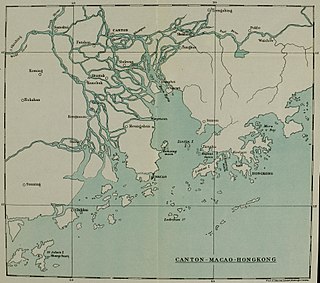

The First Opium War, also known as the Anglo-Chinese War, was a series of military engagements fought between the British Empire and the Qing dynasty of China between 1839 and 1842. The immediate issue was the Chinese enforcement of their ban on the opium trade by seizing private opium stocks from merchants at Canton and threatening to impose the death penalty for future offenders. Despite the opium ban, the British government supported the merchants' demand for compensation for seized goods, and insisted on the principles of free trade and equal diplomatic recognition with China. Opium was Britain's single most profitable commodity trade of the 19th century. After months of tensions between the two states, the British navy launched an expedition in June 1840, which ultimately defeated the Chinese using technologically superior ships and weapons by August 1842. The British then imposed the Treaty of Nanking, which forced China to increase foreign trade, give compensation, and cede Hong Kong Island to the British. Consequently the opium trade continued in China. Twentieth-century nationalists considered 1839 the start of a century of humiliation, and many historians consider it the beginning of modern Chinese history.

The Second Opium War, also known as the Second Anglo-Sino War, the Second China War, the Arrow War, or the Anglo-French expedition to China, was a colonial war lasting from 1856 to 1860, which pitted the British Empire and the French Empire against the Qing dynasty of China.

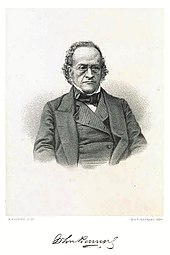

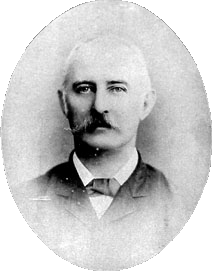

Sir John Bowring, or Phraya Siamanukulkij Siammitrmahayot was a British political economist, traveller, writer, literary translator, polyglot and the fourth Governor of Hong Kong. He was appointed by Queen Victoria as emissary to Siam, later he was appointed by King Mongkut of Siam as ambassador to London, also making a treaty of amity with Siam on April 18, 1855, now referred to as the "Bowring Treaty". His namesake treaty was fully effective for 70 years, until the reign of Vajiravudh. This treaty was gradually edited and became completely ineffective in 1938 under the government of Plaek Phibunsongkhram. Later, he was sent as a commissioner of Britain to the newly created Kingdom of Italy in 1861. He died in Claremont in Devon on 23 November 1872.

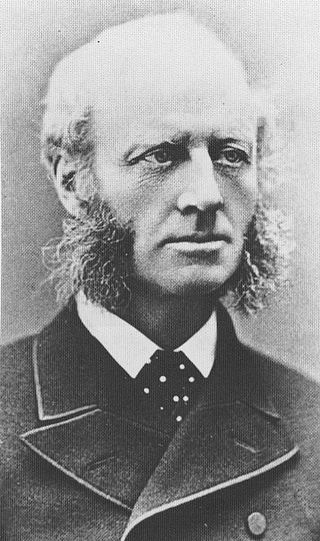

Sir Harry Smith Parkes was a British diplomat who served as Envoy Extraordinary and Minister Plenipotentiary and Consul General of the United Kingdom to the Empire of Japan from 1865 to 1883 and the Chinese Qing Empire from 1883 to 1885, and Minister to Korea in 1884. Parkes Street in Kowloon, Hong Kong is named after him.

Lieutenant-General Sir Henry Pottinger, 1st Baronet, was an Anglo-Irish soldier and colonial administrator who became the first Governor of Hong Kong.

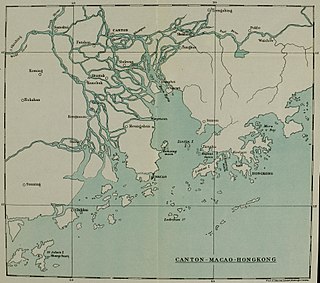

Hong Kong (1800s–1930s) oversaw the founding of the new crown colony of Hong Kong under the British Empire. After the First Opium War, the territory was ceded by the Qing Empire to the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland through Treaty of Nanjing (1842) and Convention of Peking (1860) in perpetuity, with additional land was leased to the British under the Convention for the Extension of Hong Kong Territory (1898), Hong Kong became one of the first parts of East Asia to undergo industrialisation.

