Defecation follows digestion, and is a necessary process by which organisms eliminate a solid, semisolid, or liquid waste material known as feces from the digestive tract via the anus or cloaca. The act has a variety of names ranging from the common, like pooping or crapping, to the technical, e.g. bowel movement, to the obscene (shitting), to the euphemistic, to the juvenile. The topic, usually avoided in polite company, can become the basis for some potty humor.

Constipation is a bowel dysfunction that makes bowel movements infrequent or hard to pass. The stool is often hard and dry. Other symptoms may include abdominal pain, bloating, and feeling as if one has not completely passed the bowel movement. Complications from constipation may include hemorrhoids, anal fissure or fecal impaction. The normal frequency of bowel movements in adults is between three per day and three per week. Babies often have three to four bowel movements per day while young children typically have two to three per day.

Fecal incontinence (FI), or in some forms, encopresis, is a lack of control over defecation, leading to involuntary loss of bowel contents, both liquid stool elements and mucus, or solid feces. When this loss includes flatus (gas), it is referred to as anal incontinence. FI is a sign or a symptom, not a diagnosis. Incontinence can result from different causes and might occur with either constipation or diarrhea. Continence is maintained by several interrelated factors, including the anal sampling mechanism, and incontinence usually results from a deficiency of multiple mechanisms. The most common causes are thought to be immediate or delayed damage from childbirth, complications from prior anorectal surgery, altered bowel habits. An estimated 2.2% of community-dwelling adults are affected. However, reported prevalence figures vary. A prevalence of 8.39% among non-institutionalized U.S adults between 2005 and 2010 has been reported, and among institutionalized elders figures come close to 50%.

Irritable bowel syndrome (IBS) is a functional gastrointestinal disorder characterized by a group of symptoms that commonly include abdominal pain, abdominal bloating and changes in the consistency of bowel movements. These symptoms may occur over a long time, sometimes for years. IBS can negatively affect quality of life and may result in missed school or work or reduced productivity at work. Disorders such as anxiety, major depression, and chronic fatigue syndrome are common among people with IBS.

A rectal prolapse occurs when walls of the rectum have prolapsed to such a degree that they protrude out of the anus and are visible outside the body. However, most researchers agree that there are 3 to 5 different types of rectal prolapse, depending on whether the prolapsed section is visible externally, and whether the full or only partial thickness of the rectal wall is involved.

Functional gastrointestinal disorders (FGID), also known as disorders of gut–brain interaction, include a number of separate idiopathic disorders which affect different parts of the gastrointestinal tract and involve visceral hypersensitivity and motility disturbances.

Functional constipation, known as chronic idiopathic constipation (CIC), is constipation that does not have a physical (anatomical) or physiological cause. It may have a neurological, psychological or psychosomatic cause. A person with functional constipation may be healthy, yet has difficulty defecating.

Rectal tenesmus is a feeling of incomplete defecation. It is the sensation of inability or difficulty to empty the bowel at defecation, even if the bowel contents have already been evacuated. Tenesmus indicates the feeling of a residue, and is not always correlated with the actual presence of residual fecal matter in the rectum. It is frequently painful and may be accompanied by involuntary straining and other gastrointestinal symptoms. Tenesmus has both a nociceptive and a neuropathic component.

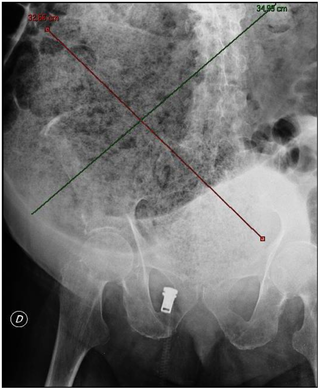

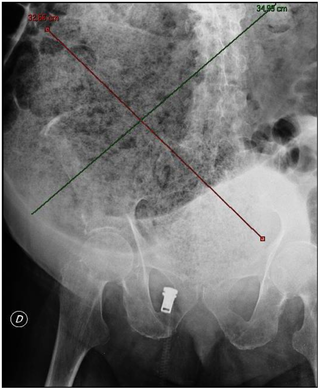

A fecal impaction or an impacted bowel is a solid, immobile bulk of feces that can develop in the rectum as a result of chronic constipation. Fecal impaction is a common result of neurogenic bowel dysfunction and causes immense discomfort and pain. Its treatment includes laxatives, enemas, and pulsed irrigation evacuation (PIE) as well as digital removal. It is not a condition that resolves without direct treatment.

