The stomach is a muscular, hollow organ in the upper gastrointestinal tract of humans and many other animals, including several invertebrates. The stomach has a dilated structure and functions as a vital organ in the digestive system. The stomach is involved in the gastric phase of digestion, following the cephalic phase in which the sight and smell of food and the act of chewing are stimuli. In the stomach a chemical breakdown of food takes place by means of secreted digestive enzymes and gastric acid.

The gastrointestinal tract is the tract or passageway of the digestive system that leads from the mouth to the anus. The GI tract contains all the major organs of the digestive system, in humans and other animals, including the esophagus, stomach, and intestines. Food taken in through the mouth is digested to extract nutrients and absorb energy, and the waste expelled at the anus as faeces. Gastrointestinal is an adjective meaning of or pertaining to the stomach and intestines.

In physiology, dehydration is a lack of total body water, with an accompanying disruption of metabolic processes. It occurs when free water loss exceeds free water intake, usually due to exercise, disease, or high environmental temperature. Mild dehydration can also be caused by immersion diuresis, which may increase risk of decompression sickness in divers.

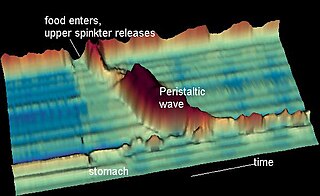

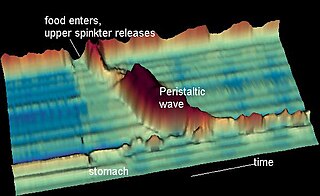

Peristalsis is a type of intestinal motility, characterized by radially symmetrical contraction and relaxation of muscles that propagate in a wave down a tube, in an anterograde direction. Peristalsis is progression of coordinated contraction of involuntary circular muscles, which is preceded by a simultaneous contraction of the longitudinal muscle and relaxation of the circular muscle in the lining of the gut.

Digestion is the breakdown of large insoluble food compounds into small water-soluble components so that they can be absorbed into the blood plasma. In certain organisms, these smaller substances are absorbed through the small intestine into the blood stream. Digestion is a form of catabolism that is often divided into two processes based on how food is broken down: mechanical and chemical digestion. The term mechanical digestion refers to the physical breakdown of large pieces of food into smaller pieces which can subsequently be accessed by digestive enzymes. Mechanical digestion takes place in the mouth through mastication and in the small intestine through segmentation contractions. In chemical digestion, enzymes break down food into the small compounds that the body can use.

The esophagus or oesophagus, colloquially known also as the food pipe, food tube, or gullet, is an organ in vertebrates through which food passes, aided by peristaltic contractions, from the pharynx to the stomach. The esophagus is a fibromuscular tube, about 25 cm (10 in) long in adults, that travels behind the trachea and heart, passes through the diaphragm, and empties into the uppermost region of the stomach. During swallowing, the epiglottis tilts backwards to prevent food from going down the larynx and lungs. The word oesophagus is from Ancient Greek οἰσοφάγος (oisophágos), from οἴσω (oísō), future form of φέρω + ἔφαγον.

Swallowing, also called deglutition or inglutition in scientific contexts, is the process in the body of a human or other animal that allows for a substance to pass from the mouth, to the pharynx, and into the esophagus, while shutting the epiglottis. Swallowing is an important part of eating and drinking. If the process fails and the material goes through the trachea, then choking or pulmonary aspiration can occur. In the human body the automatic temporary closing of the epiglottis is controlled by the swallowing reflex.

Eating is the ingestion of food. In biology, this is typically done to provide a heterotrophic organism with energy and nutrients and to allow for growth. Animals and other heterotrophs must eat in order to survive — carnivores eat other animals, herbivores eat plants, omnivores consume a mixture of both plant and animal matter, and detritivores eat detritus. Fungi digest organic matter outside their bodies as opposed to animals that digest their food inside their bodies.

Thirst is the craving for potable fluids, resulting in the basic instinct of animals to drink. It is an essential mechanism involved in fluid balance. It arises from a lack of fluids or an increase in the concentration of certain osmolites, such as sodium. If the water volume of the body falls below a certain threshold or the osmolite concentration becomes too high, structures in the brain detect changes in blood constituents and signal thirst.

Chewing or mastication is the process by which food is crushed and ground by the teeth. It is the first step in the process of digestion, allowing a greater surface area for digestive enzymes to break down the foods.

Licking is the action of passing the tongue over a surface, typically either to deposit saliva onto the surface, or to collect liquid, food or minerals onto the tongue for ingestion, or to communicate with other animals. Many animals both groom themselves, eat or drink by licking.

Cud is a portion of food that returns from a ruminant's stomach to the mouth to be chewed for the second time. More precisely, it is a bolus of semi-degraded food regurgitated from the reticulorumen of a ruminant. Cud is produced during the physical digestive process of rumination.

A beer bong is a device composed of a funnel attached to a tube used to facilitate the rapid consumption of beer. The use of a beer bong is also known as funneling.

Megaesophagus, also known as esophageal dilatation, is a disorder of the esophagus in humans and other mammals, whereby the esophagus becomes abnormally enlarged. Megaesophagus may be caused by any disease which causes the muscles of the esophagus to fail to properly propel food and liquid from the mouth into the stomach. Food can become lodged in the flaccid esophagus, where it may decay, be regurgitated, or maybe inhaled into the lungs.

Cat anatomy comprises the anatomical studies of the visible parts of the body of a domestic cat, which are similar to those of other members of the genus Felis.

Fluid balance is an aspect of the homeostasis of organisms in which the amount of water in the organism needs to be controlled, via osmoregulation and behavior, such that the concentrations of electrolytes in the various body fluids are kept within healthy ranges. The core principle of fluid balance is that the amount of water lost from the body must equal the amount of water taken in; for example, in humans, the output must equal the input. Euvolemia is the state of normal body fluid volume, including blood volume, interstitial fluid volume, and intracellular fluid volume; hypovolemia and hypervolemia are imbalances. Water is necessary for all life on Earth. Humans can survive for 4 to 6 weeks without food but only for a few days without water.

The relationship between alcohol consumption and body weight is the subject of inconclusive studies. Findings of these studies range from increase in body weight to a small decrease among women who begin consuming alcohol. Some of these studies are conducted with numerous subjects; one involved nearly 8,000 and another 140,000 subjects.

Polydipsia is an excessively large water intake. Its occurrence in captive birds has been recorded, although it is a relatively rare abnormal behaviour.

The human digestive system consists of the gastrointestinal tract plus the accessory organs of digestion. Digestion involves the breakdown of food into smaller and smaller components, until they can be absorbed and assimilated into the body. The process of digestion has three stages: the cephalic phase, the gastric phase, and the intestinal phase.

The rock dove, Columbia livia, has a number of special adaptations for regulating water uptake and loss.