typology is a way of classifying the languages of the world that groups languages according to their common morphological structures. The field organizes languages on the basis of how those languages form words by combining morphemes. Analytic languages contain very little inflection, instead relying on features like word order and auxiliary words to convey meaning. Synthetic languages, ones that are not analytic, are divided into two categories: agglutinative and fusional languages. Agglutinative languages rely primarily on discrete particles for inflection, while fusional languages "fuse" inflectional categories together, often allowing one word ending to contain several categories, such that the original root can be difficult to extract. A further subcategory of agglutinative languages are polysynthetic languages, which take agglutination to a higher level by constructing entire sentences, including nouns, as one word.

In linguistics, a word stem is a part of a word responsible for its lexical meaning. Typically, a stem remains unmodified during inflection with few exceptions due to apophony

The Tonkawa language was spoken in Oklahoma, Texas, and New Mexico by the Tonkawa people. A language isolate, with no known related languages, Tonkawa has not had L1 speakers since the mid 1900s. Most Tonkawa people now only speak English, but revitalization is underway.

In linguistics, apophony is any alternation within a word that indicates grammatical information.

In historical linguistics, grammaticalization is a process of language change by which words representing objects and actions become grammatical markers. Thus it creates new function words from content words, rather than deriving them from existing bound, inflectional constructions. For example, the Old English verb willan 'to want', 'to wish' has become the Modern English auxiliary verb will, which expresses intention or simply futurity. Some concepts are often grammaticalized, while others, such as evidentiality, are not so much.

Eastern Pomo, also known as Clear Lake Pomo, is a nearly extinct Pomoan language spoken around Clear Lake in Lake County, California by one of the Pomo peoples.

Timucua is a language isolate formerly spoken in northern and central Florida and southern Georgia by the Timucua peoples. Timucua was the primary language used in the area at the time of Spanish colonization in Florida. Differences among the nine or ten Timucua dialects were slight, and appeared to serve mostly to delineate band or tribal boundaries. Some linguists suggest that the Tawasa of what is now northern Alabama may have spoken Timucua, but this is disputed.

In linguistics, a suprafix is a type of affix that gives a suprasegmental pattern to either a neutral base or a base with a preexisting suprasegmental pattern. This affix will, then, convey a derivational or inflectional meaning. This suprasegmental pattern acts like segmental phonemes within a morpheme; the suprafix is a combination of suprasegmental phonemes, organized into a pattern, that creates a morpheme. For example, a number of African languages express tense / aspect distinctions by tone. English has a process of changing stress on verbs to create nouns.

Tübatulabal is an Uto-Aztecan language, traditionally spoken in Kern County, California, United States. It is the traditional language of the Tübatulabal, who still speak the traditional language in addition to English. The language originally had three main dialects: Bakalanchi, Pakanapul and Palegawan.

In linguistics, a suffix is an affix which is placed after the stem of a word. Common examples are case endings, which indicate the grammatical case of nouns and adjectives, and verb endings, which form the conjugation of verbs. Suffixes can carry grammatical information or lexical information . Inflection changes the grammatical properties of a word within its syntactic category. Derivational suffixes fall into two categories: class-changing derivation and class-maintaining derivation.

Central Alaskan Yupʼik is one of the languages of the Yupik family, in turn a member of the Eskimo–Aleut language group, spoken in western and southwestern Alaska. Both in ethnic population and in number of speakers, the Central Alaskan Yupik people form the largest group among Alaska Natives. As of 2010 Yupʼik was, after Navajo, the second most spoken aboriginal language in the United States. Yupʼik should not be confused with the related language Central Siberian Yupik spoken in Chukotka and St. Lawrence Island, nor Naukan Yupik likewise spoken in Chukotka.

This article presents a brief overview of the grammar of the Sesotho and provides links to more detailed articles.

The Nukak language is a language of uncertain classification, perhaps part of the macrofamily Puinave-Maku. It is very closely related to Kakwa.

Odia grammar is the study of the morphological and syntactic structures, word order, case inflections, verb conjugation and other grammatical structures of Odia, an Indo-Aryan language spoken in South Asia.

In linguistic morphology, inflection is a process of word formation in which a word is modified to express different grammatical categories such as tense, case, voice, aspect, person, number, gender, mood, animacy, and definiteness. The inflection of verbs is called conjugation, and one can refer to the inflection of nouns, adjectives, adverbs, pronouns, determiners, participles, prepositions and postpositions, numerals, articles, etc., as declension.