Factitious disorder imposed on self, also known as Munchausen syndrome, is a factitious disorder in which those affected feign or induce disease, illness, injury, abuse, or psychological trauma to draw attention, sympathy, or reassurance to themselves. Munchausen syndrome fits within the subclass of factitious disorder with predominantly physical signs and symptoms, but patients also have a history of recurrent hospitalization, travelling, and dramatic, extremely improbable tales of their past experiences. The term Munchausen syndrome derives its name from the fictional character Baron Munchausen.

Hypochondriasis or hypochondria is a condition in which a person is excessively and unduly worried about having a serious illness. Hypochondria is an old concept whose meaning has repeatedly changed over its lifespan. It has been claimed that this debilitating condition results from an inaccurate perception of the condition of body or mind despite the absence of an actual medical diagnosis. An individual with hypochondriasis is known as a hypochondriac. Hypochondriacs become unduly alarmed about any physical or psychological symptoms they detect, no matter how minor the symptom may be, and are convinced that they have, or are about to be diagnosed with, a serious illness.

A thought disorder (TD) is a disturbance in cognition which affects language, thought and communication. Psychiatric and psychological glossaries in 2015 and 2017 identified thought disorders as encompassing poverty of ideas, neologisms, paralogia, word salad, and delusions - all disturbances of thought content and form. Two specific terms have been suggested — content thought disorder (CTD) and formal thought disorder (FTD). CTD has been defined as a thought disturbance characterized by multiple fragmented delusions, and the term thought disorder is often used to refer to an FTD: a disruption of the form of thought. Also known as disorganized thinking, FTD results in disorganized speech and is recognized as a major feature of schizophrenia and other psychoses. Disorganized speech leads to an inference of disorganized thought. Thought disorders include derailment, pressured speech, poverty of speech, tangentiality, verbigeration, and thought blocking. One of the first known cases of thought disorders, or specifically OCD as it is known today, was in 1691. John Moore, who was a bishop, had a speech in front of Queen Mary II, about "religious melancholy."

Malingering is the fabrication, feigning, or exaggeration of physical or psychological symptoms designed to achieve a desired outcome, such as relief from duty or work, avoiding arrest, receiving medication, and mitigating prison sentencing.

Somatization disorder was a mental and behavioral disorder characterized by recurring, multiple, and current, clinically significant complaints about somatic symptoms. It was recognized in the DSM-IV-TR classification system, but in the latest version DSM-5, it was combined with undifferentiated somatoform disorder to become somatic symptom disorder, a diagnosis which no longer requires a specific number of somatic symptoms. ICD-10, the latest version of the International Statistical Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems, still includes somatization syndrome.

Ganser syndrome is a rare dissociative disorder characterized by nonsensical or wrong answers to questions and other dissociative symptoms such as fugue, amnesia or conversion disorder, often with visual pseudohallucinations and a decreased state of consciousness. The syndrome has also been called nonsense syndrome, balderdash syndrome, syndrome of approximate answers, hysterical pseudodementia or prison psychosis.

Doctor shopping is the practice of visiting multiple physicians to obtain multiple prescriptions. It is a common practice of people with substance use disorders, suppliers of addictive substances, hypochondriacs or patients of factitious disorder and factitious disorder imposed on another. A doctor who, for a price, will write prescriptions without the formality of a medical exam or diagnosis is known as a "writer" or "writing doctor".

Psychogenic non-epileptic seizures (PNES), which have been more recently classified as functional seizures, are events resembling an epileptic seizure, but without the characteristic electrical discharges associated with epilepsy. PNES fall under the category of disorders known as functional neurological disorders (FND), also known as conversion disorders. These are typically treated by psychologists or psychiatrists. PNES has previously been called pseudoseizures, psychogenic seizures, and hysterical seizures, but these terms have fallen out of favor.

Pain disorder is chronic pain experienced by a patient in one or more areas, and is thought to be caused by psychological stress. The pain is often so severe that it disables the patient from proper functioning. Duration may be as short as a few days or as long as many years. The disorder may begin at any age, and occurs more frequently in girls than boys. This disorder often occurs after an accident, during an illness that has caused pain, or after withdrawing from use during drug addiction, which then takes on a 'life' of its own.

