Related Research Articles

Extended Binary Coded Decimal Interchange Code is an eight-bit character encoding used mainly on IBM mainframe and IBM midrange computer operating systems. It descended from the code used with punched cards and the corresponding six-bit binary-coded decimal code used with most of IBM's computer peripherals of the late 1950s and early 1960s. It is supported by various non-IBM platforms, such as Fujitsu-Siemens' BS2000/OSD, OS-IV, MSP, and MSP-EX, the SDS Sigma series, Unisys VS/9, Unisys MCP and ICL VME.

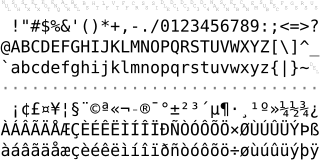

ISO/IEC 8859-1:1998, Information technology — 8-bit single-byte coded graphic character sets — Part 1: Latin alphabet No. 1, is part of the ISO/IEC 8859 series of ASCII-based standard character encodings, first edition published in 1987. ISO/IEC 8859-1 encodes what it refers to as "Latin alphabet no. 1", consisting of 191 characters from the Latin script. This character-encoding scheme is used throughout the Americas, Western Europe, Oceania, and much of Africa. It is the basis for some popular 8-bit character sets and the first two blocks of characters in Unicode.

ISO/IEC 8859-3:1999, Information technology — 8-bit single-byte coded graphic character sets — Part 3: Latin alphabet No. 3, is part of the ISO/IEC 8859 series of ASCII-based standard character encodings, first edition published in 1988. It is informally referred to as Latin-3 or South European. It was designed to cover Turkish, Maltese and Esperanto, though the introduction of ISO/IEC 8859-9 superseded it for Turkish. The encoding was popular for users of Esperanto, but fell out of use as application support for Unicode became more common.

ISO/IEC 646 is a set of ISO/IEC standards, described as Information technology — ISO 7-bit coded character set for information interchange and developed in cooperation with ASCII at least since 1964. Since its first edition in 1967 it has specified a 7-bit character code from which several national standards are derived.

ISO/IEC 8859-8, Information technology — 8-bit single-byte coded graphic character sets — Part 8: Latin/Hebrew alphabet, is part of the ISO/IEC 8859 series of ASCII-based standard character encodings. ISO/IEC 8859-8:1999 from 1999 represents its second and current revision, preceded by the first edition ISO/IEC 8859-8:1988 in 1988. It is informally referred to as Latin/Hebrew. ISO/IEC 8859-8 covers all the Hebrew letters, but no Hebrew vowel signs. IBM assigned code page 916 to it. This character set was also adopted by Israeli Standard SI1311:2002, with some extensions.

ISO/IEC 8859-4:1998, Information technology — 8-bit single-byte coded graphic character sets — Part 4: Latin alphabet No. 4, is part of the ISO/IEC 8859 series of ASCII-based standard character encodings, first edition published in 1988. It is informally referred to as Latin-4 or North European. It was designed to cover Estonian, Latvian, Lithuanian, Greenlandic, and Sámi. It has been largely superseded by ISO/IEC 8859-10 and Unicode. Microsoft has assigned code page 28594 a.k.a. Windows-28594 to ISO-8859-4 in Windows. IBM has assigned code page 914 to ISO 8859-4.

ISO/IEC 8859-5:1999, Information technology — 8-bit single-byte coded graphic character sets — Part 5: Latin/Cyrillic alphabet, is part of the ISO/IEC 8859 series of ASCII-based standard character encodings, first edition published in 1988. It is informally referred to as Latin/Cyrillic.

ISO/IEC 8859-6:1999, Information technology — 8-bit single-byte coded graphic character sets — Part 6: Latin/Arabic alphabet, is part of the ISO/IEC 8859 series of ASCII-based standard character encodings, first edition published in 1987. It is informally referred to as Latin/Arabic. It was designed to cover Arabic. Only nominal letters are encoded, no preshaped forms of the letters, so shaping processing is required for display. It does not include the extra letters needed to write most Arabic-script languages other than Arabic itself.

ISO/IEC 8859-10:1998, Information technology — 8-bit single-byte coded graphic character sets — Part 10: Latin alphabet No. 6, is part of the ISO/IEC 8859 series of ASCII-based standard character encodings, first edition published in 1992. It is informally referred to as Latin-6. It was designed to cover the Nordic languages, deemed of more use for them than ISO 8859-4.