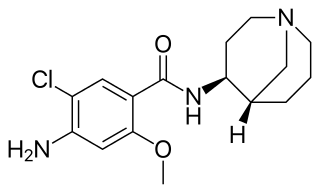

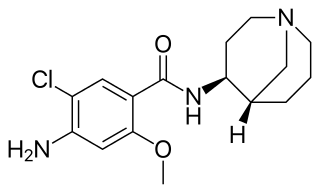

Renzapride is a prokinetic agent and antiemetic which acts as a full 5-HT4 agonist and partial 5-HT3 antagonist. It also functions as a 5-HT2B antagonist and has some affinity for the 5-HT2A and 5-HT2C receptors.

The Rome process and Rome criteria are an international effort to create scientific data to help in the diagnosis and treatment of functional gastrointestinal disorders, such as irritable bowel syndrome, functional dyspepsia and rumination syndrome. The Rome diagnostic criteria are set forth by Rome Foundation, a not for profit 501(c)(3) organization based in Raleigh, North Carolina, United States.

Lubiprostone, sold under the brand name Amitiza among others, is a medication used in the management of chronic idiopathic constipation, predominantly irritable bowel syndrome-associated constipation in women and opioid-induced constipation. The drug is owned by Mallinckrodt and is marketed by Takeda Pharmaceutical Company.

Human feces are the solid or semisolid remains of food that could not be digested or absorbed in the small intestine of humans, but has been further broken down by bacteria in the large intestine. It also contains bacteria and a relatively small amount of metabolic waste products such as bacterially altered bilirubin, and the dead epithelial cells from the lining of the gut. It is discharged through the anus during a process called defecation.

Bowel management is the process which a person with a bowel disability uses to manage fecal incontinence or constipation. People who have a medical condition which impairs control of their defecation use bowel management techniques to choose a predictable time and place to evacuate. A simple bowel management technique might include diet control and establishing a toilet routine. As a more involved practice a person might use an enema to relieve themselves. Without bowel management, the person might either suffer from the feeling of not getting relief, or they might soil themselves.

Bile acid malabsorption (BAM), known also as bile acid diarrhea, is a cause of several gut-related problems, the main one being chronic diarrhea. It has also been called bile acid-induced diarrhea, cholerheic or choleretic enteropathy, bile salt diarrhea or bile salt malabsorption. It can result from malabsorption secondary to gastrointestinal disease, or be a primary disorder, associated with excessive bile acid production. Treatment with bile acid sequestrants is often effective. It is recognised as a disability in the United Kingdom under the Equality Act 2010

Anismus or dyssynergic defecation is the failure of normal relaxation of pelvic floor muscles during attempted defecation. It can occur in both children and adults, and in both men and women. It can be caused by physical defects or it can occur for other reasons or unknown reasons. Anismus that has a behavioral cause could be viewed as having similarities with parcopresis, or psychogenic fecal retention.

Obstructed defecation syndrome is a major cause of functional constipation, of which it is considered a subtype. It is characterized by difficult and/or incomplete emptying of the rectum with or without an actual reduction in the number of bowel movements per week. Normal definitions of functional constipation include infrequent bowel movements and hard stools. In contrast, ODS may occur with frequent bowel movements and even with soft stools, and the colonic transit time may be normal, but delayed in the rectum and sigmoid colon.

Neurogenic bowel dysfunction (NBD) is the inability to control defecation due to a deterioration of or injury to the nervous system, resulting in faecal incontinence or constipation. It is common in people with spinal cord injury (SCI), multiple sclerosis (MS) or spina bifida.

Satish Sanku Chander Rao is the J.Harold Harrison Distinguished University Chair in Gastroenterology at the Medical College of Georgia, Augusta University. He served as the former President of the American Neurogastroenterology and Motility Society and as Chair of the American Gastroenterological Association (AGA) Institute Council, Neurogastroenterology/Motility Section.

Low anterior resection syndrome is a complication of lower anterior resection, a type of surgery performed to remove the rectum, typically for rectal cancer. It is characterized by changes to bowel function that affect quality of life, and includes symptoms such as fecal incontinence, incomplete defecation or the sensation of incomplete defecation, changes in stool frequency or consistency, unpredictable bowel function, and painful defecation (dyschezia). Treatment options include symptom management, such as use of enemas, or surgical management, such as creation of a colostomy.