Pathological lying, also known as mythomania and pseudologia fantastica, is a chronic behavior characterized by the habitual or compulsive tendency to lie. It involves a pervasive pattern of intentionally making false statements with the aim of deceiving others, sometimes without a clear or apparent reason. Individuals who engage in pathological lying often claim to be unaware of the motivations behind their lies.

This glossary covers terms found in the psychiatric literature; the word origins are primarily Greek, but there are also Latin, French, German, and English terms. Many of these terms refer to expressions dating from the early days of psychiatry in Europe.

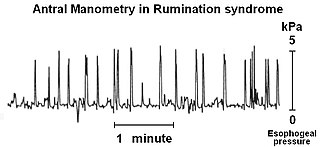

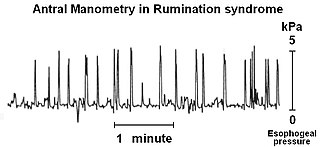

Rumination syndrome, or merycism, is a chronic motility disorder characterized by effortless regurgitation of most meals following consumption, due to the involuntary contraction of the muscles around the abdomen. There is no retching, nausea, heartburn, odour, or abdominal pain associated with the regurgitation as there is with typical vomiting, and the regurgitated food is undigested. The disorder has been historically documented as affecting only infants, young children, and people with cognitive disabilities . It is increasingly being diagnosed in a greater number of otherwise healthy adolescents and adults, though there is a lack of awareness of the condition by doctors, patients, and the general public.

Factitious disorder imposed on another (FDIA), also known as fabricated or induced illness by carers (FII), and first named as Munchausen syndrome by proxy (MSbP), is a mental health disorder in which a caregiver creates the appearance of health problems in another person, typically their child. This may include injuring the child or altering test samples. The caregiver then presents the person as being sick or injured. Permanent injury or death of the victim may occur as a result of their caregiver having the disorder. The behaviour occurs without a specific benefit to the caregiver.

Medically unexplained physical symptoms are symptoms for which a treating physician or other healthcare providers have found no medical cause, or whose cause remains contested. In its strictest sense, the term simply means that the cause for the symptoms is unknown or disputed—there is no scientific consensus. Not all medically unexplained symptoms are influenced by identifiable psychological factors. However, in practice, most physicians and authors who use the term consider that the symptoms most likely arise from psychological causes. Typically, the possibility that MUPS are caused by prescription drugs or other drugs is ignored. It is estimated that between 15% and 30% of all primary care consultations are for medically unexplained symptoms. A large Canadian community survey revealed that the most common medically unexplained symptoms are musculoskeletal pain, ear, nose, and throat symptoms, abdominal pain and gastrointestinal symptoms, fatigue, and dizziness. The term MUPS can also be used to refer to syndromes whose etiology remains contested, including chronic fatigue syndrome, fibromyalgia, multiple chemical sensitivity and Gulf War illness.

A functional symptom is a medical symptom with no known physical cause. In other words, there is no structural or pathologically defined disease to explain the symptom. The use of the term 'functional symptom' does not assume psychogenesis, only that the body is not functioning as expected. Functional symptoms are increasingly viewed within a framework in which 'biological, psychological, interpersonal and healthcare factors' should all be considered to be relevant for determining the aetiology and treatment plans.

Functional disorder is an umbrella term for a group of recognisable medical conditions which are due to changes to the functioning of the systems of the body rather than due to a disease affecting the structure of the body.

Somatic symptom disorder, also known as somatoform disorder, is defined by one or more chronic physical symptoms that coincide with excessive and maladaptive thoughts, emotions, and behaviors connected to those symptoms. The symptoms are not purposefully produced or feigned, and they may or may not coexist with a known medical ailment.

Loren Pankratz is a consultation psychologist at the Portland VA Medical Center and professor in the department of psychiatry at Oregon Health & Science University (OHSU).

The Structured Inventory of Malingered Symptomatology (SIMS) is a 75-item true-false questionnaire intended to measure malingering; that is, intentionally exaggerating or feigning psychiatric symptoms, cognitive impairment, or neurological disorders.