The Convention between the United Kingdom and China, Respecting an Extension of Hong Kong Territory, commonly known as the Convention for the Extension of Hong Kong Territory or the Second Convention of Peking, was a lease signed between Qing China and the United Kingdom in Peking on 9 June 1898, leasing to the United Kingdom for 99 years, at no charge, the New Territories and northern Kowloon, including 235 islands.

A hong was a type of Chinese merchant establishment and its associated type of building. Hongs arose in Guangzhou as intermediaries between Western and Chinese merchants during the 18–19th century, under the Canton System.

Ye Mingchen was a high-ranking Chinese official during the Qing dynasty, known for his resistance to British influence in Canton (Guangzhou) in the aftermath of the First Opium War and his role in the beginning of the Second Opium War.

The Canton–Hong Kong strike was a strike and boycott that took place in British Hong Kong and Guangzhou (Canton), Republic of China, from June 1925 to October 1926. It started out as a response to the May 30 Movement shooting incidents in which Chinese protesters were fired upon by Sikh detachments of the Shanghai Municipal Police in Shanghai.

Hong Kong was a colony of the British Empire and later a dependent territory of the United Kingdom from 1841 to 1997, apart from a period of Japanese occupation from 1941 to 1945 during the Pacific War. The colonial period began with the British occupation of Hong Kong Island in 1841, during the First Opium War between the British and the Qing dynasty. The Qing had wanted to enforce its prohibition of opium importation within the dynasty that was being exported mostly from British India and was causing widespread addiction among the populace.

John Walter Hulme was a British lawyer and Judge. He was the first Chief Justice of Hong Kong, taking office in 1844.

Catherine Ann Janvier was an American artist, author, and translator. Before she married, she had an established career as an artist and teacher under the name Catherine Ann Drinker.

Daniel Richard Francis Caldwell was a colonial government official in Hong Kong. He was Registrar General and Protector of Chinese from 1856 to 1862 and was involved in the notorious Caldwell Affair in the late 1850s.

Cumsingmoon or Jinxingmen is an anchorage in Zhuhai, Guangdong, on the southern coast of China, within the Pearl River estuary and close to the former European colonies of Macao and Hong Kong.

William Thomas Bridges was a lawyer and public servant in British Hong Kong, where he held the post of Acting Colonial Secretary from 1857 to 1858. He was born in 1820 or 1821 in Blackheath, Kent. Having studied at Winchester College and Corpus Christi College, Oxford, Bridges was called to the Bar at the Middle Temple in 1847. He emigrated to Hong Kong in April 1851 and rose rapidly in local society owing to his special status as a qualified barrister in a colony short of legal experts, becoming Acting Attorney General within a year of his arrival. After a sojourn in England in 1856, where he was awarded an honorary Doctorate of Civil Law, Bridges became a provisional member of the Executive and Legislative Councils upon his return to Hong Kong, and was appointed Acting Colonial Secretary while the incumbent secretary, William Thomas Mercer, was on leave in 1857.

William Tarrant was a civil servant and newspaper editor in British Hong Kong. He served as Inspector of Land and Roads and subsequently Registrar of Deeds in the Hong Kong colonial administration from 1842 to 1847, but was removed from office and barred from public service owing to allegations he had raised against Colonial Secretary William Caine, which an internal government inquiry held to be fabricated. Tarrant then began a new career in journalism, purchasing the Friend of China newspaper in 1850. He became prominently involved in a scandal involving multiple senior government officers, the Caldwell affair, in 1857, and was ultimately found guilty of libel and imprisoned in 1859. He left the colony after his release in 1860, and made two attempts over the course of the 1860s to restart the Friend of China in Guangzhou and Shanghai, each proving abortive. Finally, he sold the paper in 1869 and retired to England, where he died in 1872.

Lowe Kong Meng was a Chinese-Australian businessman. Born into a trading family in Penang, Kong Meng learned English and French at an early age and worked as an importing merchant around the Indian Ocean. In 1853 he moved to Melbourne where he started a business importing goods for Chinese miners during the Victorian gold rush. After 1860, as the Chinese population in Melbourne peaked, he diversified into other lines of business, including investing in the Commercial Bank of Australia. Kong Meng was a prominent and well-regarded member of Melbourne's elite, and for a time was one of the city's wealthiest men. He was a leading defender of Chinese Australians at a time when their status was politically controversial and they were subjected to targeted taxation, discrimination and violence.

Cheok Hong Cheong, also known as Zhang Zhuoxiong, was a Chinese-born Australian missionary, political activist, writer, and businessman. Originally a Presbyterian elder, he became the superintendent of the Anglican mission in Melbourne. A staunch campaigner against anti-Chinese sentiment in Australia, he co-authored a booklet titled The Chinese Question in Australia (1879) with Lowe Kong Meng and Louis Ah Mouy. He was also opposed to the British opium trade.