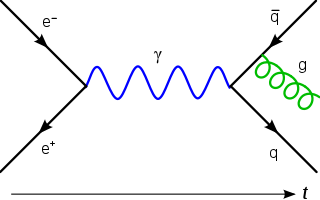

In particle physics, the electroweak interaction or electroweak force is the unified description of two of the four known fundamental interactions of nature: electromagnetism and the weak interaction. Although these two forces appear very different at everyday low energies, the theory models them as two different aspects of the same force. Above the unification energy, on the order of 246 GeV, they would merge into a single force. Thus, if the temperature is high enough – approximately 1015 K – then the electromagnetic force and weak force merge into a combined electroweak force. During the quark epoch (shortly after the Big Bang), the electroweak force split into the electromagnetic and weak force. It is thought that the required temperature of 1015 K has not been seen widely throughout the universe since before the quark epoch, and currently the highest human-made temperature in thermal equilibrium is around 5.5x1012 K (from the Large Hadron Collider).

In physics, the fundamental interactions or fundamental forces are the interactions that do not appear to be reducible to more basic interactions. There are four fundamental interactions known to exist:

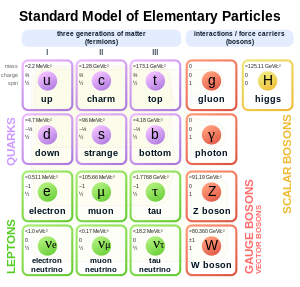

In particle physics, an elementary particle or fundamental particle is a subatomic particle that is not composed of other particles. Particles currently thought to be elementary include electrons, the fundamental fermions, as well as the fundamental bosons, which generally are force particles that mediate interactions among fermions. A particle containing two or more elementary particles is a composite particle.

In theories of quantum gravity, the graviton is the hypothetical quantum of gravity, an elementary particle that mediates the force of gravitational interaction. There is no complete quantum field theory of gravitons due to an outstanding mathematical problem with renormalization in general relativity. In string theory, believed by some to be a consistent theory of quantum gravity, the graviton is a massless state of a fundamental string.

In nuclear physics and particle physics, the weak interaction, which is also often called the weak force or weak nuclear force, is one of the four known fundamental interactions, with the others being electromagnetism, the strong interaction, and gravitation. It is the mechanism of interaction between subatomic particles that is responsible for the radioactive decay of atoms: The weak interaction participates in nuclear fission and nuclear fusion. The theory describing its behaviour and effects is sometimes called quantum flavourdynamics (QFD); however, the term QFD is rarely used, because the weak force is better understood by electroweak theory (EWT).

The Standard Model of particle physics is the theory describing three of the four known fundamental forces in the universe and classifying all known elementary particles. It was developed in stages throughout the latter half of the 20th century, through the work of many scientists worldwide, with the current formulation being finalized in the mid-1970s upon experimental confirmation of the existence of quarks. Since then, proof of the top quark (1995), the tau neutrino (2000), and the Higgs boson (2012) have added further credence to the Standard Model. In addition, the Standard Model has predicted various properties of weak neutral currents and the W and Z bosons with great accuracy.

Spontaneous symmetry breaking is a spontaneous process of symmetry breaking, by which a physical system in a symmetric state spontaneously ends up in an asymmetric state. In particular, it can describe systems where the equations of motion or the Lagrangian obey symmetries, but the lowest-energy vacuum solutions do not exhibit that same symmetry. When the system goes to one of those vacuum solutions, the symmetry is broken for perturbations around that vacuum even though the entire Lagrangian retains that symmetry.

In particle physics, the baryon number is a strictly conserved additive quantum number of a system. It is defined as

In particle physics, the W and Z bosons are vector bosons that are together known as the weak bosons or more generally as the intermediate vector bosons. These elementary particles mediate the weak interaction; the respective symbols are

W+

,

W−

, and

Z0

. The

W±

bosons have either a positive or negative electric charge of 1 elementary charge and are each other's antiparticles. The

Z0

boson is electrically neutral and is its own antiparticle. The three particles each have a spin of 1. The

W±

bosons have a magnetic moment, but the

Z0

has none. All three of these particles are very short-lived, with a half-life of about 3×10−25 s. Their experimental discovery was pivotal in establishing what is now called the Standard Model of particle physics.