ISO/IEC 8859-13:1998, Information technology — 8-bit single-byte coded graphic character sets — Part 13: Latin alphabet No. 7, is part of the ISO/IEC 8859 series of ASCII-based standard character encodings, first edition published in 1998. It is informally referred to as Latin-7 or Baltic Rim. It was designed to cover the Baltic languages, and added characters used in Polish missing from the earlier encodings ISO 8859-4 and ISO 8859-10. Unlike these two, it does not cover the Nordic languages. It is similar to the earlier-published Windows-1257; its encoding of the Estonian alphabet also matches IBM-922.

ISO/IEC 8859-14:1998, Information technology — 8-bit single-byte coded graphic character sets — Part 14: Latin alphabet No. 8 (Celtic), is part of the ISO/IEC 8859 series of ASCII-based standard character encodings, first edition published in 1998. It is informally referred to as Latin-8 or Celtic. It was designed to cover the Celtic languages, such as Irish, Manx, Scottish Gaelic, Welsh, Cornish, and Breton.

ISO/IEC 8859-16:2001, Information technology — 8-bit single-byte coded graphic character sets — Part 16: Latin alphabet No. 10, is part of the ISO/IEC 8859 series of ASCII-based standard character encodings, first edition published in 2001. The same encoding was defined as Romanian Standard SR 14111 in 1998, named the "Romanian Character Set for Information Interchange". It is informally referred to as Latin-10 or South-Eastern European. It was designed to cover Albanian, Croatian, Hungarian, Polish, Romanian, Serbian and Slovenian, but also French, German, Italian and Irish Gaelic.

ISO/IEC 2022Information technology—Character code structure and extension techniques, is an ISO/IEC standard in the field of character encoding. It is equivalent to the ECMA standard ECMA-35, the ANSI standard ANSI X3.41 and the Japanese Industrial Standard JIS X 0202. Originating in 1971, it was most recently revised in 1994.

T.61 is an ITU-T Recommendation for a Teletex character set. T.61 predated Unicode, and was the primary character set in ASN.1 used in early versions of X.500 and X.509 for encoding strings containing characters used in Western European languages. It is also used by older versions of LDAP. While T.61 continues to be supported in modern versions of X.500 and X.509, it has been deprecated in favor of Unicode. It is also called Code page 1036, CP1036, or IBM 01036.

Shift Out (SO) and Shift In (SI) are ASCII control characters 14 and 15, respectively. These are sometimes also called "Control-N" and "Control-O".

T.51 / ISO/IEC 6937:2001, Information technology — Coded graphic character set for text communication — Latin alphabet, is a multibyte extension of ASCII, or more precisely ISO/IEC 646-IRV. It was developed in common with ITU-T for telematic services under the name of T.51, and first became an ISO standard in 1983. Certain byte codes are used as lead bytes for letters with diacritics (accents). The value of the lead byte often indicates which diacritic that the letter has, and the follow byte then has the ASCII-value for the letter that the diacritic is on.

Many Unicode characters are used to control the interpretation or display of text, but these characters themselves have no visual or spatial representation. For example, the null character is used in C-programming application environments to indicate the end of a string of characters. In this way, these programs only require a single starting memory address for a string, since the string ends once the program reads the null character.

The MARC-8 charset is a MARC standard used in MARC-21 library records. The MARC formats are standards for the representation and communication of bibliographic and related information in machine-readable form, and they are frequently used in library database systems. The character encoding now known as MARC-8 was introduced in 1968 as part of the MARC format. Originally based on the Latin alphabet, from 1979 to 1983 the JACKPHY initiative expanded the repertoire to include Japanese, Arabic, Chinese, and Hebrew characters, with the later addition of Cyrillic and Greek scripts. If a character is not representable in MARC-8 of a MARC-21 record, then UTF-8 must be used instead. UTF-8 has support for many more characters than MARC-8, which is rarely used outside library data.

The ISO 2033:1983 standard defines character sets for use with Optical Character Recognition or Magnetic Ink Character Recognition systems. The Japanese standard JIS X 9010:1984 is closely related.

ISO/IEC 10367:1991 is a standard developed by ISO/IEC JTC 1/SC 2, defining graphical character sets for use in character encodings implementing levels 2 and 3 of ISO/IEC 4873.

References

- ↑ Fox, Brian. "Adding a new node to Info". Info: The online, menu-driven GNU documentation system. GNU Project.

- ↑ "Built-in Types § str.splitlines". The Python Standard Library. Python Software Foundation.

- 1 2 ISO/TC 97/SC 2 (1975). The set of control characters of the ISO 646 (PDF). ITSCJ/IPSJ. ISO-IR-1.

{{citation}}: CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - 1 2 3 IPTC (1995). The IPTC Recommended Message Format (PDF) (5th ed.). IPTC TEC 7901.

- 1 2 3 "end-of-transmission character (EOT)". Federal Standard 1037C . 1996. Archived from the original on 2016-03-09.

