Ascaris lumbricoides is a large parasitic worm that causes ascariasis in humans. A roundworm of genus Ascaris, it is the most common parasitic worm in humans. An estimated 807 million–1.2 billion people are infected with A. lumbricoides worldwide. People living in tropical and subtropical countries are at greater risk of infection.

Strongyloides stercoralis is a human pathogenic parasitic roundworm causing the disease strongyloidiasis. Its common name in the US is threadworm. In the UK and Australia, however, the term threadworm can also refer to nematodes of the genus Enterobius, otherwise known as pinworms.

Trichuriasis, also known as whipworm infection, is an infection by the parasitic worm Trichuris trichiura (whipworm). If infection is only with a few worms, there are often no symptoms. In those who are infected with many worms, there may be abdominal pain, fatigue and diarrhea. The diarrhea sometimes contains blood. Infections in children may cause poor intellectual and physical development. Low red blood cell levels may occur due to loss of blood.

Ascariasis is a disease caused by the parasitic roundworm Ascaris lumbricoides. Infections have no symptoms in more than 85% of cases, especially if the number of worms is small. Symptoms increase with the number of worms present and may include shortness of breath and fever in the beginning of the disease. These may be followed by symptoms of abdominal swelling, abdominal pain, and diarrhea. Children are most commonly affected, and in this age group the infection may also cause poor weight gain, malnutrition, and learning problems.

Helminthiasis, also known as worm infection, is any macroparasitic disease of humans and other animals in which a part of the body is infected with parasitic worms, known as helminths. There are numerous species of these parasites, which are broadly classified into tapeworms, flukes, and roundworms. They often live in the gastrointestinal tract of their hosts, but they may also burrow into other organs, where they induce physiological damage.

Hookworm infection is an infection by a type of intestinal parasite known as a hookworm. Initially, itching and a rash may occur at the site of infection. Those only affected by a few worms may show no symptoms. Those infected by many worms may experience abdominal pain, diarrhea, weight loss, and tiredness. The mental and physical development of children may be affected. Anemia may result.

Necator americanus is a species of hookworm commonly known as the New World hookworm. Like other hookworms, it is a member of the phylum Nematoda. It is an obligatory parasitic nematode that lives in the small intestine of human hosts. Necatoriasis—a type of helminthiasis—is the term for the condition of being host to an infestation of a species of Necator. Since N. americanus and Ancylostoma duodenale are the two species of hookworms that most commonly infest humans, they are usually dealt with under the collective heading of "hookworm infection". They differ most obviously in geographical distribution, structure of mouthparts, and relative size.

Parasitic worms, also known as helminths, are large macroparasites; adults can generally be seen with the naked eye. Many are intestinal worms that are soil-transmitted and infect the gastrointestinal tract. Other parasitic worms such as schistosomes reside in blood vessels.

Helminthic therapy, an experimental type of immunotherapy, is the treatment of autoimmune diseases and immune disorders by means of deliberate infestation with a helminth or with the eggs of a helminth. Helminths are parasitic worms such as hookworms, whipworms, and threadworms that have evolved to live within a host organism on which they rely for nutrients. These worms are members of two phyla: nematodes, which are primarily used in human helminthic therapy, and flat worms (trematodes).

Neglected tropical diseases (NTDs) are a diverse group of tropical infections that are common in low-income populations in developing regions of Africa, Asia, and the Americas. They are caused by a variety of pathogens, such as viruses, bacteria, protozoa, and parasitic worms (helminths). These diseases are contrasted with the "big three" infectious diseases, which generally receive greater treatment and research funding. In sub-Saharan Africa, the effect of neglected tropical diseases as a group is comparable to that of malaria and tuberculosis. NTD co-infection can also make HIV/AIDS and tuberculosis more deadly.

Deworming is the giving of an anthelmintic drug to a human or animals to rid them of helminths parasites, such as roundworm, flukes and tapeworm. Purge dewormers for use in livestock can be formulated as a feed supplement that is eaten, a paste or gel that is deposited at the back of the animal's mouth, a liquid drench given orally, an injectable, or as a pour-on which can be applied to the animal's topline. In dogs and cats, purge dewormers come in many forms including a granular form to be added to food, pill form, chew tablets, and liquid suspensions.

