The Tetrarchy was the system instituted by Roman emperor Diocletian in 293 AD to govern the ancient Roman Empire by dividing it between two emperors, the augusti, and their junior colleagues and designated successors, the caesares.

The 300s decade ran from January 1, 300, to December 31, 309.

The Circus Maximus is an ancient Roman chariot-racing stadium and mass entertainment venue in Rome, Italy. In the valley between the Aventine and Palatine hills, it was the first and largest stadium in ancient Rome and its later Empire. It measured 621 m (2,037 ft) in length and 118 m (387 ft) in width and could accommodate over 150,000 spectators. In its fully developed form, it became the model for circuses throughout the Roman Empire. The site is now a public park.

Year 306 (CCCVI) was a common year starting on Tuesday of the Julian calendar. At the time, it was known as the Year of the Consulship of Constantius and Valerius. The denomination 306 for this year has been used since the early medieval period, when the Anno Domini calendar era became the prevalent method in Europe for naming years.

Galerius Valerius Maximianus was Roman emperor from 305 to 311. During his reign he campaigned, aided by Diocletian, against the Sasanian Empire, sacking their capital Ctesiphon in 299. He also campaigned across the Danube against the Carpi, defeating them in 297 and 300. Although he was a staunch opponent of Christianity, Galerius ended the Diocletianic Persecution when he issued the Edict of Toleration in Serdica (Sofia) in 311.

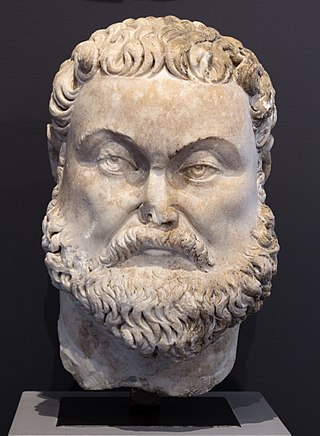

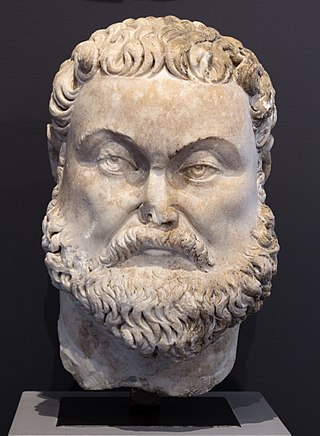

Maximian, nicknamed Herculius, was Roman emperor from 286 to 305. He was Caesar from 285 to 286, then Augustus from 286 to 305. He shared the latter title with his co-emperor and superior, Diocletian, whose political brain complemented Maximian's military brawn. Maximian established his residence at Trier but spent most of his time on campaign. In late 285, he suppressed rebels in Gaul known as the Bagaudae. From 285 to 288, he fought against Germanic tribes along the Rhine frontier. Together with Diocletian, he launched a scorched earth campaign deep into Alamannic territory in 288, refortifying the frontier.

Marcus Aurelius Valerius Maxentius was a Roman emperor from 306 until his death in 312. Despite ruling in Italy and North Africa, and having the recognition of the Senate in Rome, he was not recognized as a legitimate emperor by his fellow emperors.

Flavius Valerius Severus, also called Severus II, was a Roman emperor from 306 to 307. After failing to besiege Rome, he fled to Ravenna. It is thought that he was killed there or executed near Rome.

Piazza Navona is a public open space in Rome, Italy. It is built on the site of the 1st century AD Stadium of Domitian and follows the form of the open space of the stadium in an elongated oval. The ancient Romans went there to watch the agones ("games"), and hence it was known as "Circus Agonalis". It is believed that over time the name changed to in avone to navone and eventually to navona.

The pyramid of Cestius is a Roman Era pyramid in Rome, Italy, near the Porta San Paolo and the Protestant Cemetery. It was built as a tomb for Gaius Cestius, a member of the Epulones religious corporation. It stands at a fork between two ancient roads, the Via Ostiensis and another road that ran west to the Tiber along the approximate line of the modern Via Marmorata. Due to its incorporation into the city's fortifications, it is today one of the best-preserved ancient buildings in Rome.

(Marcus Aurelius) Valerius Romulus, was the son of Emperor Maxentius and of Valeria Maximilla, daughter of Emperor Galerius by his first wife. Through his father, he was also grandson of Maximian the Tetrarch, whom he predeceased.

Fontana dei Quattro Fiumi is a fountain in the Piazza Navona in Rome, Italy. It was designed in 1651 by Gian Lorenzo Bernini for Pope Innocent X whose family palace, the Palazzo Pamphili, faced onto the piazza as did the church of Sant'Agnese in Agone of which Innocent was the sponsor.

The Mausoleum of Maxentius was part of a large complex on the Appian Way in Rome that included a palace and a chariot racing circus, constructed by the Emperor Maxentius. The large circular tomb was built by Maxentius in the early 4th century, probably with himself in mind and as a family tomb, but when his young son Valerius Romulus died he was buried there. After extensive renovation the mausoleum was reopened to the public in 2014.

The Domus Severiana is the modern name given to the final extension to the imperial palaces on the Palatine Hill in Rome, built to the south-east of the Stadium Palatinum in the Domus Augustana of Septimius Severus. It included the Baths of Septimius Severus.

The following outline is provided as an overview of and topical guide to Rome:

The Atrium Libertatis was a monument of ancient Rome, the seat of the censors' archive, located on the saddle that connected the Capitolium to the Quirinal Hill, a short distance from the Roman Forum.

The Villa of Maxentius is an imperial villa in Rome, built by the Roman emperor Maxentius. The complex is located between the second and third miles of the ancient Appian Way, and consists of three main buildings: the palace, the circus of Maxentius and the dynastic mausoleum, designed in an inseparable architectural unit to honor Maxentius.

Appio-Latino is the 9th quartiere of Rome (Italy), identified by the initials Q. IX. The name derives from the ancient roads Via Appia and Via Latina. It belongs to the Municipio VII and Municipio VIII.