Defecation follows digestion, and is a necessary process by which organisms eliminate a solid, semisolid, or liquid waste material known as feces from the digestive tract via the anus or cloaca. The act has a variety of names ranging from the common, like pooping or crapping, to the technical, e.g. bowel movement, to the obscene (shitting), to the euphemistic, to the juvenile. The topic, usually avoided in polite company, can become the basis for some potty humor.

Laxatives, purgatives, or aperients are substances that loosen stools and increase bowel movements. They are used to treat and prevent constipation.

Fecal incontinence (FI), or in some forms, encopresis, is a lack of control over defecation, leading to involuntary loss of bowel contents, both liquid stool elements and mucus, or solid feces. When this loss includes flatus (gas), it is referred to as anal incontinence. FI is a sign or a symptom, not a diagnosis. Incontinence can result from different causes and might occur with either constipation or diarrhea. Continence is maintained by several interrelated factors, including the anal sampling mechanism, and incontinence usually results from a deficiency of multiple mechanisms. The most common causes are thought to be immediate or delayed damage from childbirth, complications from prior anorectal surgery, altered bowel habits. An estimated 2.2% of community-dwelling adults are affected. However, reported prevalence figures vary. A prevalence of 8.39% among non-institutionalized U.S adults between 2005 and 2010 has been reported, and among institutionalized elders figures come close to 50%.

Irritable bowel syndrome (IBS) is a "disorder of gut-brain interaction" characterized by a group of symptoms that commonly include abdominal pain, abdominal bloating and changes in the consistency of bowel movements. These symptoms may occur over a long time, sometimes for years. IBS can negatively affect quality of life and may result in missed school or work or reduced productivity at work. Disorders such as anxiety, major depression, and chronic fatigue syndrome are common among people with IBS.

Hirschsprung's disease is a birth defect in which nerves are missing from parts of the intestine. The most prominent symptom is constipation. Other symptoms may include vomiting, abdominal pain, diarrhea and slow growth. Most children develop signs and symptoms shortly after birth. However, others may be diagnosed later in infancy or early childhood. About half of all children with Hirschsprung's disease are diagnosed in the first year of life. Complications may include enterocolitis, megacolon, bowel obstruction and intestinal perforation.

Encopresis is voluntary or involuntary passage of feces outside of toilet-trained contexts in children who are four years or older and after an organic cause has been excluded. Children with encopresis often leak stool into their undergarments.

A rectal prolapse occurs when walls of the rectum have prolapsed to such a degree that they protrude out of the anus and are visible outside the body. However, most researchers agree that there are 3 to 5 different types of rectal prolapse, depending on whether the prolapsed section is visible externally, and whether the full or only partial thickness of the rectal wall is involved.

Diverticulosis is the condition of having multiple pouches (diverticula) in the colon that are not inflamed. These are outpockets of the colonic mucosa and submucosa through weaknesses of muscle layers in the colon wall. Diverticula do not cause symptoms in most people. Diverticular disease occurs when diverticula become clinically inflamed, a condition known as diverticulitis.

Functional constipation, known as chronic idiopathic constipation (CIC), is constipation that does not have a physical (anatomical) or physiological cause. It may have a neurological, psychological or psychosomatic cause. A person with functional constipation may be healthy, yet has difficulty defecating.

A volvulus is when a loop of intestine twists around itself and the mesentery that supports it, resulting in a bowel obstruction. Symptoms include abdominal pain, abdominal bloating, vomiting, constipation, and bloody stool. Onset of symptoms may be rapid or more gradual. The mesentery may become so tightly twisted that blood flow to part of the intestine is cut off, resulting in ischemic bowel. In this situation there may be fever or significant pain when the abdomen is touched.

