Sixth Street is a historic street and entertainment district in Austin, Texas, located within the city's urban core in downtown Austin. Sixth Street was formerly named Pecan Street under Austin's older naming convention, which had east–west streets named after trees and north–south streets named after Texas rivers.

Hyde Park is a neighborhood and historic district in Austin, Texas. Located in Central Austin, Hyde Park is defined by 38th Street to the south, 45th Street to the north, Duval Street to the east, and Guadalupe Street to the west. It is situated just north of the University of Texas and borders the neighborhoods of Hancock and North Loop.

The Old West Austin Historic District is a residential community in Austin, Texas, United States. It is composed of three neighborhoods located on a plateau just west of downtown Austin: Old Enfield, Pemberton Heights, and Bryker Woods. Developed between 1886 and 1953, the three historic neighborhoods stretch from Mopac Expressway east to Lamar Boulevard, and from 13th Street north to 35th Street. It borders Clarksville Historic District and the West Line Historic District to the south.

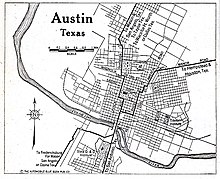

After declaring its independence from Mexico in March, 1836, the Republic of Texas had numerous locations as its seat of government. This being seen as a problem attempts were made to select a permanent site for the capital. January, 1839, with Mirabeau B. Lamar as the newly elected president, a site selection commission of five commissioners was formed. Edward Burleson had surveyed the planned townsite of Waterloo, near the mouth of Shoal Creek on the Colorado River, in 1838; it was incorporated January 1839. By April of that year the site selection commission had selected Waterloo to be the new capital. A bill previously passed by Congress in May, 1838, specified that any site selected as the new capital would be named Austin, after the late Stephen F. Austin; hence Waterloo upon selection as the capital was renamed Austin. The first lots in Austin went on sale August 1839.

The Clarksville Historic District in Austin, Texas, is an area located west of downtown Austin near Lady Bird Lake and just northeast of the intersection of the Missouri Pacific Railroad and West Tenth Street. Many historic homes and structures are located within the Clarksville Historic District. While Clarksville is geographically part of the Old West Austin Historic District, it is distinct from the two historic neighborhoods of Old Enfield, which lies immediately to the north on the eastern side of Texas State Highway Loop 1, and Tarrytown, which is situated to the west and northwest on the western side of Mopac.

West Campus is a neighborhood in central Austin, Texas west of Guadalupe Street and its namesake, the University of Texas at Austin. Due to its proximity to the university, West Campus is heavily populated by college students.

Allandale, Austin, Texas is a neighborhood in North Central Austin, in the U.S. State of Texas known for its large lots, mature trees, and central location.

East César Chávez, historically and originally named Masontown or Masonville, is a neighborhood in Austin, Texas. It is located in the central-east part of Austin's urban core on the north bank of the Colorado River. The neighborhood encompasses much of ZIP code 78702.

Central East Austin is a neighborhood in Austin, Texas, United States. The neighborhood is bounded to the south by East 7th Street, to the west by Interstate 35, to the north by East Martin Luther King Jr Boulevard and to the east by Chicon Street, Rosewood Avenue and Northwestern Avenue.

Shoal Creek is a stream and an urban watershed in Austin, Texas, United States.

The history of African Americans in Austin dates back to 1839, when the first African American, Mahala Murchison, arrived. By the 1860s, several communities were established by freedmen that later became incorporated into the city proper. The relative share of Austin's African-American population has steadily declined since its peak in the late 20th century.

The West Sixth Street Bridge is a historic stone arch bridge in downtown Austin, Texas. Built in 1887, the bridge is one of the state's oldest masonry arch bridges. It is located at the site of the first bridge in Austin, carrying Sixth Street across Shoal Creek to link the western and central parts of the old city. The bridge was added to the National Register of Historic Places in 2014.

Wheatville was a historically black neighborhood in the city of Austin, Texas.

Roberts Clinic, a historic Colonial Revival building completed in 1937, was the first medical facility in Austin, Texas established to provide hospital rooms and care exclusively for the comfort of American Black patients. The practice offered treatment for acute and chronic illnesses, preventive treatment, minor surgeries, labor, delivery, and abortion services through the 1960s.

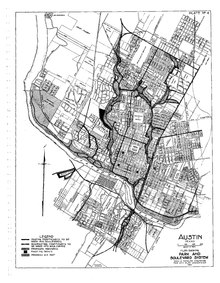

The West Fifth Street Bridge is a historic cantilever concrete girder bridge in downtown Austin, Texas. Built in 1931, the bridge carries Fifth Street across Shoal Creek to link central Austin with neighborhoods that were then the city's western suburbs. It is one of only a handful of curved cantilever girder bridges in Texas, built as part of the city's 1928 master plan for urban development and beautification. The bridge was added to the National Register of Historic Places in 2019.

The 1839 Austin city plan is the original city plan for the development of Austin, Texas, which established the grid plan for what is now downtown Austin. It was commissioned in 1839 by the government of the Republic of Texas and developed by Edwin Waller, a Texian revolutionary and politician who would later become Austin's first mayor.

The Third Street Railroad Trestle is a historic wooden railroad trestle bridge crossing Shoal Creek in downtown Austin, Texas. Built around 1922 by the International–Great Northern Railroad, it replaced an earlier bridge in the same place. The bridge was used by the I–GN Railroad, the Missouri Pacific Railroad, and the Missouri–Kansas–Texas Railroad until 1964, when commercial rail traffic stopped; after 1991 the bridge was abandoned. It was added to the National Register of Historic Places in 2021.

Anderson Stadium, also known as Yellow Jacket Stadium, is a historic football and track and field facility in East Austin, Texas. The stadium was built in 1953 as the football facility on what was then the campus of L.C. Anderson High School, Austin's only public high school open to African Americans under racial segregation. Closed in 1971 as part of a school integration plan and restored in the 1990s, Anderson Stadium was added to the National Register of Historic Places in 2022.

Waller Creek is a stream and an urban watershed in Austin, Texas, United States. Named after Edwin Waller, the first mayor of Austin, it has its headwaters near Highland Mall and runs in a southerly direction, through the University of Texas at Austin and the eastern part of downtown Austin, including the Red River Cultural District, to its end at Lady Bird Lake.