- 1 2 Robert McConnell; James Haynes; Richard Warren (December 2002). "Understanding ASCII Codes". NADCOMM.

- ↑ Williamson, Karl. "Re: PRI #202: Extensions to NameAliases.txt for Unicode 6.1.0".

- 1 2 3 Ken Whistler (July 20, 2011). "Formal Name Aliases for Control Characters, L2/11-281". Unicode Consortium.

- 1 2 3 4 "Name Aliases". Unicode Character Database. Unicode Consortium.

- ↑ "C0 Controls and Basic Latin" (PDF). Unicode Consortium.

- ↑ "charnames". Perl Programming Documentation.

- ↑ ECMA (1994). "7.3: Invocation of character-set code elements". Character Code Structure and Extension Techniques (PDF) (ECMA Standard) (6th ed.). p. 14. ECMA-35.

- ↑ American Standards Association (1963). American Standard Code for Information Interchange: 4. Legend. p. 6. ASA X3.4-1963.

- ↑ "data link escape character (DLE)". Federal Standard 1037C . 1996. Archived from the original on 2016-08-01.

- ↑ "Supplementary transmission control functions (an extension of the basic mode control procedures for data communication systems)". European Computer Manufacturers Association. 1972. ECMA-37.

- ↑ "What is the point of Ctrl-S?". Unix and Linux Stack exchange. Retrieved 14 February 2019.

- ↑ ECMA/TC 1 (1973). "Brief History". 7-bit Input/Output Coded Character Set (PDF) (4th ed.). ECMA. ECMA-6:1973.

{{citation}}: CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - 1 2 3 ECMA/TC 1 (1971). "8.2: Correspondence between the 7-bit Code and an 8-bit Code". Extension of the 7-bit Coded Character Set (PDF) (1st ed.). ECMA. pp. 21–24. ECMA-35:1971.

{{citation}}: CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - ↑ ECMA/TC 1 (1973). "4.2: Specific Control Characters". 7-bit Input/Output Coded Character Set (PDF) (4th ed.). ECMA. p. 16. ECMA-6:1973.

{{citation}}: CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - ↑ ECMA/TC 1 (1985). "5.3.8: Sets of 96 graphic characters". Code Extension Techniques (PDF) (4th ed.). ECMA. pp. 17–18. ECMA-35:1985.

{{citation}}: CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - 1 2 3 ISO/IEC International Register of Coded Character Sets To Be Used With Escape Sequences (PDF), ITSCJ/IPSJ, ISO-IR

- 1 2 DIN (1979-07-15). Additional Control Codes for Bibliographic Use according to German Standard DIN 31626 (PDF). ITSCJ/IPSJ. ISO-IR-40.

- 1 2 3 ISO/TC97/SC2 (1983-10-01). C1 Control Set of ISO 6429:1983 (PDF). ITSCJ/IPSJ. ISO-IR-77.

{{citation}}: CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - ↑ ECMA/TC 1 (1979). "Brief History". Additional Control Functions for Character-Imaging I/O Devices (PDF) (2nd ed.). ECMA. ECMA-48:1979.

{{citation}}: CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - ↑ "JIS X 02xx 符号" (in Japanese).

- 1 2 Ken Whistler (2015-10-05). "Why Nothing Ever Goes Away". Unicode Mailing List.

- ↑ ECMA/TC 1 (June 1991). Control Functions for Coded Character Sets (PDF) (5th ed.). ECMA. ECMA-48:1991.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - 1 2 ISO 6429:1983 Information processing — ISO 7-bit and 8-bit coded character sets — Additional control functions for character-imaging devices. ISO. 1983-05-01.

- ↑ ISO 6429:1988 Information processing — Control functions for 7-bit and 8-bit coded character sets. ISO. 1988-11-15.

- 1 2 ISO/IEC 6429:1992 Information technology — Control functions for coded character sets. ISO. 1992-12-15. Retrieved 2024-05-29.

- ↑ Lunde, Ken (2008). CJKV Information Processing: Chinese, Japanese, Korean, and Vietnamese Computing. O'Reilly. p. 244. ISBN 9780596800925.

- ↑ ECMA/TC 1 (December 1986). "Appendix E: Changes Made in this Edition". Control Functions for Coded Character Sets (PDF) (4th ed.). ECMA. ECMA-48:1986.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - ↑ ECMA/TC 1 (June 1991). "F.8 Eliminated control functions". Control Functions for Coded Character Sets (PDF) (5th ed.). ECMA. ECMA-48:1991.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - ↑ "VT100 Widget Resources (§ hpLowerleftBugCompat)". xterm - terminal emulator for X.