Oesophagostomum is a genus of parasitic nematodes (roundworms) of the family Strongylidae. These worms occur in Africa, Brazil, China, Indonesia and the Philippines. The majority of human infection with Oesophagostomum is localized to northern Togo and Ghana. Because the eggs may be indistinguishable from those of the hookworms, the species causing human helminthomas are rarely identified with accuracy. Oesophagostomum, especially O. bifurcum, are common parasites of livestock and animals like goats, pigs and non-human primates, although it seems that humans are increasingly becoming favorable hosts as well. The disease they cause, oesophagostomiasis, is known for the nodule formation it causes in the intestines of its infected hosts, which can lead to more serious problems such as dysentery. Although the routes of human infection have yet to be elucidated sufficiently, it is believed that transmission occurs through oral-fecal means, with infected humans unknowingly ingesting soil containing the infectious filariform larvae.

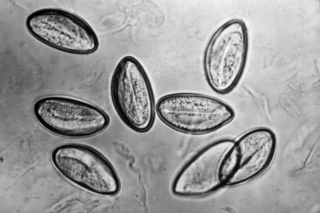

Pinworm infection, also known as enterobiasis, is a human parasitic disease caused by the pinworm, Enterobius vermicularis. The most common symptom is itching in the anal area. The period of time from swallowing eggs to the appearance of new eggs around the anus is 4 to 8 weeks. Some people who are infected do not have symptoms.

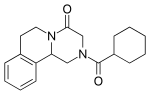

Anthelmintics or antihelminthics are a group of antiparasitic drugs that expel parasitic worms (helminths) and other internal parasites from the body by either stunning or killing them and without causing significant damage to the host. They may also be called vermifuges or vermicides. Anthelmintics are used to treat people who are infected by helminths, a condition called helminthiasis. These drugs are also used to treat infected animals, particularly small ruminants such as goats and sheep.

The effects of parasitic worms, or helminths, on the immune system is a recently emerging topic of study among immunologists and other biologists. Experiments have involved a wide range of parasites, diseases, and hosts. The effects on humans have been of special interest. The tendency of many parasitic worms to pacify the host's immune response allows them to mollify some diseases, while worsening others.

Soil-transmitted helminthiasis is a type of worm infection (helminthiasis) caused by different species of roundworms. It is caused specifically by those worms which are transmitted through soil contaminated with faecal matter and are therefore called soil-transmitted helminths. Three types of soil-transmitted helminthiasis can be distinguished: ascariasis, hookworm infection and whipworm infection. These three types of infection are therefore caused by the large roundworm A. lumbricoides, the hookworms Necator americanus or Ancylostoma duodenale and by the whipworm Trichuris trichiura.

Mass deworming, is one of the preventive chemotherapy tools, used to treat large numbers of people, particularly children, for worm infections notably soil-transmitted helminthiasis, and schistosomiasis in areas with a high prevalence of these conditions. It involves treating everyone – often all children who attend schools, using existing infrastructure to save money – rather than testing first and then only treating selectively. Serious side effects have not been reported when administering the medication to those without worms, and testing for the infection is many times more expensive than treating it. Therefore, for the same amount of money, mass deworming can treat more people more cost-effectively than selective deworming. Mass deworming is one example of mass drug administration.

Hookworms are intestinal, blood-feeding, parasitic roundworms that cause types of infection known as helminthiases. Hookworm infection is found in many parts of the world, and is common in areas with poor access to adequate water, sanitation, and hygiene. In humans, infections are caused by two main species of roundworm, belonging to the genera Ancylostoma and Necator. In other animals the main parasites are species of Ancylostoma. Hookworm is closely associated with poverty because it is most often found in impoverished areas, and its symptoms promote poverty through the educational and health effects it has on children. It is the leading cause of anemia and undernutrition in developing countries, while being one of the most commonly occurring diseases among poor people. Hookworm thrives in areas where rainfall is sufficient and keeps the soil from drying out, and where temperatures are higher, making rural, coastal areas prime conditions for the parasite to breed.

Gastropod-borne parasitic diseases (GPDs) are a group of infectious diseases that require a gastropod species to serve as an intermediate host for a parasitic organism that can infect humans upon ingesting the parasite or coming into contact with contaminated water sources. These diseases can cause a range of symptoms, from mild discomfort to severe, life-threatening conditions, with them being prevalent in many parts of the world, particularly in developing regions. Preventive measures such as proper sanitation and hygiene practices, avoiding contact with infected gastropods and cooking or boiling food properly can help to reduce the risk of these diseases.