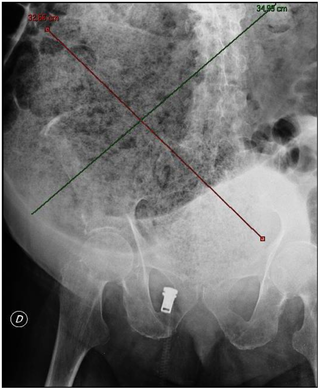

A fecal impaction or an impacted bowel is a solid, immobile bulk of feces that can develop in the rectum as a result of chronic constipation. Fecal impaction is a common result of neurogenic bowel dysfunction and causes immense discomfort and pain. Its treatment includes laxatives, enemas, and pulsed irrigation evacuation (PIE) as well as digital removal. It is not a condition that resolves without direct treatment.

Proctitis is an inflammation of the anus and the lining of the rectum, affecting only the last 6 inches of the rectum.

Abdominal bloating is a short-term disease that affects the gastrointestinal tract. Bloating is generally characterized by an excess buildup of gas, air or fluids in the stomach. A person may have feelings of tightness, pressure or fullness in the stomach; it may or may not be accompanied by a visibly distended abdomen. Bloating can affect anyone of any age range and is usually self-diagnosed, in most cases does not require serious medical attention or treatment. Although this term is usually used interchangeably with abdominal distension, these symptoms probably have different pathophysiological processes, which are not fully understood.

Blood in stool or rectal bleeding looks different depending on how early it enters the digestive tract—and thus how much digestive action it has been exposed to—and how much there is. The term can refer either to melena, with a black appearance, typically originating from upper gastrointestinal bleeding; or to hematochezia, with a red color, typically originating from lower gastrointestinal bleeding. Evaluation of the blood found in stool depends on its characteristics, in terms of color, quantity and other features, which can point to its source, however, more serious conditions can present with a mixed picture, or with the form of bleeding that is found in another section of the tract. The term "blood in stool" is usually only used to describe visible blood, and not fecal occult blood, which is found only after physical examination and chemical laboratory testing.

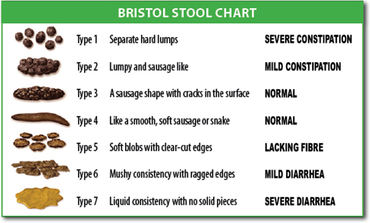

The Bristol stool scale is a diagnostic medical tool designed to classify the form of human faeces into seven categories. It is used in both clinical and experimental fields.

Human feces are the solid or semisolid remains of food that could not be digested or absorbed in the small intestine of humans, but has been further broken down by bacteria in the large intestine. It also contains bacteria and a relatively small amount of metabolic waste products such as bacterially altered bilirubin, and the dead epithelial cells from the lining of the gut. It is discharged through the anus during a process called defecation.

Solitary rectal ulcer syndrome or SRUS is a chronic, benign disorder of the rectal mucosa. It commonly occurs with varying degrees of rectal prolapse. The condition is thought to be caused by different factors, such as long term constipation, straining during defecation, and dyssynergic defecation. Treatment is by normalization of bowel habits, biofeedback, and other conservative measures. In more severe cases various surgical procedures may be indicated. The condition is relatively rare, affecting approximately 1 in 100,000 people per year. It affects mainly adults aged 30–50. Females are affected slightly more often than males. The disorder can be confused clinically with rectal cancer or other conditions such as inflammatory bowel disease, even when a biopsy is done.

Obstructed defecation syndrome is a major cause of functional constipation, of which it is considered a subtype. It is characterized by difficult and/or incomplete emptying of the rectum with or without an actual reduction in the number of bowel movements per week. Normal definitions of functional constipation include infrequent bowel movements and hard stools. In contrast, ODS may occur with frequent bowel movements and even with soft stools, and the colonic transit time may be normal, but delayed in the rectum and sigmoid colon.

Constipation in children refers to the medical condition of constipation in children. It is a functional gastrointestinal disorder.

Neurogenic bowel dysfunction (NBD) is the inability to control defecation due to a deterioration of or injury to the nervous system, resulting in faecal incontinence or constipation. It is common in people with spinal cord injury (SCI), multiple sclerosis (MS) or spina bifida.