- ↑ Moy, Edward; Gildea, Stephen; Dickey, Thomas. "Device-Control functions". XTerm Control Sequences.

- 1 2 Brender, Ronald F. (1989). "Ada 9x Project Report: Character Set Issues for Ada 9x". Carnegie Mellon University.

- ↑ Moy, Edward; Gildea, Stephen; Dickey, Thomas. "Operating System Commands". XTerm Control Sequences.

- ↑ Frank da Cruz; Christine Gianone (1997). Using C-Kermit. Digital Press. p. 278. ISBN 978-1-55558-164-0.

- 1 2 3 ECMA (1994). "6.4.2: Primary sets of coded control functions". Character Code Structure and Extension Techniques (PDF) (ECMA Standard) (6th ed.). p. 11. ECMA-35.

- ↑ ISO/TC97/SC2/WG-7; ECMA (1985-08-01). Minimum C0 set for ISO 4873 (PDF). ITSCJ/IPSJ. ISO-IR-104.

{{citation}}: CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - ↑ ISO/TC97/SC2/WG-7; ECMA (1985-08-01). Minimum C1 Set for ISO 4873 (PDF). ITSCJ/IPSJ. ISO-IR-105.

{{citation}}: CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - ↑ ECMA (1994). "6.2: Fixed coded characters". Character Code Structure and Extension Techniques (PDF) (ECMA Standard) (6th ed.). p. 7. ECMA-35.

- ↑ ECMA (1994). "6.4.3: Supplementary sets of coded control functions". Character Code Structure and Extension Techniques (PDF) (ECMA Standard) (6th ed.). p. 11. ECMA-35.

- ↑ ITU (1985). Teletex Primary Set of Control Functions (PDF). ITSCJ/IPSJ. ISO-IR-106.

- ↑ Úřad pro normalizaci a měřeni (1987). The set of control characters of ISO 646, with EM replaced by SS2 (PDF). ITSCJ/IPSJ. ISO-IR-140.

- ↑ ISO/TC 97/SC 2 (1977). The set of control characters of ISO 646, with IS4 replaced by Single Shift for G2 (SS2) (PDF). ITSCJ/IPSJ. ISO-IR-36.

{{citation}}: CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - 1 2 ISO/TC97/SC2/WG6. "Liaison statement to ISO/TC97/SC2/WG8 and ISO/TC97/SC18/WG8" (PDF). ISO/TC97/SC2/WG6 N317.rev. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2020-10-26.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - ↑ ISO/TC 97/SC 2 (1982). The C0 set of Control Characters of Japanese Standard JIS C 6225-1979 (PDF). ITSCJ/IPSJ. ISO-IR-74.

{{citation}}: CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - ↑ Printronix (2012). OKI® Programmer's Reference Manual (PDF). p. 26.

- ↑ ISO/TC 46 (1983-06-01). Additional Control Codes for Bibliographic Use according to International Standard ISO 6630 (PDF). ITSCJ/IPSJ. ISO-IR-67.

{{citation}}: CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - ↑ ISO/TC 46 (1986-02-01). Additional Control Codes for Bibliographic Use according to International Standard ISO 6630 (PDF). ITSCJ/IPSJ. ISO-IR-124.

{{citation}}: CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - 1 2 Umamaheswaran, V.S. (1999-11-08). "3.3 Step 2: Byte Conversion". UTF-EBCDIC. Unicode Consortium. Unicode Technical Report #16.

The 64 control characters […], the ASCII DELETE character (U+007F)[…] are mapped respecting EBCDIC conventions, as defined in IBM Character Data Representation Architecture, CDRA, with one exception -- the pairing of EBCDIC Line Feed and New Line control characters are swapped from their CDRA default pairings to ISO/IEC 6429 Line Feed (U+000A) and Next Line (U+0085) control characters

- ↑ Steele, Shawn (1996-04-24). cp037_IBMUSCanada to Unicode table. Microsoft/Unicode Consortium.

- 1 2 "23.1: Control Codes" (PDF). The Unicode Standard (15.0.0 ed.). Unicode Consortium. 2022. pp. 914–916. ISBN 978-1-936213-32-0.

- The Unicode Standard

- C0 Controls and Basic Latin

- C1 Controls and Latin-1 Supplement

- Control Pictures

- The Unicode Standard, Version 6.1.0, Chapter 16: Special Areas and Format Characters

- ATIS Telecom Glossary 2007

- De litteris regentibus C1 quaestiones septem or Are C1 characters legal in XHTML 1.0?

- W3C I18N FAQ: HTML, XHTML, XML and Control Codes

- International register of coded character sets to be used with escape sequences