In the Standard Model of particle physics, the Higgs mechanism is essential to explain the generation mechanism of the property "mass" for gauge bosons. Without the Higgs mechanism, all bosons (one of the two classes of particles, the other being fermions) would be considered massless, but measurements show that the W+, W−, and Z0 bosons actually have relatively large masses of around 80 GeV/c2. The Higgs field resolves this conundrum. The simplest description of the mechanism adds a quantum field (the Higgs field) which permeates all of space to the Standard Model. Below some extremely high temperature, the field causes spontaneous symmetry breaking during interactions. The breaking of symmetry triggers the Higgs mechanism, causing the bosons it interacts with to have mass. In the Standard Model, the phrase "Higgs mechanism" refers specifically to the generation of masses for the W±, and Z weak gauge bosons through electroweak symmetry breaking. The Large Hadron Collider at CERN announced results consistent with the Higgs particle on 14 March 2013, making it extremely likely that the field, or one like it, exists, and explaining how the Higgs mechanism takes place in nature. The view of the Higgs mechanism as involving spontaneous symmetry breaking of a gauge symmetry is technically incorrect since by Elitzur's theorem gauge symmetries can never be spontaneously broken. Rather, the Fröhlich–Morchio–Strocchi mechanism reformulates the Higgs mechanism in an entirely gauge invariant way, generally leading to the same results.

In mathematical physics, Yang–Mills theory is a gauge theory based on a special unitary group SU(n), or more generally any compact, reductive Lie algebra. Yang–Mills theory seeks to describe the behavior of elementary particles using these non-abelian Lie groups and is at the core of the unification of the electromagnetic force and weak forces (i.e. U(1) × SU(2)) as well as quantum chromodynamics, the theory of the strong force (based on SU(3)). Thus it forms the basis of our understanding of the Standard Model of particle physics.

A chiral phenomenon is one that is not identical to its mirror image. The spin of a particle may be used to define a handedness, or helicity, for that particle, which, in the case of a massless particle, is the same as chirality. A symmetry transformation between the two is called parity transformation. Invariance under parity transformation by a Dirac fermion is called chiral symmetry.

In the Standard Model of electroweak interactions of particle physics, the weak hypercharge is a quantum number relating the electric charge and the third component of weak isospin. It is frequently denoted and corresponds to the gauge symmetry U(1).

This article describes the mathematics of the Standard Model of particle physics, a gauge quantum field theory containing the internal symmetries of the unitary product group SU(3) × SU(2) × U(1). The theory is commonly viewed as describing the fundamental set of particles – the leptons, quarks, gauge bosons and the Higgs boson.

In particle physics, the history of quantum field theory starts with its creation by Paul Dirac, when he attempted to quantize the electromagnetic field in the late 1920s. Heisenberg was awarded the 1932 Nobel Prize in Physics "for the creation of quantum mechanics". Major advances in the theory were made in the 1940s and 1950s, leading to the introduction of renormalized quantum electrodynamics (QED). QED was so successful and accurately predictive that efforts were made to apply the same basic concepts for the other forces of nature. By the late 1970s, these efforts successfully utilized gauge theory in the strong nuclear force and weak nuclear force, producing the modern Standard Model of particle physics.

The J. J. Sakurai Prize for Theoretical Particle Physics, is presented by the American Physical Society at its annual April Meeting, and honors outstanding achievement in particle physics theory. The prize consists of a monetary award (US$10,000), a certificate citing the contributions recognized by the award, and a travel allowance for the recipient to attend the presentation. The award is endowed by the family and friends of particle physicist J. J. Sakurai. The prize has been awarded annually since 1985.

In physics, a charge is any of many different quantities, such as the electric charge in electromagnetism or the color charge in quantum chromodynamics. Charges correspond to the time-invariant generators of a symmetry group, and specifically, to the generators that commute with the Hamiltonian. Charges are often denoted by the letter Q, and so the invariance of the charge corresponds to the vanishing commutator , where H is the Hamiltonian. Thus, charges are associated with conserved quantum numbers; these are the eigenvalues q of the generator Q.

The Higgs boson, sometimes called the Higgs particle, is an elementary particle in the Standard Model of particle physics produced by the quantum excitation of the Higgs field, one of the fields in particle physics theory. In the Standard Model, the Higgs particle is a massive scalar boson with zero spin, even (positive) parity, no electric charge, and no colour charge that couples to mass. It is also very unstable, decaying into other particles almost immediately upon generation.

The 1964 PRL symmetry breaking papers were written by three teams who proposed related but different approaches to explain how mass could arise in local gauge theories. These three papers were written by: Robert Brout and François Englert; Peter Higgs; and Gerald Guralnik, C. Richard Hagen, and Tom Kibble (GHK). They are credited with the theory of the Higgs mechanism and the prediction of the Higgs field and Higgs boson. Together, these provide a theoretical means by which Goldstone's theorem can be avoided. They show how gauge bosons can acquire non-zero masses as a result of spontaneous symmetry breaking within gauge invariant models of the universe.